Store

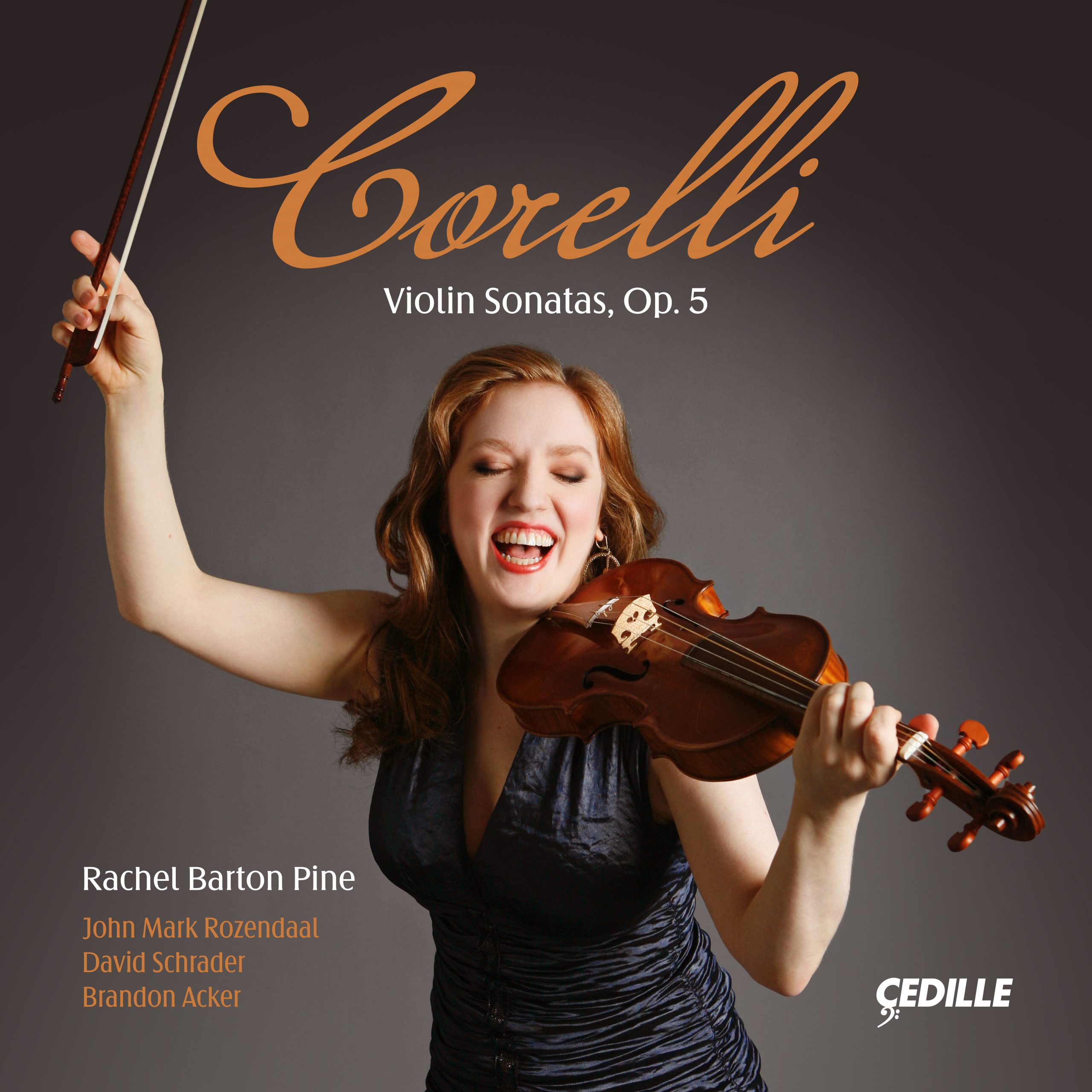

For her 24th recording for Cedille Records, violinist Rachel Barton Pine joins forces with Chicago’s leading period instrument specialists David Schrader, John Mark Rozendaal, and Brandon Acker to record Arcangelo Corelli’s seminal set of 12 Violin Sonatas, Op. 5.

“An exciting, boundary-defying performer” (Washington Post), Pine has been described as “a most accomplished Baroque violinist, fully the equal of the foremost specialists” (Gramophone). Known for her versatility across a vast repertoire — from Renaissance to heavy metal — she has studied period performance practice extensively and performs on the viola d’amore, renaissance violin, and medieval rebec. She has appeared as soloist with Apollo’s Fire, the Seattle and Indianapolis Baroque Orchestras, Baroque Band, and Ars Antigua, and has performed concertos with Nicholas McGegan, Jeannette Sorrell, and Frans Brüggen.

Published in 1700, Corelli’s Twelve Violin Sonatas are foundational in the evolution of both the sonata and concerto forms. This recording explores these compositions through a historically informed approach, utilizing an array of instruments, each chosen to enhance the expressive nuances of Corelli’s music.

Reflecting the era’s experimental spirit, the ensemble embraces the interpretative freedom suggested by Corelli’s original scores. Schrader alternates between organ and harpsichord, Rozendaal between violoncello and viola da gamba, and Acker performs on theorbo, archlute, and baroque guitar. Pine, inspired by the versatility of her colleagues, performs the famous “Follia” variations (Sonata No. 12) on an original-condition Gagliano viola d’amore, exploring this rarely used instrument in an authentic historical context.

Click here for a playlist inspired by this album.

Corelli: Violin Sonatas, Op. 5, was produced and engineered by the Grammy-winning team of James Ginsburg and Bill Maylone. It was recorded on February 21, 23, and 25, 2024 and April 29–May 2, 2024, at Nichols Concert Hall in Evanston, IL.

This recording is made possible in part by generous support from Gail Belytschko and Glory & Lynn Witherspoon.

Preview Excerpts

Archangelo Corelli (1653 - 1713)

Sonata No. 1 in D major

Sonata No. 2 in B-flat major

Sonata No. 3 in C major

Sonata No. 4 in F major

Sonata No. 5 in G minor

Sonata No. 6 in A major

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletA Personal Note

Notes by Rachel Barton Pine

In February 2018, when I performed with my period-instrument chamber ensemble, Trio Settecento, for a special 20th anniversary concert, Corelli was an obvious choice to be the focus. Corelli sonatas, after all, had been a core part of our repertoire since we named the ensemble in 1997, after the enthusiastic response to our recently released album of Handel Sonatas. But even well before that, Corelli and his music had played a significant role in my musical development and my musical connection to my trio partners.

I was first exposed to Corelli’s music when my childhood violin touring group performed his Concerto Grosso No. 8, the “Christmas Concerto.” I fell deeply in love with the piece and, throughout my youth, was fortunate to play an intimate chamber music version with friends as the prelude for my church’s Christmas Eve candlelight services.

At age 14, as I was browsing the stacks at my favorite sheet music shop, Chicago’s Performers Music, I came across a modern edition of Corelli’s opus 5, in which Corelli’s slow movements displayed a second line with many extra notes (from the “Roger” edition, c. 1715). I had no idea that adding notes to a classical composition was allowed and even expected. Eager to learn more, I sought out two of Chicago’s finest period instrument performers, John Mark Rozendaal and David Schrader. The very first baroque piece I studied with John Mark was a Corelli Sonata (No. 3 in C major).

Corelli also lies at the pedagogical root of much of the leading violin playing in the world today. As a teen, bitten by the genealogy bug, I was inspired to research my musical (rather than biological) ancestors. I worked backwards from one reference book to another at the library, reading composers’ biographies to create a pedagogical lineage stretching back three centuries: from my beloved teacher Almita Vamos to her teacher Louis Persinger to Ysaye to Vieuxtemps to de Beriot to Viotti to Pugnani to Somis to Corelli. This family tree is a humbling reminder of my own place in the continuing history of the violin, and of my duty to continue passing along these traditions to future generations of young artists.

There are a few interesting things to note about the making of this album. On this recording, I decided to hold the violin against my chest, rather than on my collarbone in the manner used most frequently by today’s baroque violinists. This decision was inspired by a 2014 article published in Music in Art: Christopher Riedo’s “How Might Arcangelo Corelli Have Played the Violin?” Citing evidence from engravings, drawings, and written descriptions, Riedo convincingly argues that Corelli held the violin this way.

The experiment yielded wonderful rewards. Not only did the slightly different use of the left hand necessitate subtle changes to tempos and timing, but more importantly, the bow arm’s different relationship to gravity created a noticeably different sound. Longtime fans of our group noticed the change in tone right away. The contrast is clear when you compare this album to our 2007 recording of Sonata No. 3 on Trio Settecento’s An Italian Sojourn (recorded on the same violin in the same hall but held on the shoulder).

Making a recording can open up artistic freedoms that are not necessarily feasible when on tour. For this album, we were able to use a variety of continuo instruments. David switches between positive organ and harpsichord; John Mark alternates violoncello and viola da gamba; and we also invited a fantastic plucked instrument virtuoso, Brandon Acker, to join us with his theorbo, archlute, and baroque guitar.

I was a little jealous that my friends were using multiple instruments. It struck me that because the famous “Follia” variations are in the typical viola d’amore key of D minor, I could play this last sonata on my other baroque instrument — an original-condition Gagliano viola d’amore made from the same tree as my original-condition Gagliano violin.

Because Corelli did not write “Follia” for d’amore, it proved the most difficult thing I had ever attempted on the instrument. The left-hand fingers fly around to different positions and the bow switches among the six strings in rapid and dizzying sequences. I hope you’ll agree that the effort was worth it! I feel the special voice of this instrument adds something fresh to this popular work, and I’m particularly pleased that both of my Gagliano fiddles are heard together on the same album.

Lastly, I took a very different approach to ornamentation. As with many baroque violinists, I started out by carefully experimenting with ornaments and then choosing ones that I liked for each moment I felt would be enhanced by them. Eventually, I was fluent enough in the language to comfortably extemporize these embellishments during live performances. I always pre-planned my extra notes for recordings, however, believing that edits made for tone quality, intonation, or ensemble might be overly complicated if I played different notes on different takes.

In making this recording, at the urging of my daughter, who is deeply immersed in composition studies, I challenged myself to play a little differently on each take. Rather than worrying about making sure that I always played the “best possible” ornament or trying to remember something nice that I had just done and replicating it, I let spontaneous inspiration flow. I forced myself to trust that my instincts and the producer’s wisdom would yield a good result. It was rather magical (and also quite exhausting) not to know exactly which notes I was going to play until they were appearing!

This album captures so much of what I love about living in the music world: communing with old friends with whom I share a musical “sixth sense,” being invigorated by our first collaboration with a new colleague, and drawing upon decades of experience with essential repertoire while exploring approaches to it that I’d never tried before. Thank you for joining us on this journey — I hope you find it as fulfilling as I have!

Rachel Barton Pine, 2024

Program Notes

Notes by John Mark Rozendaal

Virtually all writing on the career, achievement, and posthumous influence of Arcangelo Corelli (1653–1713) is packed with extravagant superlatives. For a pivotal quarter-century, Corelli was the essential musician for the most powerful arts patrons in the Eternal City. During those years, the works he published were marked for lasting fame, a prediction that history has fully borne out. It may be argued that Corelli altered or even invented the lineaments of the sonata, the concerto, the orchestra, the practice of harmony, the voice of the violin, and the persona of the violinist as we recognize them all today. At the very least, nothing about these things was ever the same after.

At the heart of this tremendous reputation lies a paradox.

Corelli’s fame seems to have been propelled by his performances with and compositions for larger ensembles. His trio sonatas (1681–1694) were a sensation when published and made Corelli’s international reputation immediately. These were performed by large ensembles with as many as six violins to open the meetings of the Arcadian Academy. Corelli performed his concerti grossi with the famous, large, skilled orchestras (sometimes comprising as many as 150 instrumentalists) that he led at all important occasions in Rome. Yet it is the duo sonatas of opus 5, with their intimate scoring, that live in our ears today and have done the most to sustain Corelli’s lasting reputation. What explains the enduring fascination of this exceptional book?

Before we may consider this question, some basic facts about Corelli’s legacy of published compositions are in order. Corelli’s entire œuvre (with very few outlying exceptions) is found in six publications, each containing 12 pieces, and each as clearly ordered as everything else about Corelli’s work. The first four books, published between 1681 and 1694, all contain trio sonatas, scored for two violins and bass instruments. The sonatas in Opp. 1 and 3 are of the type often called “sonate da chiesa,” or “church sonatas,” in which slow movements alternate with fast, mostly fugal movements. The sonatas in Opp. 2 and 4 are “sonate da camera,” or “chamber sonatas”: sequences of movements mostly in binary form, often dance types, resembling dance suites. (The sixth and final book contains concerti grossi for string orchestra.) Op. 5 extends this strict division of types by offering in its first part, six church sonatas and in its second part, six chamber sonatas. Sonata 12 culminates the book with something different, a set of variations on the traditional set of chord changes widely known as “Follia.” This theme, first appearing in the late 15th century, was among the most popular of the set of materials used by musicians of the high Renaissance and Baroque eras to compose or improvise upon, and to display fecundity of imagination and instrumental prowess. Corelli’s set is a pinnacle of the genre.

Corelli was praised during his lifetime — by people well equipped to judge — as one of the greatest living violinists, and his works have been essential repertoire and study material for violinists of all generations; yet Corelli’s violin writing actually eschews the technically demanding stunt work that violinists, both before and after, have usually cultivated to make great reputations. Corelli’s music also largely lacks the flashy features that we associate with the “baroque”: exaggeration, distortion, grandiosity, irregularity, shock. Corelli’s music is distinguished by its rhetoric of balanced formality, compositional discipline, directness, and simplicity. How does such a unique and persuasive art come into being in a place like 17th century Rome? Some features of Corelli’s biography and personality may be suggestive.

Arcangelo Corelli received his music education in Bologna, a city that was at once the seat of the world’s oldest university, a center for printing and publishing, and a hotbed of musical activity. Little is known for certain regarding what his precise activities in Bologna might have been, but by the age of 17, Corelli had already been admitted to the prestigious Accademia Filharmonica di Bologna. At this point, he may have already felt that even this great city did not offer the scope of career he hoped for, because soon after receiving this honor the young Corelli decamped for Rome.

Records of Corelli’s life in Rome suggest a personality suited to enjoying and sustaining enduring and harmonious personal relationships with a brilliant array of colleagues and patrons. Soon after his arrival, sometime before 1675, Corelli became a protégé of Queen Christina of Sweden (1626 –1689). A legendary intellect, unconventional personality, and patron of the arts known as the “Minerva of the North,” Christina had become Queen of Sweden in her own right at the tender age of six, acceded to the throne at 18, and renounced it four years later when she converted to Roman Catholicism — a conversion that was celebrated throughout Catholic Europe. After a triumphant tour of the continent, Christina settled in Rome, where she established the famous academy eventually known as the Accademia degli Arcadi: an assemblage of princes, prelates, and their artist protégés who shared new works of poetry and music. The academy was undertaking a reform of Italian poetry, rejecting what they considered the gaudy, melodramatic “Marinist” style in favor of a simpler, more direct and natural expression. In this circle, Corelli soon came into contact with an astonishing set of intriguing and powerful people. At this time, Alessandro Stradella, a composer whose biography is no less dramatic than his startling music, was still employed by Queen Christina (until he fled the city to avoid retribution for his involvement in an extortion scheme). The young Alessandro Scarlatti was then living in an apartment in the palace of the great sculptor and architect, Gian Lorenzo Bernini. Corelli could have heard, and might even have participated in, the first performance of Scarlatti’s breakthrough hit opera, Gli equivoci nel sembiante (Folly in Love), given in the palace of Bernini’s student, Giambattista Contini.

In 1687, Corelli moved into the palace of Cardinal Benedetto Pamphili, along with his student, colleague, and companion for life, Matteo Fornari. The fabulously wealthy Pamphili composed texts for cantatas and oratorios by Scarlatti, Bononcini, Handel, and many others, which he sumptuously produced; formed an important collection of Flemish paintings at his palace in the Corso; and served in prestigious appointed posts, including librarian of the Vatican collections. After Queen Christina died in 1689 and Pamphili temporarily left Rome to serve as papal legate in Bologna in1690, the residence of Cardinal Pietro Ottoboni, in the Palazzo della Cancelleria, became the new center of musical life in the city, and Corelli and Fornari went to live there. In addition to boasting an impressive legacy of artistic patronage and literary achievement, the exuberant Ottoboni decorated his bedroom with paintings of his mistresses as saints, and may have fathered between 60 and 70 illegitimate children.

At some point during his early years in Rome, Corelli met instrumentalists with whom he formed lasting musical and personal bonds, including Fornari, cellist Giovanni Lorenzo Lulier, and harpsichordist Bernardo Pasquini. Lulier and Pasquini were both opera composers, and both performed frequently with Corelli. The people mentioned above recur in each others’ biographies again and again in connection with lavish productions of operas, oratorios, ecclesiastical events, state occasions, and Academy gatherings featuring floods of new music performed in magnificent palaces and cathedrals. This conjures a remarkable society of cooperative and competitive artistic achievement in which our hero, Arcangelo, emerges as a calm center, simultaneously appearing as a pinnacle of artistry and a paragon of modesty and simplicity.

A charming account of Corelli is found in the memoirs of the Scottish gentleman, John Clerk of Penicuik. In 1695, the 19-year-old Clerk embarked on a continental education. When he arrived in Rome, he undertook to have lessons with the best masters available. The traveler reported: “I have heard Corelli plays several times, but I was strongly baulked of my fancy when I saw him, for I thought to have seen a gentill fellow, whereas he made, for all the world, just such a figure as one of our Dutch fiddlers, but indeed he plays like an angell.” And later, “My masters were Bernardo Pasquini, a most skillful performer on the Organ and Harpse, and Archangelo Correlli, whom I believe no man ever equalled for the violin. . . . He gains a great deal of monie, and loves it for the sake of laying it all out on pictures . . . He seldom teaches anybody; yet, because he was pleased to observe me so much taken with him, he allowed me 3 lessons per week during all the time I stay’d at Rome. He was a good well-natured man, and on many accounts deserved the Epithet which all Italians gave him of the divine Arc Angelo.”

Appearing in 1700, Corelli’s Op. 5 contains a dozen sonatas scored for “violino e violone o cimbalo” (violin and cello or keyboard). One of the most striking and pleasing features of the music in this remarkable book is the constant duetting between the two parts. Even when the cellist’s part is not assigned imitative figuration, its lines are always propulsive, rhetorically contoured, and constantly in dialogue with the violin. Except for the opening salvo of Sonata I, Corelli never leaves his cellist companion with the long passages of pedal tones — whole notes and shapeless lines having no function other than harmonic support for a violinist’s display of virtuosity — that we encounter so often in the music of violinist composers such as Heinrich Biber or Giovanni Batista Fontana. In every phrase of the book, we find the two instrumental voices in dialogue, constantly provoking, soothing, questioning, answering one another, like old friends who never tire of hearing each others’ stories. In Corelli’s hands, the discipline of traditional imitative counterpoint (that he mastered at Bologna), assisted by perfectly calibrated harmonic propulsion becomes a perfect vehicle for a vibrant social exchange guided by an “Arcadian” sense of concord. By some miracle, this music is both palpably of its particular time and place and timeless in its capacity to satisfy and excite new generations of performers and listeners.

As to instrumentation, the score’s title page suggestion leaves much room for interpretation. The word “violone” might mean the bass instrument of the violin family (the slightly larger immediate precursor of the violoncello) but could mean any bowed bass instrument. The word “cembalo” may mean a harpsichord, or it might mean any keyboard instrument. Composers of this era understood that when they gifted their music to the world through publication, people would do with it what they will, including trying it on every kind of instrument and combination. We know that Corelli himself performed his chamber music with large ensembles doubling parts. We also know that Corelli’s collaborators included viol players and lutenists. (Corelli actually owned an English viola da gamba.) In order to explore the myriad possibilities of Corelli’s bass line, and to give this recording uncommon variety, we have assembled an instrumentarium including two different keyboards (harpsichord and organ), two different bowed bass instruments (cello and viola da gamba), and three different plucked and strummed instruments (archlute, theorbo, and baroque guitar). We then chose different combinations for each movement based on what seemed to best suit Corelli’s writing in each case. Even “violino” is subject to interpretation as Rachel Barton Pine chooses to perform the 12th Sonata (“Follia”) on viola d’amore. Our set of solutions is, of course, just one among a vast array of possibilities.

In 1713, having made his will and moved from the Cancellaria to his brother’s house, Arcangelo Corelli died as he had lived, with grace and companionship. Corelli’s bequests included violins and publishing rights left to Fornari, a picture to Ottoboni, and gifts of money to servants and family members. Ottoboni arranged for his burial in the Pantheon, where the anniversary of his death has been observed for many years with performances of his concertos.

Album Details

Producer James Ginsburg

Session Engineers Bill Maylone and Eric Arunas

Editing, Mixing, and Mastering Bill Maylone

Score Marking Jeanne Velonis

Violin Nicola Gagliano, 1770, in original, unaltered condition

Violin bow Michelle Speller, replica of 17th Century model

Viola d’Amore Nicola Gagliano, 1774, 6+6, in original, unaltered condition

Viola d’Amore bow Christopher English, replica of 18th Century model

Violin and Viola d’Amore strings Gamut Music, Inc.

Luthier Whitney Osterud

Viola da Gamba William Turner

Violone (cello) Anonymous Tyrolean maker, 18th Century

Bows Markus Laine and Julian Clarke

Harpsichords

Willard Martin (Bethlehem, PA), 1997 single-manual instrument after a concept by Marin Mersenne (1617)

John Phillips (Berkeley, CA) Flemish single manual modeled after Albert Delin (provided by Stephen Alltop)

Chamber organ Gerrit Klop (Netherlands), modeled after Esaias Compenius (1610) (provided by Stephen Alltop)

Theorbo Klaus Jacobsen

Archlute Jaume Bosser

Baroque guitar Julio Castaños Soler

Recorded

February 21, 23, and 25, 2024 and April 30–May 2, 2024 at Nichols Concert Hall in Evanston, IL

Cover Bark Design

Cover Photo Janette Beckman

Graphic Design Bark Design

CDR 90000 232