Store

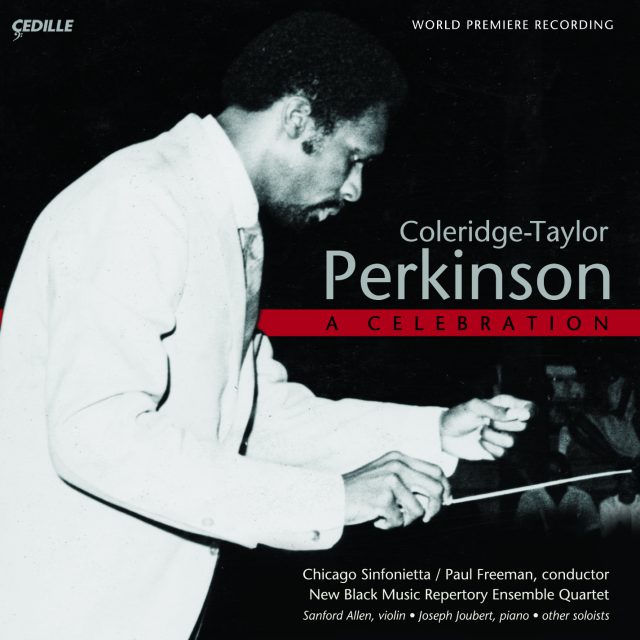

Coleridge-Taylor Perkinson: A Celebration

Chicago Sinfonietta, Paul Freeman

Coleridge-Taylor Perkinson, Sanford Allen, Tahirah Whittington, New Black Music Repertory Ensemble

This CD celebrates the life of innovative American composer Coleridge-Taylor Perkinson (1932-2004), whose accomplishments spanned the worlds of jazz, dance, pop, film, television, and classical music.

World premiere recordings of Perkinson’s orchestral, chamber, and solo instrumental works showcase his distinctive blend of Baroque counterpoint; energetic, streamlined American Romanticism; elements of blues, spirituals, and black folk music; and a rhythmic ingenuity all his own.

Performances by the Chicago Sinfonietta and conductor Paul Freeman, Chicago’s New Black Repertory Ensemble Quartet, and distinguished soloists.

Preview Excerpts

COLERIDGE-TAYLOR PERKINSON (1932-2004)

Sinfonietta No. 1 for Strings

(15:17)

Quartet No. 1 based on "Calvary"

(17:04)

Blue/s Forms for Solo Violin

(7:26)

Lamentations: Black/Folk Song Suite for Solo Cello

(15:38)

Artists

4: Joseph Joubert, piano

5: New Black Music Repertory Ensemble Quartet

8: Sanford Allen, violin

11: Tahirah Whittington, cello

15: Ashley Horne, violin

16: Sanford Allen, violin

Jesse Levine, viola

Carter Brey, cello

What the Critics Are Saying

“It is very difficult,” said the late Coleridge-Taylor Perkinson (1932-2004) in answer to an interviewer’s question, “to say what black music really is.” Therein lies the dilemma for the modern African-American composer who cannot deny his rich cultural heritage but whose goals transcend that immediate heritage to embrace the whole world of the classics.

To be sure, Perkinson forsake the groves of Academe to make his way in the world as a practicing musician. He wrote arrangements for popular and jazz artists like Marvin Gaye, Donald Byrd, and Harry Belafonte, and he was the pianist of Max Roach’s quartet in 1964-65. He uses the language of the blues in his Blue/s Forms for Solo Violin (1972) and the melody of the Negro spiritual “Calvary” to provide a rich source of motives and intervals for counterpoint in his Quartet No. 1 (1956) and the third movement of his Black/Folk Song Suite for Solo Cello (1973). On the other hand, if I played Perkinson’s Sinfonietta No.1 for Strings (1954) or his Grass: Poem for Piano, Strings and Percussion (1956) for you, composer unknown, and asked you what modern “Scandinavian” we were listening to, you might be none the wiser.

For Perkinson was one of the select number of 20th century composers who looked back most often to Johann Sebastian Bach for inspiration. (Not so far a stretch for CTP, since today’s jazz musician would find himself more at home in the world of Bach than he would most classical music since that time. Just note the face of the average

classical musician if you ask him to “realize” a basso continuo – the jazz artist does the equivalent every day – and you will see what I mean.) Perkinson’s music exhibits superb clarity of thought in line and counterpoint. He loves to explore the ambiguity between major and minor modes created by the so-called “blues notes,” the lowered thirds and sevenths. The effect of his music is honest and moving. Movement for String Trio (2004),

a deathbed composition, is, at 3:56, a perfect elegy in a small

compass.

The present Cedille offering, Coleridge-Taylor Perkinson: A Celebration, showcases the talents of violinists Sanford

Allen and Ashley Horne, violist Jesse Levine, and cellists Tahirah Whittington and Carter Brey, and the Chicago Sinfonietta under Paul Freeman. Some outstanding talents also went into the recording team: James Ginsburg and Judith Sherman were the producers, Sherman and Bill Maylone the engineers. How overdue this tribute is, may be gauged by the fact that this is the first time I have encountered the composer since I began as a reviewer in 1982.

This posthumous anthology consisting of selections from 50 years of work by composer Coleridge-Taylor Perkinson (1932–2004) includes six world premieres—that is to say, it took 50 years for this man’s lifetime output to be recognized. Perhaps that is not so shocking. After all, how easy was it for a black man in the 1950s to obtain a bachelor’s and master’s degree from Manhattan School of Music, and compose his first major work at the age of 22 within the confines of a segregated society? But Perkinson, the namesake of black British composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (1875–1912), didn’t consider himself generically a black composer. Whether or not he allowed himself to be typecast as an ethnic artist, Perkinson’s interpretation of white, WASP, and Western musical convention is spiked with vintage blues and jazz. His music is, therefore, in an uncanny and paradoxical way, the reverse of the cultural plundering associated with Gershwin’s and Dvorák’s musical appropriations. Consequently, if Perkinson’s music isn’t especially innovative, we shouldn’t be surprised that a victim of discrimination and ghettoization would not choose to further isolate himself by throwing 12-tone rows into the mix. After all, experimentation is the spawn of prosperity, not the privilege of hardship.

Perkinson’s Sinfonietta No.1 for strings, composed in 1955, might have been considered, if composed by a young Caucasian, the work of a wunderkind. The precocious piece is an homage to Bach, and throughout his life Perkinson returned to fugal writing as a religious rite of appreciation for the German master. Two years later, Perkinson began to infiltrate into his technique the echoes of his ancestor slaves. Quartet No. 1, based on “Calvary” (Negro Spiritual) weaves together the dualism of his segregated world into one lucid harmonious dream.

The next selection on the disc was composed 20 years later. One wonders what happened in the intervening years, though we know that Perkinson had the opportunity to work with Leonard Bernstein, Max Roach, Alvin Ailey, Jerome Robbins, Marvin Gaye, and Harry Belafonte. He also co-founded and conducted the Symphony of the New World. Blue/s Forms for solo violin (1972) is a deep reverie of black experience as seen through the filter of Paganiniesque writing. Sanford Allen plays it with tender feeling. Equally luscious is Lamentations, a black/folk song suite for solo cello, played by Tahira Whittington.

Just before his death, Perkinson composed the last selection on the disc, Movement for String Trio. It is a profoundly sweet, sad, Barberesque, self-requiem for a man who should have been heard, and one hopes will be heard now—though he won’t be here to enjoy the long overdue recognition.

March/April 2006

By David Wolman

“Leonard Bernstein is the only other giant I know of who could do everything that ‘Perk’ could do.”

Coleridge-Taylor Perkinson chose to be an eclectic rather than an ethnic composer. Sinfonietta for Strings and Grass, the opening works on this “Celebration” CD, are vigorous specimens of 50s neoclassicism warmed in their slow sections by string writing reminiscent of Barber’s.

Perkinson does not neglect his African-American heritage. The Quartet 1, ‘Blues Forms’ for solo violin, and Lamentations, a Black/Folk Song Suite for cello, all effectively fuse blues and jazz motifs with classical or Bachian structures. The most overtly “black” of these is ‘Louisiana Blues Strut’ for solo violin. Carter Brey, Sanford Allen, Ashley Horne, Joseph Joubert, the Chicago Sinfonietta, and the New Black Music Repertory Ensemble Quartet all deliver eloquent performances. This is a worthy recording: 79 minutes of varied, expressive music by an undervalued composer. [March 2006]

Program Notes

Download Album BookletColeridge-Taylor Perkinson (1932-2004) A Celebration

Notes by Gregory Weinstein

In an interview for the 1978 book The Black Composer Speaks, Coleridge-Taylor Perkinson was asked to define black music. He responded:

I cannot define black music. I could say that it is a music that has its genesis in the black psyche or the black social life, but it is very difficult to say what black music really is. There are kinds of black music, just as there are kinds of other musics….

In this response, Perkinson has identified a principle issue confronting scholars and critics of African-American music: how to define it, if indeed there is a unified “it” to define. Many writers have presented perspectives on this problem, perhaps most notably Samuel A. Floyd, who speaks of “Call-Response,” an inclusive process of African-American musical troping. Perkinson’s views were far more pragmatic and personal. He said the only uniquely black aspect of his music was “inspiration”. Only you can decide if the life you live is significantly black; no one can decide that for you, and I don’t think that it’s right for anyone to pass judgment on the nature of your involvement.”

Perkinson came of age as a composer in the 1950s, a time of stark division in the American classical music world. On one side was a group of composers committed to increasingly arcane experiments. Milton Babbitt famously noted his desire to move composition into the academic sphere, rejecting the listening public and wondering “Who cares if you listen?” At the same time, the canon of old and new Romantic composers became increasingly entrenched in the concert world. Mainstays of the concert hall, such as Beethoven, Brahms, and Mahler, were being joined by twentieth-century counterparts such as Sergei Rachmaninov and Samuel Barber.

The “high art” canon of classical composers has traditionally been inhospitable to black composers. Not one has truly entered into the classical mainstream. (Perhaps the most prominent twentieth-century African-American composer, William Grant Still, found his matier nearly untenable: critics condemned his early “ultramodern” work as too complex, then dismissed his later “racial” works as overly simplistic.) Thus, Perkinson’s pragmatic approach to the notion of a “black composer” could be seen, at least in part, as a tactical move: a desire to be judged solely on the merits of his music.

Perkinson’s diverse career must be positioned against the racially restricted world of classical music. He received an academic training in composition, studying with Vittorio Giannini at the Manhattan School of Music and Earl Kim at Princeton University. Yet he refused to enter the isolated world of academia, preferring instead a diverse array of musical jobs. He produced a great deal of “high art” music, but he was equally well-versed in jazz and popular forms: he briefly served as pianist for drummer Max Roach’s quartet and wrote arrangements for Roach, Marvin Gaye, and Harry Belafonte.

In light of Perkinson’s musical catholicity, one must resist the temptation to impose constricting artistic visions on his compositional output, since he clearly imposed no boundaries on his models. Perkinson wrote the earliest work on this disc, the Sinfonietta No. 1 for Strings, in 1954 when he was 22, although it was not premiered until 1966. Stylistically, the Sinfonietta reveals the influence of several composers, particularly the counterpoint of his “teachers,” J.S. Bach and Vittorio Giannini, and the idiom of the day’s “Romantic” American composers. The slow movement, for example, seems reminiscent of the Adagio from Samuel Barber’s String Quartet, composed nearly twenty years earlier (better known in its later configuration as Barber’s Adagio for Strings), while the last movement resembles somewhat the style of Aaron Copland with its expansive melodic fourths, particularly in the lyrical middle section. Despite its tangible connections with other composers, the Sinfonietta reveals many characteristics that Perkinson would develop throughout his career, including pointed and controlled dissonance and metrical ambiguity (particularly in the third movement, where he changes meters frequently and disrupts the rhythmic flow by altering the relative positions of the themes).

Grass, a work for piano, strings and percussion, dates from approximately the same period as the Sinfonietta and its compositional style is quite close to the Sinfonietta’s first movement. While the Sinfonietta was nominally an autonomous composition, Grass is based on an eponymous poem by Carl Sandburg.

Perkinson explained, “It was written during a time when I imagined that I was going to be involved in the Korean conflict and was written from the perspective of a black person being involved in the Korean conflict.” Although he declined to elaborate further or describe how the music relates to the poem, leaving such connections to the listener’s imagination, the repeated opening motive is obviously based on the rhythm of the poem’s refrain: “I am the grass, I cover all.” The piano and percussion effectively contrast against the strings. Perkinson employs rhythmic devices similar to those in the Sinfonietta, but to greater extremes: displacements are more abrupt, meter changes and metrical ambiguity more common, and repetition is frequently employed. The work is in a ternary form, with a placid middle section bracketed by two active outer passages. Like the Sinfonietta, Grass is a tonal composition, though it employs a high degree of dissonance, often more exposed than in the earlier work (e.g., the piano chords before the middle section).

Perkinson composed his Quartet No. 1 during the same period as the Sinfonietta and Grass, and its use of dissonance and counterpoint is often similar. The quartet, however, marks one of the first times Perkinson presents an explicit trope on an African-American tradition: the composer acknowledges in the title that the quartet is “based on ‘Calvary’ (Negro spiritual).” Perkinson was familiar with the spiritual from church services but cautioned, “When I sat down to write this string quartet, I was not trying to write something black; I was just writing out of my experience.” The spiritual provided the basis for the melody of the first movement, although it is transformed to the syncopated and angular style characteristic of Perkinson’s compositions from this period. The movement is generated through the development and transformation of the Calvary melody, providing a rich source of motives and intervals for Perkinson’s counterpoint. If the spiritual tune is present in the second and third movements, it is heavily disguised. Both movements — the second is slow and expressive while the third (a rondo) is more agitated — feature striking alternations of homophonic passages with precise counterpoint and voice transfers.

Although Perkinson expressed his supreme enjoyment for writing for large ensembles, he often seemed most at home when composing with a specific player in mind. Perkinson wrote Lamentations, a suite for solo cello, in 1973 for cellist Ronald Lipscomb, who gave the premier performance at New York’s Alice Tully Hall. The piece is subtitled “Black/Folk Song Suite;” the composer explained, “the common denominator of these tunes is the reflection and statement of a people’s crying out.” The first movement, labeled “Fuging Tune,” draws on both the traditional fugue, as developed by J.S. Bach (one of Perkinson’s favorite composers and primary influences), and a type of composition called “Fuging Tunes,” popularized by 18th-century American composer William Billings. Perkinson composed the second movement, “Song Form,” in an AABA format, a parallel to the similarly titled movement of his Sinfonietta (if not to the earlier work’s tone and texture). The third movement features another trope of the Calvary spiritual. Titled “Calvary Ostinato,” the movement features a repeating pizzicato bass line over which Perkinson composed another form of the Calvary melody. In the virtuosic final movement, Perkinson has the cello maintain a constant pulsing pedal note (alternately D and C) while creating intricate melodies around the repeated note, including a brief quotation of Stravinsky’s Le Sacre du Printemps.

Blue’s Forms, a 1972 work for solo violin, takes much the same format as Lamentations. Like the cello piece, it is intimately connected to its dedicatee, violinist Sanford Allen, who premiered the work at Carnegie Hall. Based on traditional blues schemes, the work is in three movements and is based in the key of G — the lowest open string on the instrument. Perkinson exploits the ambiguity between major and minor modes created by the so-called “blue notes,” the lowered third and seventh degrees of the scale. This ambiguity is present from the opening chord, where the blue third melts into the major. The first movement is in AABA form with the A sections 8 bars in length and the B extended to 12 measures. There is a great deal of repetition between sections — the A’s are nearly identical, but the harmonic plan seems more in line with song form than with traditional blues. The second movement is to be played muted and freely, employing slippery diminished seventh chords and syncopation. As with the opening movement, it ends on a half-cadence, leading into the finale. The third and final movement is a dizzyingly rapid perpetual motion. The meter varies, using different multiples of sixteenth notes, but the end result is one of continuity with disorienting syncopations and slight variations in meter.

Composed nearly thirty years after Blue’s Forms, Perkinson initially conceived of Louisiana Blues Strut as a fourth movement for the earlier work, but he ultimately left it separate, remarking, “I just couldn’t get my head in the same place.” Subtitled “A Cakewalk” (a dance form reputedly with origins in the musical practices of slaves but with many modern descendants), this movement takes the form of a rondo with a laid-back groove.

On one level, Blue’s Forms and Louisiana Blues Strut are sophisticated works for solo violin that both visually and aurally remind one of virtuosic compositions dating back to Bach’s Sonatas and Partitas. The pieces also draw attention to the correspondence between the repetitive harmonic scheme of the blues and that of Baroque forms such as the chaconne and passacaglia. However, Blue/s Forms (and its successor) is also a subtle commentary on the blues, invoking that genre’s varied origins and formal components while blending it with the traditions of classical solo composition.

The string trio movement presented on this disc is Perkinson’s final composition, written quite literally on his deathbed in February and March of 2004. This movement is unique among the works presented on this memorial: its utter simplicity stands apart from the complex musical designs of the Sinfonietta and “Calvary” Quartet (for example). The cello presents a repeated chromatic descent, so characteristic of operatic lament basses, while the violin and viola trade and embellish a minor-mode theme. Yet even here, in this most poignant movement, Perkinson’s rhythmic games are afoot, as he occasionally adds and subtracts a single sixteenth note from a measure. It seems appropriate that Perkinson would compose at the end a work whose deliberate counterpoint so clearly evokes Bach, one of the earliest and most enduring influences on his unique compositional style.

Gregory Weinstein is a Ph.D. student in ethnomusicology at the University of Chicago. His research interests include African-American music, including hip-hop and popular music.

Album Details

Total Time: 79:00

The Sara Lee Foundation is the exclusive corporate sponsor.

This recording is also made possible in part by grants from The National Endowment for the Arts, The Aaron Copland Fund for Music, and The Louis M. Rabinowitz Foundation.

Producers: (Tracks 1-7, 15) James Ginsburg; (Tracks 8-14, 16) Judith Sherman

Engineers: (Tracks 1-7, 15) Bill Maylone; (Tracks 8-14, 16) Judith Sherman

Recorded:

(Tracks 1-4) May 18-19, 2005 at Lund Auditorium at Dominican University, River Forest, Illinois

(Tracks 5-7, 15) May 6, 2005 at WFMT Chicago

(Tracks 8-14, 16) April 5 & 8, 2005 at Academy of Arts and Letters, New York City

Graphic Design: Melanie Germond, Pete Goldlust

Photos of Coleridge-Taylor Perkinson, courtesy of the Center for Black Music Research, Columbia College Chicago.

All works © Coleridge-Taylor Perkinson.

All works except Blue’s Forms and Movement for String Trio engraved and edited by Joe Muccioli, who supervised the recording sessions for Sinfonietta No. 1 and Grass.

© 2005 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 087