Store

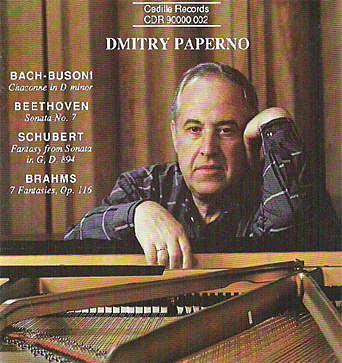

Pianist Dmitry Paperno’s second recording on Cedille Records embraces four periods in the development of German music, with works of Bach-Busoni, Beethoven, Schubert, and Brahms.

The unusual liner notes for this stimulating program take the form of a Q&A interview between Paperno and producer James Ginsburg that elicits insightful commentary about each piece and the program’s overall concept.

Paperno describes Busoni’s transcription of Bach’s Chaconne as “religious in its insight and grandeur, without being sacred.” He finds Beethoven’s early Piano Sonata No. 7 “so varied, so full of different impressions of life,” considering Beethoven’s youth at the time.

Paperno first took a performing interest in Schubert’s Fantasy when he heard it on a TV commercial(!). Brahms’ 7 Fantasies, Op. 116, are “philosophy in sound — music made for forever,” Paperno says.

Preview Excerpts

J.S. BACH (1685-1750) / tr. Busoni

LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN (1770-1827)

Sonata No. 7 in D, Op. 10, No. 3

FRANZ SCHUBERT (1797-1828)

JOHANNES BRAHMS (1833-1897)

Seven Fantasies, Op. 116

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletAn interview with Dmitry Paperno

Notes by James Ginsburg

JG: When did you start playing the Bach-Busoni Chaconne?

DP: I believe it was during my second year at the Moscow Conservatory — in 1947 or ’48. This has always been a very special piece for me. My teacher, Alexander Goldenweiser, was relatively cool about transcriptions, but he called the Chaconne a congenial piece, meaning that the transcription was, for him, equal to the original.

JG: How do you feel about transcriptions?

DP: One must remember that for a long time piano transcriptions of symphonies, songs, operas (“paraphrases”), all types of music, were widely used for educational purposes and served to bring music to small towns, as Liszt did with Beethoven’s symphonies, for instance. And I still like transcriptions: there should be no arrogance toward the genre (of course, some transcriptions are more creative than others). As the best possible examples of the genre I would name Liszt’s Rigoletto and Don Giovanni. But when it comes to Bach, Busoni may be the top transcriber.

JG: Busoni’s Bach transcriptions tend to be derived from organ pieces and, consequently, display intensive piano textures. The Chaconne is unusual in that Busoni created a big virtuoso piano piece out of a work for solo violin [the last movement of Bach’s Violin Partita No. 2 in D minor, BWV 1004].

DP: The Chaconne is a great concert piece for piano. Yet Busoni managed to save the spirit of the violin as well as organ — without which sound there is no Bach-Busoni as such.

JG: There is one episode toward the end of the Chaconne you refer to as “Christ’s Tears.” Does this relate specifically to Busoni’s transcription or to Bach’s original as well?

DP: It is, of course, part of the original Bach piece; but it is the specific timbre of the keyboard that made me notice this quality in the slow drops in the very sad D minor beginning of the last third of the piece.

JG: Is this theological analogy a reference or an original observation?

DP: No, this is purely my own subjective feeling. And, more than that, I would say that this piece is, as a whole, an amazing, beautiful representation of religious music without being sacred, but religious in its insight and grandeur.

JG: It seems particularly striking that in one section of this piano transcription of a solo violin piece Busoni penned the unusual indication, “Quasi tromboni” [like trombones].

DP: Yes. This is an example of Busoni’s great imagination and fantasy in his ability to find the timbres of each instrument in his writing. This was also true of his playing. Busoni’s own recordings are absolute knockouts technically, full of principles of his you may not accept or even like; but you have to, nonetheless, appreciate his inexhaustible creativity and powerful personality (I would compare him in this way with Glenn Gould). In general, the Chaconne is a great example of the transcription of Bach’s music, maybe the best.

JG: Moving on to the Beethoven: when did you first play this piece?

DP: It was even earlier . . . during the war; I believe it was in 1944, when I was 15. My performance at that time really was that of a youngster. I played it for Moscow Radio about ten years later and grew to dislike that performance enough that I asked them not to play the tape again.

JG: How has your interpretation changed since then?

DP: It’s a matter of pace and tempo. As I get older, I am continually amazed by the general tendency to play slower than 20, 30, not to mention 50 years ago. And I often don’t like some of my own earlier recordings because of that — not because I was worse than others — the ability to play fast was, at that time, considered a virtue. Take Toscanini. Or, for pianists, Schnabel or Cortot. Now their performances sound to me almost constantly hectic and in a hurry, almost obsolete nowadays (sorry!). (The only exception to this trend was Rachmaninov, due to the mighty human personality he projected even beyond his incredibly virtuosic playing.) I don’t know if it was an influence of the war, the terrible time humanity came through, but if Art is a reflection of our material life, something happened that makes us wish to find some island of refuge from the aggressiveness and pushiness of the everyday world. And it’s still happening in music. If you take the later recordings of Gilels or Ashkenazy, some of them can sound almost artificially slow — not because they’re trying to be “original,” but because that has become the language of musical communication today.

JG: Pacing becomes an interesting question in this sonata since the first movement is marked Presto while the second is a Largo. How can one realize that contrast without overdoing things?

DP: We have to remember that any author’s indication — of tempo in this case — can be, and is defined differently as it goes through the performer’s personality. For me, the key to the first movement is to unify the pace of the whole movement. The numerous fermatas simply emphasize that each succeeding section should be a continuation of the previous pace of “Presto” (how fast is “Presto,” is up to you).

JG: Another way Beethoven seems to promote stediness in this Presto is by ending eighth note runs “slower,” with a triplet of quarter notes.

DP: Beethoven’s scores are filled with such indications (the fourth and fifth piano concertos, for example). And, instead of being grateful and feeling blessed for having these remarks, we often ignore them. When Klemperer came to Moscow in the late 1920s to conduct all nine Beethoven symphonies he insisted on 25 rehearsals, which greatly upset the musical bureaucrats who felt the musicians “knew” the symphonies by heart already. During one rehearsal, Klemperer, who was a disagreeable man, noticed someone sitting in the hall taking notes. The conductor demanded, “What are you doing here?” The man said, “Maestro, I am writing down your priceless remarks.” Klemperer responded, “Close your notebook, go home, and open Beethoven’s scores: it’s all in there.”

JG: I know you consider the Seventh Sonata a precocious piece for the young Beethoven. What in particular do you find innovative?

DP: First of all, the “amazing depth of melancholy” in the Largo, to borrow the great French writer, Romain Rolland’s phrase. Full of moments of pressure, tragedy, begging, despair — for example, the end of the F major section leading into the recapitulation — it’s very gloomy, hopeless music. We never had music for piano like it before. Second, of course, the musical language of the Rondo [last movement].

JG: While the first two movements of the Seventh Sonata are well appreciated, the virtues of the third and especially the fourth movement may be overlooked. What strikes me about both movements is their humor —

DP: Yes, but the way the third movement starts — it’s coming back to life after it sounded as if everything was over. There isn’t even any protest at the end of the Largo. And then, in the most simple, childlike way, he starts the Minuet in D major — like a window opening and letting in the next day’s sun.

JG: Beethoven’s humor does come out later as he interrupts the most graceful of Minuets with a Trio that sounds almost like an elephant dancing.

DP: Sure. After he has come back to life, we get the sun, and the beauty of nature, and also humor — without which Beethoven himself maybe would not have survived.

JG: The Rondo has its own brand of humor with its constant stopping and starting —

DP: The fourth movement is very special for me. I have always loved it; and I think this movement has been a little underestimated. It’s so diverse and, at the same time, so extremely natural. Especially when you think back on the tragic tension of the second movement, this is an extremely human ending to one of the greatest sonatas of Beethoven’s early period.

JG: The conclusion is especially striking as first you have a series of chords welling up almost like Schubert, and then, suddenly, he ends the piece with a simple, scale-like passage of sixteenth notes — almost a trick ending.

DP: Flying away. . . . It’s so varied, so full of different impressions of life, such extremely kind music. And this impresses me no less than the slow movement: for such a relatively young man to be already so mature, observing, and wise.

JG: To continue on to the Schubert; again, when did you first take up this piece?

DP: This is one of my not-too-many new pieces in this country. And it started in a funny way. I had heard this music maybe two or three times in my life — the sonata is rarely played on stage because of its length. It never occurred to me that I could play it; I played some Schubert early in my career, but Schubert is not a composer for youngsters. And then, several years ago, I saw a TV commercial for some perfume (!), and the music in the background just struck me — I was charmed by its beauty. The only thing I recognized was that it was Schubert. I looked through my music, found it in the G major Sonata, and decided I had to learn it.

JG: When you speak of the “G major Sonata,” we should make it clear that this was originally four separate pieces which were later published together as a Sonata.

DP: That is why I decided I could legitimately record just the Fantasy.

JG: Another Schubert piece I know you did not play until after you came to the United States is the last sonata in B-flat, D. 960. Do you find a certain kinship between the first movement of that work and the also-relatively-late Fantasy [D. 894]?

DP: In a way, yes. There is a certain fatalism about both pieces, a communication with another world. And they provide examples of what Schumann called Schubert’s “Heavenly length.” There are many repeats, the same passages keep coming back, but if you took anything out, the whole essence of the work would be destroyed.

JG: The fantasy is marked “Molto moderato e cantabile.” That so many Schubert movements have the ambiguous indication “Moderato” seems to result in wildly divergent interpretations. I have heard recordings of the Fantasy in which different episodes are played at different tempos. You, on the other hand, maintain an even pace throughout.

DP: I cannot see it otherwise. If you play faster or slower, you damage the idea of the piece irreparably. It is such simple, divine music. . . . One of the best approaches to a recapitulation: B-flat minor ninth, then G minor ninth leading to the return to G major. Such free strolling between distantly related harmonies — and in Schubert’s time! This is simplicity in the best, divine sense.

JG: The Fantasy is harmonically adventurous, but structurally almost static, with the same episodes constantly recurring. While you play the whole piece at an even tempo, you do employ much rubato within phrases, yet in a manner that does not affect the overall stediness.

DP: This is the essence of rubato, [the great Russian musician Heinrich] Neuhaus’s definition of rubato playing: you must compensate. “Rubato” means “stealing.” Every time you speed up you are stealing time. Neuhaus said that, in order not to be a thief, you have to compensate (slow down) and return what you have just stolen.

JG: Both Schubert’s Fantasy and the slow movement of the Beethoven end quitely, fading away into nothingness. Yet the character of these hushed endings seems markedly different.

DP: Unlike Beethoven’s gloomy Largo, Schubert’s sadness is so light, as though he gladly accepts his fate. His music never tears out your soul like Beethoven’s or Tchaikovsky, who seems to die with each minor cadence. It’s a very different, typically Romantic philosophy of life.

JG: To push on, when did you start performing the Brahms?

DP: As with the Schubert, not until I came to the United States. I first played the Brahms in the early 1980s.

JG: Unlike Schubert, who made great strides harmonically, Brahms’s music changed hardly at all in that respect. So, what identifies Op. 116 as “late” Brahms?

DP: Brahms of the “100” opuses is different. It’s so mature and strong; he is at his best in each note. It’s incredibly pure music and, at the same time, so simple in its development — as only a genius could do. It is philosophy in sound — music made for forever.

JG: What is it that makes these seven pieces seem so unified?

DP: There is an element of monothematism. It is not too obvious, but you can definitely see and feel that all seven works are based on a similar thematic grain.

JG: I think there is also a separate thread that runs through the three Capriccios, on the one hand, and the four Intermezzos, on the other.

DP: The Capriccios [pieces 1, 3 & 7] are very stormy pieces. The first one starts much like Brahms’s First Symphony — as though someone turned on his radio at the top of a great emotional wave (in the words of Ivan Solertinsky [The great Russian critic]). The second of the capriccios is full of chromaticisms which finally burst into powerful, broad diatonic climaxes. The last capriccio is extremely strong music, especially the ending; it frames the whole cycle. The Intermezzos express deep, intimate feelings. The second piece [first intermezzo] expresses sadness and longing, but not tragedy. The fourth [second intermezzo] isn’t even melancholy; there is something pantheistic, something eternal about this music. The last two intermezzos have a special relationship to each other. The fifth piece is full of insecurity; it constantly flashes in and out, looking for something it cannot find. Then the sixth piece is “Father Lawrence” [from Romeo and Juliet]; it is full of wisdom and warmth, bringing peace to your soul and settling you after the inquietude of the fifth piece. That is why I play these two pieces with only a very short pause in between: the fifth piece needs to be balanced by the sixth.

JG: I think that pretty much covers the Brahms. Finally, to address the record as a whole, what makes it hold together so well as a program?

DP: Well, first of all, the similarity of keys [D minor, D major, G major, and D minor]. And, other than the Schubert, the program shows a lot of muscle and different human emotions. The Chaconne shows it even physically, and the Brahms. With Beethoven it’s the whole concept — it’s such a big piece. The Schubert is a kind of rest, an oasis. The pieces also represent four periods in the development of German music. In short, it’s a logically constructed program.

Album Details

Total Time: 73:25

Recorded: August 7 & 9, 1990 at WFMT Chicago

Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineer: Bill Maylone

Cover: Photo by William Partyka

Notes: Dmitry Paperno and James Ginsburg

© 1991 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 002