Store

The compositions on this recording span nearly fifty years — from Op. 1 (1953), Op. 7 (1960), and Op. 22 (1968), through Op. 43 (2001).

They exhibit a wide variety of styles. It is interesting to reflect for a moment on the stylistic evolutions of other composers. Some find a particular style early on and maintain it throughout their lives – a category that includes Johannes Brahms and Frédéric Chopin. Others gradually evolve from one style to another that is totally different, usually going from conservative to radical. Alexander Scriabin and Elliott Carter are examples. Finally, there are composers who write in a variety of styles, some of which are surprisingly different in nature — Béla Bartók and Igor Stravinsky immediately come to mind. I believe I fall into this latter category. At present, I feel comfortable writing in just about any idiom; and when a new work is requested, I ask what style is desired….

….Participating as a pianist in this recording, and thus gaining an overview of my compositions, has been a revealing experience. It was also enlightening to have had the opportunity to collaborate with Mr. Pikler and Mr. Stucka, who are both fine musicians and dedicated perfectionists.

— Easley Blackwood

Preview Excerpts

EASLEY BLACKWOOD (b. 1933)

Second Viola Sonata, Op. 43*

First Violin Sonata, Op. 7

Piano Trio, Op. 22

First Viola Sonata, Op. 1

Artists

1: Charlie Pikler, viola

6: Charlie Pikler, violin

Program Notes

Download Album BookletEasley Blackwood Chamber Music

Notes by Easley Blackwood

The compositions on this recording span nearly fifty years — from Op. 1(1953), Op.7 (1960), and Op. 22 (1968), through Op. 43 (2001). They exhibit a wide variety of styles.

It is interesting to reflect for a moment on the stylistic evolutions of other composers. Some find a particular style early on and maintain it throughout their lives — a category that includes Johannes Brahms and Frédéric Chopin. Others gradually evolve from one style to another that is totally different, usually going from conservative to radical. Alexander Scriabin and Elliott Carter are examples. Finally, there are composers who write in a variety of styles, some of which are surprisingly different in nature — Béla Bartók and Igor Stravinsky immediately come to mind. I believe I fall into this latter category. At present, I feel comfortable writing in just about any idiom; and when a new work is requested, I ask what style is desired.

The style of my Op. 43 (Second Viola Sonata) is distinctly conservative, especially when compared with stylistic trends over the past forty years. This work was commissioned by Prof. Ivan Sellin, a physicist who is also an accomplished violinist-violist. Prof. Sellin requested a composition that would suggest the idiom of Bartók, as in the Contrasts for Violin, Clarinet, and Piano, or of Prokofieff, as in the Overture on Hebrew Themes, and I was glad to oblige.

The five movements exhibit an unusual key scheme: the first is in C-sharp minor; the second is in D major; the third is in E flat minor; and the fourth is in E major. Thus far, the tonics make an ascending chromatic scale. The fifth movement is once again in C-sharp minor, which makes a smooth modulation from the E-major triad at the close of the fourth movement.

The first movement is a sonata rondo — unusual in that the tempo is very leisurely. For the most part, keys are readily identifiable, although there is a section in the development that verges on atonality. The second movement is also a sonata rondo, but in a more conventional style, having a scherzo-like character. Once again, there is a section in the development that is largely atonal, although the final cadence is unmistakably in D major.

The third movement is a scherzo with trio. The rhythmic arrangement of the scherzo sections is very unusual, being for the most part in 13/8 time. Prof. Sellin has always been intrigued by the section of Bartók’s Contrasts in the same meter, and requested that a portion of the Sonata should also be in 13/8 time. The more conventional trio section provides a sharp contrast. The fourth movement is a free fantasy, with fairly lengthy passages for the viola alone. The final movement is a sonata form, with new material being introduced in the development. This is recalled near the end; and the coda, with its sudden change in tempo and rhythmic modality, closes the movement in an unexpected way

The melodic contours of Op. 7 (First Violin Sonata) show the influence of Paul Hindemith, but the harmonic language is rather more like the pre-serial atonal works of Arnold Schönberg — an interesting combination, considering that those composers held each other’s music in low regard. The first movement is a sonata form in which the first and second themes are presented in reverse order in the recapitulation. The second movement is a sonata without development. At the very end, the closing bars of the first theme are heard once again. The last movement is a sonata rondo in which the repeating material is sometimes presented exactly, and sometimes in a variety of variations. The slow, meditative coda is unlike anything else in the movement, and makes a surprise ending.

Op. 22 (Trio for Violin, Cello, and Piano) is in an atonal, polyrhythmic idiom that was pioneered in Darmstadt during the 1960s. Its style most nearly resembles both Elliott Carter and Charles Ives. Although largely atonal, the harmonic idiom is not merely random dissonance, in which notes and sonorities are chosen so as to bring about the maximum possible surprise. On the contrary, there is a constant sense of harmonic resolution from one sonority to the next. The first movement is a sonata without development, followed by a brief coda. The two themes are distinguished by differences in rhythmic modality: the first is freely flowing without a distinguishable pulse, while the second is characterized by successions of evenly spaced notes — mainly sixteenths and septuplet sixteenths, occasionally quintuplets. The second movement is a scherzo and trio. The scherzo is in a syncopated, dancing rhythm; the trio is quiet and meditative. The repeat of the scherzo is curtailed, and considerably slower than the initial statement. The last movement is a sonata form, preceded by a free, slow introduction that is divided into two distinct parts, separated by a brief episode played by the piano alone. There are tonal elements in the second part: a chromatic, modal arrangement of D-flat major, followed by A minor, and then a return to D-flat major. The two themes of the body of the movement feature the polyrhythm three-against-five, often with syncopations in both cross rhythms. There is much dialogue between the piano and the string duo. The central portion of the development consists of a rhythmic variation of the second section of the slow introduction. Near the end, elements of the slow introduction return, and the movement closes with a brief coda that recalls the second theme.

Op. 1 (First Viola Sonata) is in a style that resembles Alban Berg and Olivier Messiaen. For six weeks in 1949, I studied with Messiaen at the Berkshire Music Center and found him to be a fine musician with a persuasive intellect. When I wrote Op. 1, I was studying with Hindemith at the Yale School of Music. He thoroughly disliked the piece, declaring that its style was “unnatural.” I argued back that all musical styles are basically unnatural, save perhaps for pentatonic monody. Hindemith was not a skilled debater.

Formally, the first movement of Op. 1 is a sonata without development, preceded by a slow introduction. The first theme is largely atonal, but the second theme contains more nearly tonal elements. As an unusual feature, the return of the second theme in the recapitulation is in the same key (A-flat major) as in the exposition, although greatly changed in character. The second movement begins with a quick introduction that is abruptly broken off. This is followed by a set of variations whose theme is drawn from the first movement’s introduction, which is repeated exactly at the end of the fourth variation. The last movement also begins with an introduction, this one a fragment of the first movement’s second theme. The main body of the movement is a sonata form whose development is a palindrome based on the second movement’s introduction. Near the end, there is a brief recall of the introduction of the first movement, but in a different rhythmic arrangement.

Participating as a pianist in this recording, and thus gaining an overview of my compositions, has been a revealing experience. It was also enlightening to have had the opportunity to collaborate with Mr. Pikler and Mr. Stucka, who are both fine musicians and dedicated perfectionists.

Album Details

Total Time: 71:48

Producers: Easley Blackwood, James Ginsburg

Engineer: Bill Maylone

Graphic Design: Melanie Germond

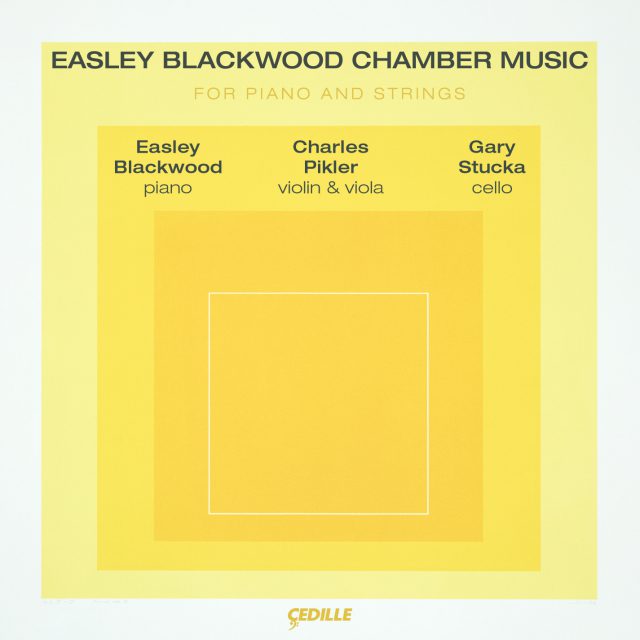

Cover: White Line Square I, published 1966 by Josef Albers © 2005 The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Recorded: February 2-3 (Op. 43), April 28 (Op. 1), and September 4 (Op. 7), 2002; and December 4, 2004 (Op. 22) at WFMT Chicago

Piano Technician: Ken Orgel

Publishers:

First Viola Sonata, Op. 1 © 1959 Theodore Presser

First Violin Sonata, Op. 7 © 1961 Easley Blackwood

Piano Trio, Op. 22 © 1968 Easley Blackwood

Second Viola Sonata, Op. 43 © 2001 Easley Blackwood

Release date: April 2005

© 2005 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 081