Store

Lera Auerbach’s 24 Preludes for violoncello and piano (1999) receives its world-premiere recording on Celloquy in a performance by Ani Aznavoorian, an award-winning American cellist of international stature, and Auerbach, a Russian-born virtuoso pianist and one of the most widely-performed composers of the new generation.

Auerbach is the youngest composer on the roster of Hamburg’s prestigious international music publishing company Hans Sikorski, home to Shostakovich, Prokofiev, and Schnittke. “Her music is lyrical, passionate, and often seems to straddle the past and present,” observed the host of a recent Canadian Broadcasting Corporation program devoted to Auerbach’s multi-faceted career.

The Chicago Reader called the 24 Preludes “an enthralling work of great invention and power.” The San Francisco Chronicle said, “Each of these short pieces . . . is a lyric poem in music, creating a mood, a melodic notion, or a completely imagined microcosm. . . . The range of Auerbach’s inspiration is phenomenal.”

Aznavoorian and Auerbach have played the 24 Preludes numerous times, notably on stage at the Hamburg State Opera House during Hamburg Ballet performances of Auerbach’s Préludes CV, which incorporates the cello Preludes. The two musicians are longtime friends and collaborators who met as undergraduates at New York’s Juilliard School.

Preview Excerpts

24 Preludes for violoncello and piano

Sonata for violoncello and piano

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletPoems by Lera Auerbach

Notes by Andrea Lamoreaux

FUGUE

I am choreographing my own discontent.

The days pile up in dried and frugal vanity,

busying maneuvers of ever-moving hands,

swinging pendulum from suicide to sacrifice,

from ecstasy to gratitude within all shades of gray.

The fugue winds tighter;

I still remember its theme, but its countersubject leave me gasping for air.

The counterpoint is poisonous in any larger quantities,

and I don’t have an antidote to this infectious music.

My fever is running higher.

The hot fingertips touch the untouchable body of the fugue —

it can’t be captured fully in the nets of notes and measures,

it runs away wildly, through the untamable laughter

of gods and daemons, whoever is guarding the gates of sound,

the wailing chimeras of heaven and hell.

I look into the black flame.

Soon it will consume my days, it already freezes my heart, and takes all I still call ‘my own,’

turning it into dry harvest which burns — oh, so brightly —

until it’s no longer, until it’s only ashes, until it returns to dust,

becomes that silent note after the end, but just before the applause

while the conductor’s hands are still holding the wings of a musical phrase

and the audience holds its breath as not to disturb the magic;

except no one is waiting for me at the other end, there is no applause nor greeting, no bravi,

but only that moment of infinite loneliness when sound dies.

ABYSS

It is always there, waiting.

As I wake, as I jog in the morning or I re-read my favorite poem —

the one which struck me as true in adolescence —

the Abyss is always just a step away.

If you stare at anything with burning intensity —

you can see the edge of its bottomless mouth.

Keep looking at it through your tears and sweat,

without turning your gaze even once — soon you will notice nothing else.

The Abyss will tempt you to lean even closer.

Others may think you must have gone blind,

but you know — now you see ever clearer.

You start distinguishing black on black, you start seeing the distant valleys.

Once you manage to really focus,

so that the outside noisy light can’t disturb your full concentration —

then finally you see deep within the Abyss — another Sun,

and stars of another Universe, calling to you with their flickering dance.

Now you may take this final step, one step that still keeps you away.

As you stand on the edge, leaning ever closer to the great expanse — the empty wow of nothing-ness —

you see how the Abyss, with its wrinkled topography of a world alien to comprehension,

rearranges its valleys and mountains — to form your own face.

An artist with major achievements in the realms of music, literature, and visual art, Lera Auerbach has published over 90 compositions in the genres of opera, ballet, symphonic music, and chamber music. In addition to poetry and prose in Russian, she’s contributed to the Best American Poetry blog and writes her own stage libretti. Her 24 Preludes for cello and piano is the basis of Preludes CV, a full-length ballet by the Preludes’ dedicatee, John Neumeier, honoring the 40th anniversary of the Hamburg Ballet. Another ballet, The Little Mermaid, has been performed internationally and will be staged by Neumeier in 2013–2014 for Beijing, Hamburg, and Moscow. Auerbach’s a-cappella opera, The Blind, will be performed in Moscow and New York.

The 24 Preludes, written in 1999, continue a long line of musical tradition, from the Well-Tempered Clavier of Bach through the preludes of Chopin and Debussy to similar cycles by Shostakovich. Ms. Auerbach writes: “Re-establishing the value and expressive possibilities of all major and minor tonalities is as valid at the beginning of the 21st century as it was during Bach’s time, especially if we consider the aesthetics of Western music and its travels in this regard — or disregard — to tonality during the last century. The 24 Preludes follow the circle of fifths, thus covering the entire tonal spectrum.” Musicians start the circle of fifths with the key of C major and its relative minor, A minor, and proceed through the “sharp” keys — G major and E minor, one sharp, D major and B minor, two sharps, etc. — then turn back through the “flat” keys, like G-flat major/E-flat minor, A-flat major/F minor, until we reach F major/D minor and the circle is complete.

About the Preludes, Ms. Auerbach continues:

In writing this work I wished to create a continuum that would allow these short pieces to be united as one single composition. The challenge was not only to write a meaningful and complete prelude that may be only a minute long, but also for this short piece to be an organic part of a larger composition with its own form. Looking at something familiar yet from an unexpected perspective is one of the peculiar characteristics of these pieces — they are often not what they appear to be at first glance. The context and order of preludes is important for their understanding.

Combining lyricism with fierce tonal clashes, the Preludes demand extreme virtuosity from both cellist and pianist. Heard throughout the cycle are the extremes of range: both instruments move from very low to very high registers. There’s an abundance of sonic special effects: for the pianist, tone clusters or thick, cluster-like chords, plus highly complex run passages. The cellist is constantly changing from arco (bowed) playing to pizzicato (plucked) motives and often playing harmonics: faint, echoing tones produced by a finger only partially depressing the string. There are an abundance of glissando passages (sliding through a quick succession of notes) for the cello and frequent directions to play “sul ponticello,” on the bridge, the small piece of wood that separates the bottom of the strings from the resonating body of the instrument. Drawing the bow close to the bridge creates a dry, harsh sound that dramatically contrasts with the smooth tone we’re accustomed to hearing from this instrument.

Each prelude is cast in a traditional key. Many sound quite tonal, while others are tangles of dissonance. They repay repeated hearing as a cycle, especially to hear Auerbach’s fascination with themes constructed on intervals of a minor second (e.g., C to C-sharp) and a seventh (e.g. C to the B-flat or B above). Many of the preludes end quietly, echoing the line from Lera’s poem, Fugue: “the moment of infinite loneliness when sound dies.”

The tempo markings are the best guide to the individual character of the preludes: No. 3 in G major, marked Andante misterioso, ends with haunting microtonal quarter-tone trills in the cello part, and the following No. 4 in E minor, marked Allegro obsessivo, is a perpetual-motion machine. No. 5 in D major begins and ends melodically but turns violent in the middle. No. 8 in F-sharp minor is a soulful, bluesy lament. No. 9 in E major is mostly a cello solo, until low piano octaves appear out of nowhere leading to a fff cluster chord that connects to the next prelude. The tempo marking for No. 10 in C-sharp minor contains the word Sognando (dreaming) it’s an ethereal combination of staccato piano notes with pizzicato cello that creates a very distant sound.

With Prelude No. 12 in G-sharp minor we reach a turning point: the following preludes will take us back through the circle of fifths on the “flat” side. An Adagio, No. 12 starts with an achingly beautiful cello theme, but when it’s repeated it’s played “with a disturbing sound,” the string player seems to be mocking her own song, punctuated by increasingly disquieting undertones from the chromatic piano part.

Prelude No. 13 in G-flat major is for cello alone. The piano starts off No.14 in E-flat minor with the dynamic marking “mp un poco grottesco;” this Allegretto scherzando (joking) turns out to be a sardonic variation on the overture to Mozart’s The Magic Flute. Although No. 16 in B-flat minor is labeled Tempo di Valse, it’s a grotesque little rondo unlike anything from the Viennese waltz kings. With its insistent rhythms, No. 17 in A-flat major seems to lie somewhere between Bartók and the rock band Queen (of Bohemian Rhapsody fame), with the cello sometimes doing an electric guitar impression. Prelude No. 18 in F minor is a more pleasant dance, a pretty, neo-baroque piano tune picked up by the cello. The surging piano runs and loud dynamics of No. 19 in E-flat major explain its Allegro Appassionato indication; No. 20 in C minor likewise lives up to its label, Giocoso (Joking). For No. 21 in B-flat major, titled Dialogo, we have the cello in conversation with itself: the “dialogue” is between the higher and lower registers of the instrument. No. 23 in F major marked Adagio sognando (draming), has the cello playing with a mute, which makes the harmonics even more ethereal than before, and gives them a unique sound. No. 24 in D minor provides a bravura conclusion, Vivo (Lively) with chords and runs constantly building in intensity to a dissonant conclusion marked Grave gandioso e tragico.

Dedicated to cellist David Finckel and pianist Wu Han, Auerbach’s Sonata for violoncello and piano dates from 2002. Auerbach writes,

In this sonata, the piano and violoncello are equal partners. In the dramatic sense, each often plays contrasting roles and expresses different characters. At times, this co-existence is a dialogue, at times a struggle, at times an attempt to resolve inner questions. The piano starts alone with a dark and inescapable statement, full of inner tension. The cello follows — more human, desperate and questioning. The first calling statement of the cello becomes a leitmotif throughout the sonata. The introduction leads to a strange waltz in 5/4 time — as if from the depth of the past, shadows have emerged. The second theme is both dreamy and passionate, and leads to fugal development with its dry twists.

In this first movement, the rather neutral tempo marking of Allegro Moderato belies the emotional intensity of the music. After the short but emphatic opening piano statement and its brief cello reply, a longer piano solo leads us to the main motive, presented by cello alone, followed by that odd waltz, in which both instruments participate. Tempos and meters constantly change. Lyrical cello passages are suddenly interrupted with playing sul ponticello. There’s a cadenza-like passage for cello alone before both instruments eventually play glissandos up to their top registers to bring about a stratospheric conclusion: marked ppp (soft-soft-soft).

The second movement, titled Lament, is more lyrical. Auerbach says, “The juxtaposition of the instruments is also presented in the Adagio of the second movement, where the piano carries a column-like, steady chordal progression, while the cello engages in a lamenting monologue, free and deeply human.” The lyricism contains deep emotions, and the melodic, quasi-D minor tonality is disrupted by sudden dissonances. Once again, the ending is very quiet. The third movement is marked to be played “with obsessive energy.” It features a fast-moving cello part with pounding piano chords and headlong runs. There’s another cadenza-like cello passage, followed by a vast crescendo for both players and an emphatic ending. Ms. Auerbach describes this movement as a toccata “with fiery syncopations.” The final movement is another lament, marked “with extreme intensity.” The composer says:

[This] is perhaps one of the most intense and tragic pieces I have written. It starts on a high emotional point — with the cello playing microtonal trills to evoke the most intense claustrophobic vibrato. The image I had in mind is that of standing at the edge of an abyss, where nothing is left of the past or the future. But, through the darkness a tragedy, inner light emerges. At times, through pain, one may find lost beauty and meaning. At the end, both instruments rise to the height of their registers, as if entering a different kind of existence.

The music of this finale is closely related to the images in the poem Abyss. The microtonal trills, emphasizing quarter-tones, give way to a melody based on half-tones: minor-second intervals. The cello rises to its highest register over cluster-like piano chords; heavy piano octaves then support another passage of microtonal trills. The cello plays guitar-like broken chords and glissandos over an agitated yet quiet piano passage that leads to an eerie ending marked Morendo: Dying Away. The abyss is there, but also light.

The 2004 Postlude, which acts as a kind of commentary on the 24 Preludes, was recorded with prepared piano: altering the instrument’s sound to a distorted, edgy sonority. The Postlude is billed as a variation on Prelude No. 12 in G-sharp minor, and the main cello theme of that prelude is there, along with the staccato piano part, but it all sounds very different now with the changed piano sonority, and the long, dive-bomber glissandos from the cello. It suggests an ancient ruin — whatever civilization Prelude No. 12 originally came from having long since collapsed.

Notes by Andrea Lamoreaux, Music Director for 98.7 WFMT, Chicago’s Classical Experience.

Album Details

Total Time: 75:12

Producer and Engineer: Adam Abeshouse

Recorded: August 7–9, 2012, at The Performing Arts Center, Purchase College, State University of New York

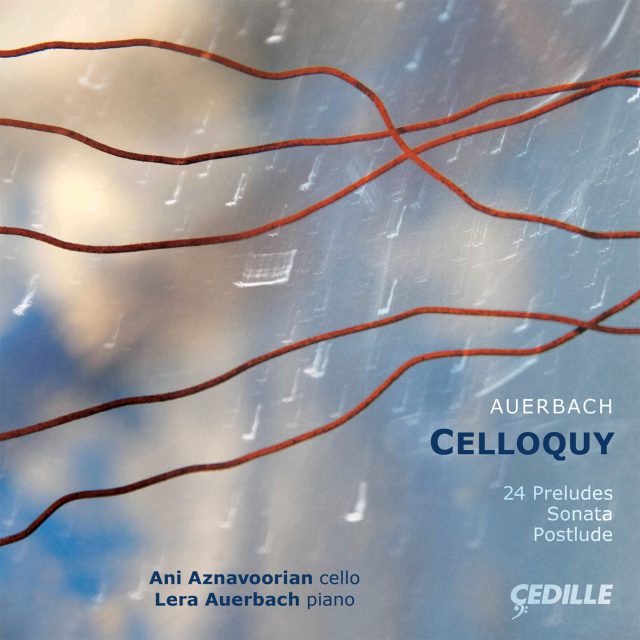

Front Cover Image: (Un)Tangled by Lera Auerbach

Front Cover Titles: Sue Cottrill

Booklet & Inlay Card Design: Nancy Bieschke

Publishers:

24 Preludes for violoncello and piano © 1999 Sikorski (SIK 8508)

Sonata for violoncello and piano © 2002 Sikorski (SIK 8509)

Postlude for violoncello and piano © Sikorski (SIK 8508)

Funded in part by a grant from The Aaron Copland Fund for Music, Inc.

© 2013 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 137