Store

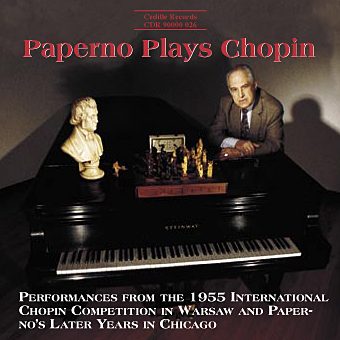

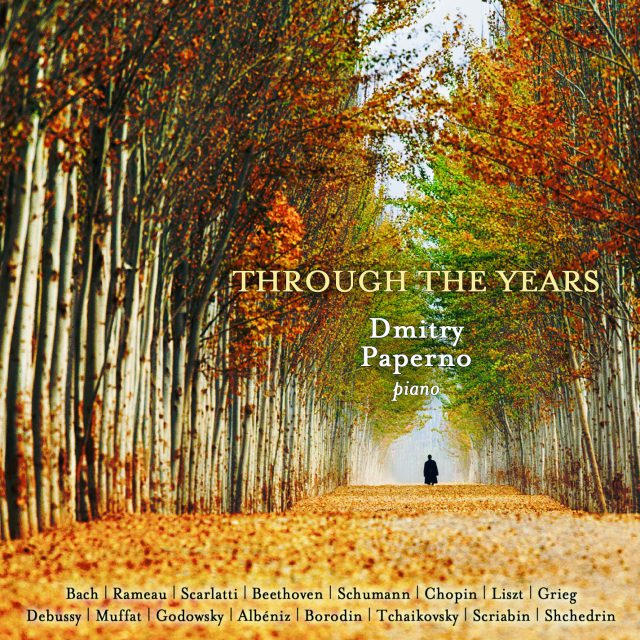

Dmitry Paperno, a major Soviet-era pianist, is heard on a valedictory recording released in honor of his seventy-fifth birthday. Through the Years, Paperno’s seventh CD for Cedille Records, is a 2001 studio recording comprising 17 familiar and less-familiar pieces from the Baroque era to the mid-twentieth century.

Through the Years refers not only to the broad swath of music history represented on the program but also to the timeline of Paperno’s career. Paperno, who emigrated to the U.S. in 1976, says he had been playing the Scarlatti, Beethoven, and Scriabin pieces since his days in the Soviet Union. Many pieces on the new CD entered his repertoire late in his career, during the decade leading up to the recording. Paperno says he is particularly pleased to share the lesser-known works on the CD, such as the Grieg an Rameau, and the piano transcriptions, which he calls “pearls and gems.”

Preview Excerpts

JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH (1685-1750)

JEAN PHILIPPE RAMEAU (1683-1764)

DOMENICO SCARLATTI (1685-1757)

LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN (1770-1827)

ROBERT SCHUMANN (1810-1856)

FREDERIC CHOPIN (1810-1849) / FRANZ LISZT (1811-1886)

FRANZ LISZT

EDVARD GRIEG (1843-1907)

CLAUDE DEBUSSY (1862-1918)

GOTTLIEB MUFFAT (1690-1770) / BELA BARTOK (1881-1945)

JEAN-PHILIPPE RAMEAU / LEOPOLD GODOWSKY (1870-1938)

ISAAC ALBENIZ (1860-1909) / LEOPOLD GODOWSKY

ALEXANDER BORODIN (1833-1887)

PETER TCHAIKOVSKY (1840-1893)

ALEXANDER SCRIABIN (1872-1915)

Two Poems, Op. 32

RODION SHCHEDRIN (b. 1932)

from French Suite No. 5 in G major, BWV 816 (c.1722)

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletThrough the Years

Notes by Raymond Tipper

[1] Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750)

Sinfonia No. 2 in C Minor

In 1723, Bach decided to publish 30 short clavier works he had written for pedagogical purposes. This collection of Inventions — 15 in two parts and 15 in three (which Bach called Sinfonias) — formed an important part of his amazing progressive school of polyphony, from the simplest exercises (“Notebooks of Anna Magdalena”) to the highest degree of sophistication (“Well Tempered Clavier”). A collection of fuguettos or, in some cases, outright fugues, the Sinfonias are notable for their polyphonic inventiveness and wide range of emotions.

The Second Sinfonia in C minor is an intimate, slightly melancholic meditation, full of calm and dignity. As always, the clarity of the three conversing voices is unsurpassed. It offers an example of how close to sonata form Bach’s structures often came: there are two thematic motives, a short development section, and an appropriate tonal plan. The final return to C minor allows the “second subject” to frame this small gem beautifully in an almost elegiac mood.

[2] Jean Philippe Rameau (1683–1764)

Le Rappel des Oiseaux

Speaking of melancholy, this refined and delicate kind of sadness is much more typical for French Baroque composers. Along with Francois Couperin “the Great” (1668–1733), Rameau was the most outstanding representative of this style, often called Rococo. Rameau’s “Bird calls,” Couperin’s “La Couperin,” the famous “Coucou” by Daquin, and so many other animated French harpsichord miniatures share a touch of this subtle sadness, as well as the frequent use of the key of E minor. More than mere coincidence, these similarities appear to be something of a common stylistic bond among the French contemporaries of J.S. Bach, Handel, Scarlatti, and Purcell.

[3] Domenico Scarlatti (1685–1757)

Sonata in C minor (L. 352)

Many of the “sonatas” (music to be played, not sung) of the pre-classical era were really suites — or collections of small pieces, often of a dance character. Scarlatti initiated a major turning point in the history of music when he wrote several hundred clavier miniatures modestly titled Essercizi. This is how music’s most ingenious design — sonata form — was born in its elementary conception. Sonatas such as this one established the principle of two musical characters, a short development section with some tonal deviations, and a return of the initial material, not necessary verbatim but, most important, with a certain correlations of keys. It took many decades and figures like C.P.E. Bach and Haydn to bring sonata form to its triumphant peak as one of the most dominant musical forms. In addition to their amazing creative content, Scarlatti’s sonatas are full of technical demands for performers, including wide jumps, double notes such as thirds, and fast repeated notes. All of Scarlatti’s virtuosic innovations became staples for the outstanding piano composers of later generations such as Clementi, Mendelssohn, and Liszt.

Mr. Paperno offers his own personal tribute here:

The name Scarlatti will always be mentioned with deepest admiration and gratitude for his immortal music embracing all human feelings and for his “discovery” of indestructible logic and flexibility of sonata form. Let us also not forget that by the rarest, triple coincidence, Scarlatti was born in the “Year of Geniuses” — 1685 — with Bach and Handel….

[4] Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827)

Andante Favori, 1804

Beethoven originally intended this piece as the second movement for his “Waldstein” Sonata, opus 53. Probably due to the length of the sonata’s monumental opening Allegro and final Rondo, Beethoven decided to replace the Andante with a short, dark and meditative Adagio. The withdrawn movement was published separately under the current title, with no opus indication. It is a beautifully developed Rondo, full of kindness, simplicity, and wisdom.

[5] Robert Schumann (1810–1856)

Intermezzo in D minor, Op. 4, No. 5 (1832)

The most refined and intimate piece from Schumann’s opus 4, this Intermezzo is usually performed without a break after piece No. 4. The young composer wrote in his diary: “All my heart is contained in you, my dear fifth intermezzo. This music is like something between speech and thought.” Schumann’s main theme, with its palpitating purity, is truly an inspired “find.” The intermediate episodes, both dramatic and lyrical, supercede each other through persistent tonal modulations and a very animated polyphonic texture of subordinate voices. There is no room for hesitation in the last lines, though — Schumann ends the Intermezzo in a strong, decisive mode.

[6] Frederic Chopin (1810–1849)

Song: “Moja Pieszcotka” (“My Darling”) Op. 74, No. 12 (1837, published 1855)

Piano transcription by Liszt from Six Polish Songs (1855, published 1860)

Singers usually perform this charming piece in the dance style of a mazurka. Liszt, however, emphasized the song’s lyrical nature in his transcription and even subtitled it “Nocturne.” Chopin’s poetry and Liszt’s openness and virtuosity (including four small cadenzas) are blended here in a seamless manner. After a passionate, “Lisztian” culmination, the intimate opening returns with its amazing “Chopinesque” shifts in harmony, beautifully framing this poetic gem.

[7] Franz Liszt (1811–1886)

Sonetto No. 104 by Petrarca in E major

No. 5 from “Annés de Pelerinage,” second year, “Italy” (1838–39, re-edited in 1846)

Following the text of Petrarch’s sonnet, an agitated, gusty opening gives way to the calm beginning of a concentrated love story. The subsequent mood continually shifts from lyrical to explosions of passion in Liszt’s characteristically theatrical manner. After a powerful, virtuosic culmination — fortissimo with octaves, double notes, and long trills — the music gradually subsides into a heavenly Coda. Liszt’s harmonic creativity (juxtaposition of remote keys, smoothly executed modulations, the always-fresh use of augmented chords, etc.) is here revealed at its fullest extent.

[8] Edvard Grieg (1843–1907)

“From Early Years”

Lyric Pieces (1867–1891), Op. 65, No. 1

Grieg worked on his Lyric Pieces — a collection of 66 miniatures in ten books — off and on for 38 years. As a result, we have a kind of encyclopedia of romantic Norwegian music with its rich “Northern” harmonies, folk-inspired melodies, and sincere poetic feelings. As always, Grieg’s musical language is distinctive and recognizable. Along with Chopin, Dvorak, and members of the Russian school, Grieg was one of the 19th century’s most nationalistic composers. At the same time, like Mozart, Schubert, and his beloved idol Schumann, Grieg was a champion of kindness in music (as well as in life), a quality that immediately touches every listener. In the Lyric Pieces in general, and From Early Years in particular, all of these Grieg qualities are clearly reflected. It is one of the most developed pieces — in both length and texture — of the whole collection, written toward the end of Grieg’s creative life. It is a reminiscence, with drama, joy (a folk-dance scene, like a mirage from bygone years), and sadness, all full of dignity. All told, it creates an impressive image of a sensitive man of unique talent and strong feelings.

[9] Claude Debussy (1862–1918)

Images, Book 1, No. 2 (1905) “Hommage a Rameau”

A founder and genius of French impressionist music, Debussy applies all his gift for creating ineffable harmonies and colors to express his love and admiration for his great predecessor of 200 years earlier, Jean Baptiste Rameau. The circle of images Debussy conjures here is quite diverse: a thoughtful opening mood; a mysterious procession in the background of low ostinato bells; a middle section comprising new thematic material with “never-resolved” harmonies; a gradual, in several waves, animation of dynamics, pace, and texture that bursts into a powerful culmination — one can visualize dozens of shining trumpets raised up in the air — and a calming down that restores the familiar key and images of the opening. The last lines (Coda) — a lucid succession of plain major and minor chords — finally establishes the G-sharp-minor key as the music descends slowly back into the past.

[10] Muffat Gottlieb (1690–1770) / Bela Bartok (1881–1945)

Fugue in G minor

In 1926 and 1927, Bartok premiered his ten piano transcriptions of pre-Bach clavier pieces, all by Italian composers, or so he thought. About 50 years later, however, a few curious musicians with an amazing understanding of early keyboard styles were able to discover and prove a very intriguing case of misattribution. I refer the reader to a short but brilliant essay by Susan Wollenberg: “A Note on Three Fugues Attributed to Frescobaldi” from The Musical Times (1975, p. 133). Musicians unfamiliar with this detective story remain unaware that the true author of this masterful, deep fugue in G minor was not Girolamo Frescobaldi (1583–1643), the composer and legendary organist of St. Pietro in Rome for 35 years (to whom the piece was misattributed), but rather the Austrian composer Gottlieb Muffat.[1] With its exemplary handling of three- and four-voice counterpoint and its constant harmonic and rhythmic flow, this music speaks in an intimate and touching manner that listeners cannot fail to appreciate.

In the mid-1920s, Bartok turned to transcribing Baroque music as a way to develop further his own piano style and extend his concert repertoire. As a genius composer and, in this instance, co-author, Bartok projected his own pianistic personality onto little-known clavier music of two centuries earlier. Bartok adapted the fugue into a more open concert piece with gradually increasing dynamics, up to triple-forte toward the end, and heavier, organ-like textures (octaves and chords). In his interpretation, however, Mr. Paperno chooses to conclude the piece as it begins, by pulling back at the very end and returning to Muffat’s simpler keyboard textures and more serene dynamics.

[11] Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683-1764) / Leopold Godowsky (1870–1938)

Elegy (Deux Gigues)

One of the most outstanding pianists of his generation, Godowsky also made his mark on history with his numerous, brilliantly creative transcriptions of keyboard music of different eras and styles from the 18th century, to his 53 Exercises (of the highest possible degree of difficulty) after Chopin Etudes, to Strauss Waltzes, to contemporaneous Spanish music. The E-minor Elegy offers an example of Godowsky’s deep musical insight: he somehow managed to find and bring out the lyricism and melancholy within these two fast and active Rameau “Gigues en Rondeaus.” Note how Godowsky’s transcription holds to the previously mentioned tendencies in Rococo clavier music: a subtle sadness and the key of E minor. The attentive listener will appreciate Elegy’s rich contrapuntal texture and numerous imitations, in all independent voices. Mr. Paperno believes the first two bars of Godowsky’s Coda deserve to be repeated, and does so on this recording.

[12] Isaac Albeniz (1860–1909) / Leopold Godowsky

Tango, from Suite España, op. 165, No. 2

In the 1930s, this transcription was one of the most popular encores on concert stages throughout the world. The passionate and languid tango originated in the 19th century as a solo female dance in South and Central America (Argentina and Cuba). Later, it became popular in European ballrooms. It would not be unreasonable to suggest that Albeniz had in mind the old Cuban-Spanish tango with its capricious images and movements and elusive seductiveness when he composed this charming piece. Godowsky’s version accentuates these aspects of Albeniz’s conception in the most tactful way. Over the background of a common Habanera 2/4 meter, he diversifies the rhythm of the tango by using combinations of duplets and triplets (two notes against three) and intensifies the piano texture by making the piece polyphonic, with several refreshing imitations and canons. In his interpretation, Paperno adds a little harmonic “spice” by adding some subordinate voices before the recapitulation. Paperno also chooses to repeat three bars near the end.

[13] Alexander Borodin (1833–1887)

“In a Monastery,” No. 1 from Petite Suite

“The Little Suite” is Borodin’s only composition for piano. Rarely performed outside of Russia, this music deserves a better fate. “In a Monastery” combines the persistent chime of a small Russian village church with a folk tune displaying characteristic Russian “light sadness,” reflecting the way young peasant women used to sing in three or four voices after a day of hard work. The song approaches closer and closer and, through a long-building crescendo, blends with the bells, now powerfully ringing at full-swing, bringing the piece to a dramatic emotional culmination. After a long pause, like one catching his breath, the remote tune returns, remaining pianissimo, and then is replaced by the opening chime — a relatively rare mid-19th century example of a mirror-type form. Eventually, the last low bell tone dissolves into the evening air.

[14] Peter Tchaikovsky (1840–1893)

“Dialogue,” op. 72, no. 8 (1893)

Tchaikovsky’s final piano opus contains 18 pieces. Since he wrote it in the year of his death, each of these miniatures might, in theory, be his last piano work. The piece’s title speaks for itself: this is an unpretentious salon piece, typical for the home music-making that went on in 19th-century Russian gentry estates. The piece suggests the innocent and intimate conversation of a couple in love. An animated middle section with more complicated textures and frequent harmonic changes brings both voices together in a rapturous culmination. The Coda is one of Tchaikovsky’s trademark calming downs with a succession of descending two-note sighs (cf., Romeo and Juliet). As the music melts away, it leaves an indelible impression of this bittersweet scene from a bygone era in “good old Russia.”

[15–16] Alexander Scriabin (1872–1915)

Two Poems, opus 32 (1903)

A gem of Scriabin’s middle period, the Two Poems are clearly tonal, but contain more moments of harmonic uncertainty than tonic resolutions. These pieces demonstrate the two contrasting sides of Scriabin’s musical personality — a fragile, pure lyricism and the ecstatic power of the victorious human spirit. The first Poem, in F-sharp major, is amazing in its refined, “unearthly” harmonization and Scriabin’s masterful use of his unique kind of counterpoint (which is always present in his three-and-more-voice piano textures). The second section, marked pianissimo, adds to the beauty with its shifting of different rhythmical designs in both hands (five against three). At the beginning of the recapitulation, the two conversing voices switch places in such a natural way that they sound like fresh musical material. The very impetuous second Poem, in D major, is the complete opposite of the first. Despite its concise form, the music develops dramatically toward a triumphant third fortissimo appearance of the opening trumpet-filled “tutti” — so powerful that the calming-down measures that follow sound like the inevitable rest that comes after full exhaustion.

[17] Rodion Shchedrin (b. 1932)

Humoresque (1962)

This piece is a rare example of a musical “Humoresque” that can actually make you laugh, or at least smile. In it, the young Shchedrin offers an unflattering portrait of middle-class “Homo Sovieticus” — a person who tries to look important, “cultured,” and polite, but who can’t avoid revealing himself as an inebriated lout. The piece sounds like a dialogue among something like a tuba and three flutes which, after several unsuccessful attempts and irresolute stops, ends drastically with a short outburst of rage — a triple-forte chord in the totally unexpected key of E-flat major (a depiction of Russian cursing?).

[18] Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750)

Sarabande from French Suite No. 5 in G Major

An ancient Spanish dance, the sarabande, made its way to central Europe in the 17th century as a slow, stately minuet-type dance for couples and sometimes as an opening procession in theaters and at court balls. As a musical form, the sarabande became one of the four “obligatory” dances in Baroque suites. Bach’s sarabandes transcend the specifics of the genre with their humanity, depth, and beautiful simplicity. Those composed in major keys, such as this one in G major, produce an especially spiritual impression: they discourse on the eternal problems of human life and death with a wise calmness and confidence inspired by faith. It may be compared with the immortal Aria from The Goldberg Variations, with which it shares the same genre, key, and a similar tonal plan. What makes the two pieces truly comparable, however, is the rare sense of peace that both impart to the listener.

Album Details

Total Time: 74:47

Produced by Dmitry Paperno and James Ginsburg

Engineer: Bill Maylone

Recorded: May 1 & 2, 2001 at WFMT, Chicago

Graphic Design: Melanie Germond

Cover Photo: Art Wolfe © The Image Bank

Microphones: Sennheiser MKH 40, Schoeps MK 21

© 2004 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 074