Store

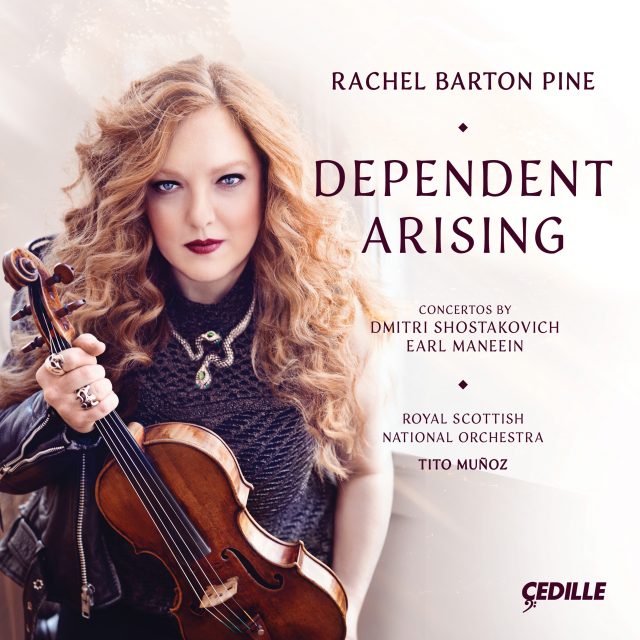

Violinist Rachel Barton Pine’s 24th recording for Cedille Records, Dependent Arising, reveals surprising confluences between classical and heavy metal music by pairing Shostakovich’s Violin Concerto No. 1 in A minor, Op. 77 with the world premiere of Earl Maneein’s “Dependent Arising” — Concerto for Violin and Orchestra, performed with the Royal Scottish National Orchestra under the baton of Tito Muñoz.

Known for her virtuosity, expressive playing, and extensive repertoire, Pine discovered her love for heavy metal as a teenager, and later performed at rock radio stations where she would intersperse covers of songs by Black Sabbath, AC/DC, and Metallica with works by Paganini and Ysaÿe.

The album explores connections between modern classical music and heavy metal and showcases Pine’s unique journey with these two seemingly disparate genres.

Now a staple of the classical concerto repertory, Shostakovich’s emotionally charged Violin Concerto No. 1 also holds a special place among metal enthusiasts, with its diverse movements ranging from haunting Nocturne to relentless Burlesque.

Earl Maneein is an acclaimed violinist and composer known for his unique and innovative fusion of western classical music, heavy metal, and hardcore punk. His “Dependent Arising” pushes the boundaries of traditional concerto composition and draws inspiration from the Western European classical music tradition, the world of “Extreme Metal,” and the composer’s practice as a Buddhist.

Both concertos explore themes of struggle, oppression, and defiance, which define Shostakovich’s oeuvre and resonate deeply with the essence of heavy metal music.

The album was produced by the Grammy-winning team of James Ginsburg and engineer Bill Maylone, with session engineering by the RSNO’s Hedd Morfett-Jones. It was recorded January 7–8, 2022 at Scotland’s Studio, Glasgow.

The recording was made possible in part by generous support from the Sage Foundation

Click here for a list of the RSNO musicians who played on the recording.

Click here for a playlist inspired by this album.

Preview Excerpts

Dmitri Shostakovich (1906–1975)

Violin Concerto No. 1 in A minor, Op. 77

Earl Maneein (b. 1976)

Dependent Arising — Concerto for Violin and Orchestra

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletPersonal note

Notes by Rachel Barton Pine

To my brothers in Earthen Grave and our loyal Gravedwellers family, this one’s for you.

I first discovered heavy metal music at the age of 10, when Santa Claus left a transistor radio under our Christmas tree. I was particularly drawn to the hard rock and mainstream metal that I found on classic rock and Top 40 stations. However, as I was exploring the end of the dial late one night, I stumbled upon a station that blew me away. The power and intensity of the music — Metallica, Megadeth, Anthrax, Slayer, Pantera, Sepultura … a genre called “thrash” — touched something at the core of my being.

As a teenager, I attended as many metal shows as I could between concert tours, lessons, and rehearsals. As drawn as I was to metal, it never occurred to me to play it on my violin until a few years later, when I was invited to do an interview on Rock 103.5, a popular rock station in Chicago.

I arranged some of my favorite metal songs to play on the air and was struck by the complexity of their structure and harmonies. The response to my performance was so positive that I began playing regularly on rock radio stations as part of my touring, interspersing covers of bands like Black Sabbath, AC/DC, and Metallica with works by Paganini and Ysaÿe. I’ve been overwhelmed by the results and still love meeting rock fans who heard me on the radio and were attending their first classical concert.

I was always sure that I loved the thrash subgenre so much because it represented such a stylistic contrast to the classical music I studied and practiced so intensely all day, every day. Over the years, however, I’ve had the opportunity to meet and talk with many members of my favorite metal bands. It turns out that they are fans of classical and heavily influenced by composers like Vivaldi, Locatelli, Brahms, and Ysaÿe. Van Halen even quotes a Kreutzer etude in “Eruption”! It turns out that classical and metal are far more similar than I ever imagined.

One of the things that I love about classical music is that it is a “universal language.” While its roots may have been from a Eurocentric culture, it is now composed and performed by people from all over the world. And, just like Bruch, Dvorak, Coleridge-Taylor, Bartok, Still, and so many others, classical music continues to draw on popular and traditional music roots to inspire and inform its art music.

It was in this vein that I originally reached out to Earl Maneein, the songwriter and lead violinist of the groundbreaking guitar-less death/hardcore band Resolution15, to write me a metal-inspired work for unaccompanied violin. Thankfully, he agreed to the commission and the result was a unique piece, Metal Organic Framework, that I premiered in New York in 2014. Tito Muñoz was in the audience, and the next thing we knew, he was commissioning Earl to write a violin concerto for me to perform with the Phoenix Symphony!

I couldn’t have hoped for a better result. Just as Bartok’s violin concerto is inspired by but transcends Hungarian folk music, Earl’s concerto elevates the rhythmic patterns and aggression of various heavy music subgenres to an expanded realm of storytelling. Those who know these musical roots will spot them (the world’s first blast beats created on symphonic percussion and timpani!), but those who approach it as any other contemporary classical work will fall in love with its emotional journey.

It was incredibly gratifying to experience the overwhelmingly positive response from audience members of all ages at the premiere performances in Phoenix. Most of these listeners had undoubtedly never heard, or possibly even heard of, death metal, but they thought that the new Maneein Violin Concerto was awesome!

When we had the opportunity to make this recording, there was only one piece with which I wanted to pair it: the Shostakovich Violin Concerto No. 1. There is perhaps no classical composer who is more beloved to metalheads than Shostakovich — there was even a longstanding Facebook page called “I Headbang to Shostakovich.”

Interestingly, my first encounters with Shostakovich’s music were the same year I received that transistor radio, at the age of 10. Each time I heard another one of his works, my reaction can only be described as shock and awe. What is it about Shostakovich’s music that causes this visceral response? Some music is designed to entertain us, to uplift us, to comfort us. Other music challenges us and makes us think by making us feel uncomfortable. Shostakovich’s complex music is defiant in the face of oppression. Perhaps that is the basis for its incredible appeal to heavy metal fans.

I love this concerto — the desperation of the first movement; the social justice protest of the second movement; the relentlessness of the third movement; and the fact that the last movement opens with an orchestral tutti due to Oistrakh’s request that he be given a few measures to wipe his brow after the cadenza! As a metalhead, the build-ups to the most aggressive moments of the cadenza are particularly satisfying, and the final “mosh section” of the concerto never fails to conjure up memories of my mosh pit days.

I want to extend a special thanks to José Viera and the Chicago Cosmopolitan Orchestra for supporting my final preparation by performing these concertos with me just before I went to the recording sessions. As always, the artistry of the RSNO is unparalleled, and Tito Muñoz’s talent never ceases to astonish.

Flying overseas for the recording session at the height of the pandemic was an extremely optimistic endeavor. I’ll never forget hearing about complicated contingency plans for if certain key musicians or other members of the team got ill but, amazingly, everyone stayed healthy, and we actually pulled it off.

Lastly, I’ve had the pleasure of collaborating with Cedille Records’ Jim Ginsburg since 1996, and as long as I’ve known him, I’ve been aware that Shostakovich is his favorite composer. So it is particularly special to have recorded this piece with, and for, Jim.

Notes on the Program

Notes by Earl Maneein

As I take on the daunting task of writing notes for Rachel’s album, I realize I have to get a few things out in the open right away: I’m neither a musicologist nor a music theorist. I’m a trained violinist who fell into the good fortune of writing a concerto for one of the finest violinists in the world. There are many people who could have written better program notes. However, as the composer of one of the two concertos, and a great admirer of Shostakovich’s works and the metal music that permeates my concerto, I can see that I am well situated to unpack latent consanguinity between these concertos. Please bear with me while I attempt this.

Dmitri Shostakovich’s music first slammed into me like a runaway train when I was a junior in high school. I was reading through his Eighth String Quartet then, in a group coached by Ani Kafavian. Before then, the only music I had ever encountered that expressed this level of alienation and fraught psychology was in the genres of metal and hardcore punk. To hear it in the music of a Russian composer, and one who was firmly embedded in the canon of great classical composers, was a revelation to me. My mind had constructed an imaginary wall between the forceful (and frankly unsettling) metal music I listened to for pleasure and the classical music I was studying as a violinist which, until that point, had always struck me as beautiful in a pleasant, non-threatening way.

That mental wall was obliterated by the fourth movement of the Quartet. I played a sustained pianissimo note while the rest of the group played three spine-chilling fortissimo, accented, heavy dissonant chords. It was the first classical music I heard that spoke so directly to me of terror, hate, and fatal fear. Ms. Kavafian told us that the three chords represented the secret police rapping on the door in the middle of the night — something that would have been at the forefront of Shostakovich’s mind when he wrote it. Shostakovich’s music cannot be separated from the time and place in which he lived. No one’s music can be, of course, but the issue of context is of primary importance in his case.

Stalinist Russia was terrifying, with death ready to find you at any time, for no reason whatsoever, other than falling out of the capricious favor of the totalitarian regime. Operatives would come up with an innocuous sounding doctrine, but one that would be used as justification to kill millions of people. Millions. So you’d get accused of violating some meaningless axiom, then you’d be denounced for something like “counter-revolutionary bourgeois formalism,” arrested, and possibly sentenced to death. Shostakovich knew these perils better than most: his last complete opera, Lady Macbeth of the Mtsesnk District (1934), after running successfully for two full years, fell afoul of Stalin himself. In fear for his life, Shostakovich denounced himself in groveling terms, and lived, albeit in a constant state of terror. His director for the opera was not so “fortunate.” Vsevolod Meyerhold was arrested in Leningrad, tortured until he confessed to being a British and a Japanese spy, and executed the day after his trial. Meyerhold’s wife was dispatched even more efficiently. After his arrest, she was stabbed to death in their apartment.

A dozen years later, when Shostakovich wrote his Violin Concerto No. 1 in A minor, Op. 77, he had just been denounced again, accused of “formalism” by some Mouth of Stalin named Zhdanov. The threat of arrest and execution was too real to be ignored: too many people (including me) could and can clearly discern in the piece a troubled protagonist struggling against unbeatable sinister forces. Shostakovich wisely shelved the Concerto for seven years, with David Oistrakh finally premiering it in 1955, two years after Stalin’s death. By then, Stalin’s successor, Nikita Khrushchev, had relaxed some of the terror, censorship, and oppression that were the hallmarks of the previous regime. Meyerhold and his wife, for example, were officially exonerated, postmortem, that same year. (I’m not saying Khrushchev was a nice guy. I’m just saying the bar set by Stalin was exceedingly low.)

Now let me speak of what I love about this Concerto. It consists of four movements: Nocturne, Scherzo, Passacaglia, and Burlesque, with a giant cadenza between the last two movements (scored as the end of the third). I remember studying the concerto as a graduate student preparing for a competition. At a lesson with my teacher, Danny Phillips, I didn’t observe the pianissimo dynamic that is indicated for large sections of the Nocturne. Danny said I was too open with the dark emotions that Shostakovich was conveying in the music. I was playing it as if I were emoting in a tragic Puccini aria for all to see and hear. According to Danny, Shostakovich’s indicated pianissimo demonstrates the intensity of repression. For me to disregard the dynamic was totally out of line with the understanding that, in Soviet Russia, people spoke their minds only to maybe their intimate partners, at night, under the covers, with the fear of the secret police ever palpably present. (I didn’t win the competition).

This first movement is followed by a “Scherzo” — Italian for “joke”— with the further tempo indication, “Allegro” (literally “merry”). The flute and bass clarinet bounce around in the opening segment, giving the piece an element of gallows humor. If death is staring at you, you might as well laugh, right? There are also klezmer elements in the movement — an especially ballsy move on Shostakovich’s part in light of Stalin’s anti-Semitic campaigns (which culminated in the “Doctors’ plot” affair of 1951–1953). These policies were generally couched in dull euphemisms such as “rootless cosmopolitans” (i.e., Jews) that were used as justifications for pogroms. It’s similar to when Richard Nixon spouted phrases like “forced busing” and “states’ rights” when he really meant that Black people in America didn’t deserve the same rights as white people.

The third movement, Passacaglia: Andante – Cadenza, has a feature I love: a super-unusual, 17-measure-long ground bass that conveys feelings of tension and dread. The subsequent cadenza is one of the most incredible things I’ve ever heard (or played). It comes out of silence at the end of this third movement, uses motifs from the movements that precede it as building blocks, and reaches a ferocity unparalleled, I think, in the violin literature.

I love the grim, relentless sarcasm of the last movement, Burlesque: Allegro con brio – Presto. I particularly love the Presto ending, based on a motif drawn from the Passacaglia, almost half-again faster than the tempo marked at the beginning of the finale. This kind of sudden tempo shift is also used in metal music to indicate a ramping up of intensity. It will often, at live shows, result in a sudden eruption of what is colloquially known as a “pit,” where an admittedly violent yet undeniably cathartic form of dancing happens called “moshing.”

Thus Shostakovich brings us to the subject of metal and also, therefore, to my Concerto. While I will not dare to compare my concerto to Shostakovich’s in terms of quality, I am comfortable claiming an affinity between the two works. Both present the listener with unpleasant emotions through music that openly confronts pain and suffering.

My Violin Concerto, “Dependent Arising” (Sanskrit: प्रतीत्यसमुत्पाद), was originally commissioned by Tito Muñoz after he heard Rachel play a solo violin piece she had commissioned from me. Tito had originally requested a short symphonic work. That was beyond my capabilities as a violinist who should have paid better attention to symphonic theory instruction at the conservatory. I preferred to use my comfort zone of violin composition as a point of departure. Tito was amenable, and Rachel readily agreed to perform, which I’m still super amped about. I am indebted not only to Rachel and Tito for giving me this incredible opportunity, and for their active participation and guidance throughout the composition process, but also to my friend, the composer Raphael Fusco, who generously sat with me for long hours functioning as a de facto composition teacher, asking only for beer and dinner in return.

The Concerto draws inspiration from the world of “Extreme Metal” (including, but not limited to the sub-genres of Thrash, Death, and Black Metal, Grindcore, Mathcore, and Hardcore Punk); from the Western European Classical Music tradition; and from my practice as a Buddhist. In early adulthood, I chose Buddhism as the philosophy best suited for me to address pain and suffering. The Concerto is a musical statement based on the Buddhist concept that all things arise in dependence upon other things. Nothing in the entire universe (or in any universe) happens independently, and all things lack self-existent substance. There is no cessation, no production, no annihilation or permanence, no coming or going, and no difference or sameness.

“Dependent Arising” consists of three movements: “Grasping at the self,” “The crows already knew of your grief. They will carry him home,” and “Gaté, Gaté Paragaté Parasangaté, Bodhi Svaha.”

The solo violin’s entrance in the first movement is meant to express the universal fear of death, and the resulting stunning realization, universal among humans, that all of our ambition, grasping, hopes, aspirations, dreams, and wishes are — as long as one remains tied to desire — ultimately fruitless.

The orchestra continues with the theme, communicating aggression and fear through “riffs” derived from the language of the Metal tradition. These themes are passed between soloist and orchestra throughout the work. One result of this hybrid of musical styles is that the soloist in this piece has to push his or her own voice over the orchestra in the most relentlessly aggressive way, as opposed to the traditional practice of bringing the orchestra to a soft dynamic in order for the soloist to be heard. That tension and aggression is a key feature of this work’s hybrid style.

The second movement is titled “The crows already knew of your grief. They will carry him home.” It was written shortly after a good friend died of kidney cancer. In early Buddhist traditions, monks would sit in meditation at a graveyard where bodies were left to decompose in open air. At one point during this guided meditation, the monk would be instructed to visualize a crow feasting upon his own corpse. Death, and all the emotions we experience surrounding it, remain the focus of this movement. It is a meditation on grief meant to augment the appreciation of daily life through a deeper understanding of its ephemeral nature, with both sadness and beauty addressed in the violin solos.

The third movement’s subtitle, “Gaté, Gaté Paragaté Parasangaté, Bodhi Svaha,” is the entire text of the Heart Sutra, one of the most famous scriptures in Mahayana Buddhism. Loosely translated, it means “Gone, gone, gone beyond, gone well beyond, Enlightenment that may be realized,” and is my personal wish for all beings, including myself. This movement is meant to embody wrath as a transformational tool which, in Buddhism, subtly but fundamentally differs from the concept of anger. Wrathful Buddhist deities serve the purpose of confronting us in our delusions, or pushing us into greater compassion — and they sometimes do it harshly. (The most common analogy used to explain wrath in this context is when a mother slaps the hand of a child who is about to touch the flame on a stove.) Used appropriately, wrath fiercely cuts through ignorance, defilement, and unskillful action.

Writing this piece called into play all of my available knowledge of both extreme and classical music. The solo violin part was written expressly for Rachel and her virtuoso skills. The orchestra is required to play adapted versions of “blast beats” (a single stroke roll played between the cymbal and snare of a drum set), “breakdowns” (a sudden tempo shift typically to more than twice as slow as the preceding section), “mosh sections” (a sudden tempo shift typically to more than twice as fast as the preceding section), and “chugs” (low range palm muted strokes originally on a guitar but adapted for violin and orchestra), all in the service of the musical statement I wanted to make.

My buddy Will Berger, a radio commentator for the Metropolitan Opera among many other things, likes to say, “Metal (and extreme music in general) is an expression of rage in reaction to the world we live in.” I agree. Metal, punk, and the giant umbrella of extreme music all are kinds of folk music born out of postwar discontent caused by a system where monetary profit is the end goal and the living conditions of the people actually doing the work are considered relatively unimportant.

Whether your life is expendable because you’re a cog in service to the state or because you’re a cog in the service of a multinational corporation is irrelevant. I am not attempting to make direct comparisons between communism and capitalism in relation to the suffering of individuals. I do, however, wish to draw some parallels between Shostakovich and metal, highlight the unexpected similarities between them, and propose reasons for it.

Tony Iommi, the guitarist of metal pioneer Black Sabbath, had to work at a factory in Birmingham as a young man. He famously lost his fingertips in an accident there. Many seminal musicians in punk and metal had childhoods where upward mobility was practically impossible and their future prospects were dead ends.

On a personal note, my mother was a night shift postal employee and I remember that at times, my father held three jobs at once, all in the service industry, and slept an average of three hours a night. I didn’t see much of him when I was child.

I grew up a working-class kid, with working class friends, who shared the same feelings of alienation, nihilism, boredom and discontent. We listened to thrash, death, and black metal, grindcore, and hardcore punk all the time. We were avid participants in the subculture. We had no patience for the lighter sub-genres of heavy metal like glam rock as represented by bands such as Motley Crüe or Poison. To us, they were poseurs. As teenagers who filtered our experiences through the prism of alienation, and who raged in reaction to the world we lived in, bands that wrote primarily about girls and partying were anathema. We saved money to buy entry level instruments, formed our own bands, played our own crappy music at DIY shows in church basements, eagerly dubbed cassette tapes of the newest Slayer album, and still saved our money to buy whatever new album came out, even though we probably already had a copied tape from someone’s older brother. We talked endlessly about whether Charlie Benante was a better drummer than Dave Lombardo, or whether Marty Friedman was better than Dave Mustaine. We debated whether Black Flag was better than Minor Threat and how cool Ian McKaye was for only charging five bucks a show even when Fugazi got to the point where they didn’t have to.

This gave us pleasure — more pleasure than what some of our friends would do, like set a sewer on fire, or vandalize bus stops. We were punks, but we weren’t hooligans because we loved music too much. We didn’t have time for both.

How does a guy like that (me) end up as a violinist writing a concerto? The short answer is that my parents chose to spend all their “extra” money on my violin lessons and I happened to love music and the violin. I was also skilled enough to manage to make it through the conservatory system relatively intact. Unlike some of my childhood friends, my musical education allowed me the opportunity to travel between social classes. These disparate influences ended up getting incorporated into how I write music.

How do you express pain and violence musically? How do you create catharsis for these negative states? The possible ways to express these feelings in music, as in any language, are limited and therefore are bound to have independently evolved similarities. Metal riffs are often repeated dissonant chords. When we use dissonances in metal, we call them “rubs.” Metalheads refer to the rhythmic modulations and odd meters that one finds in Shostakovich’s Scherzo and Burlesque as “breakdowns” and “mosh” sections. They inspire sudden eruptions of catharsis. These commonalities make it clear to me why Rachel chose to pair her excellent performance of the Shostakovich First Violin Concerto with my piece. I use the language of extreme music to fuel my work. I draw on my Buddhist practice of dealing with pain, violence, suffering, and death as inspiration.

Both of these violin concertos share expressions of terror, hatred, fear, horror, and sorrow as their primary mover. These are negative states that marketers, who emphasize the palliative aspects of classical music, usually gloss over with banal playlists and compilations along the lines of “Vivaldi Vacations For When Vicodin Isn’t Enough.”

I have to share how amped I am about Rachel’s recording of the Shostakovich. I think when her name gets mentioned, it’s generally to talk about her unassailable technique and how she crushes the 24 Caprices almost offhandedly. That’s true, but I don’t hear as much talk about how Rachel’s scholarly research, analysis, and personality contribute to her unique and incredibly well thought out interpretations. To me, Rachel strikes a great balance between scholarship and intuitive, primal gut expression. I’m so excited for everyone to hear not only the ferocity she brings to the forefront of this piece, but also her ability suddenly to show its fragility and brokenness. I wonder if she actually is bringing a little of her own knowledge, identity, and experience as a metalhead into the mix during the particularly brutal and nasty sections of the piece. This is just my speculation, of course. Rachel is someone who does her homework but does not sound like a clone of David Oistrakh — the standard sound people associate with Shostakovich concerto recordings, for obvious reasons.

In addition to thanking Rachel, I want to thank Tito, the Royal Scottish National Orchestra, and Jim and Bill at Cedille Records — everyone involved did such astounding work. Finally, thank you, Dear Reader for bearing with me. I hope you got something out of it, and I very much hope you enjoy this album, including my own concerto because, well, I wrote it.

Album Details

PRODUCER

Jim Ginsburg

SESSION ENGINEER

Hedd Morfett-Jones

EDITING AND MIXING ENGINEER

Bill Maylone

VIOLIN

Guarneri “del Gesù,” Cremona, 1742, the ‘ex-Bazzini, ex-Soldat’

STRINGS

Vision Titanium Solo by Thomastik-Infeld

BOW

Dominique Pecatte

COVER PHOTO

Lisa-Marie Mazzucco

SESSION PHOTOS

Sally Jubb Photography

PACKAGING DESIGN

Bark Design

RECORDED

January 7–8, 2022, Glasgow Royal Concert Hall, Scotland

PUBLISHER

Violin Concerto No. 1 in A minor, Op. 77 © 1957 Sikorski

Dependent Arising © 2017 Thin Veneer of Civilization ASCAP

CDR 90000 223