Store

Rarely heard in concert or on disc, 20th-century Mexican composer Carlos Chávez’s spectacular Piano Concerto, completed in 1940, receives an insightful and compelling performance from Mexican-born pianist Jorge Federico Osorio, with his native country’s flagship orchestra, the Orquestra Sinfónica Nacional de Mexico and its music director, the dynamic young conductor Carlos Miguel Prieto.

Chávez (1899–1978) wrote “extraordinarily varied works of Mexican character,” notes Grove Music Online. In addition to Chávez’s epic concerto, Osorio plays three works for solo piano on the new CD: Chávez’s early Meditación; Mexican nationalist composer José Pablo Moncayo’s Muros Verdes (Green Walls), from 1951; and contemporary Mexican-born American composer Samuel Zyman’s Variations on an Original Theme (2010).

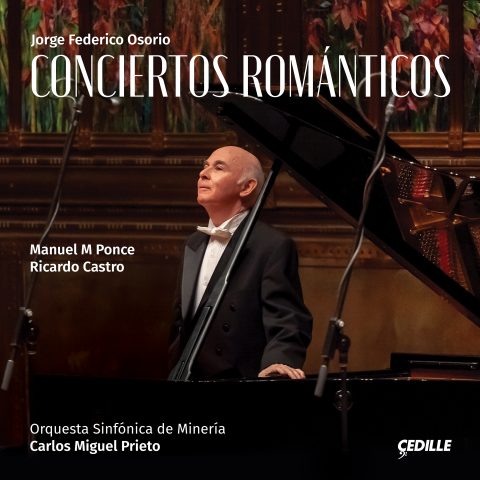

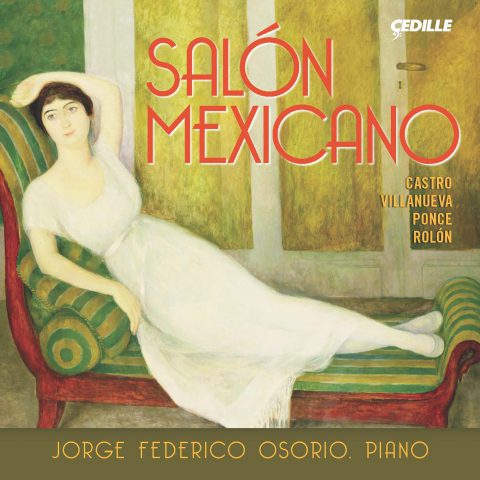

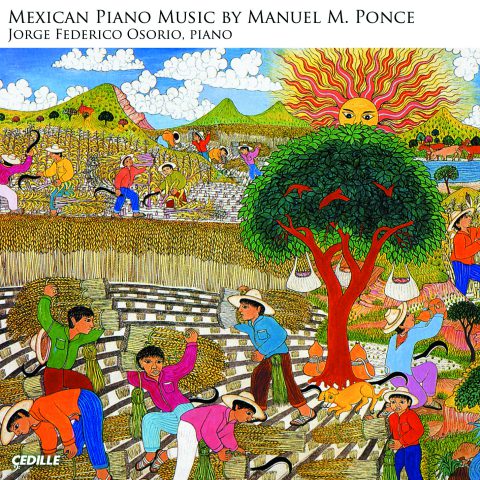

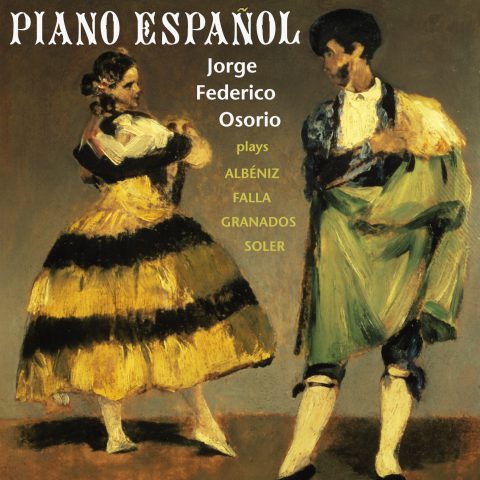

This is Osorio’s fifth recording for Cedille Records. His Cedille label debut, Piano Español, with works by Spanish composers Falla, Albeniz, Soler, and Granados, prompted the Chicago Tribune to declare, “Move over, Alicia de Larrocha.” According to the San Francisco Chronicle, “choosing one highlight over another is impossible in a recording of such sustained excellence.” About.com called Osorio’s Mexican Piano Music by Manuel M. Ponce “a remarkable collection” performed “with clarity and conviction.” Américas magazine enjoyed Osorio’s “warm and insightful reading of these delicate Ponce creations.” The Toronto Star said “Osorio’s playing is faultless” on his Cedille recording of Debussy and Liszt piano works. Fanfare called his 2012 Cedille release, Salón Mexicano, “a delightful recording that confirms Osorio’s outstanding artistry.”

Preview Excerpts

CARLOS CHÁVEZ (1899–1978)

Piano Concerto

JOSÉ PABLO MONCAYO (1912–1958)

SAMUEL ZYMAN (b. 1956)

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletCarlos Chávez Piano Concerto

Notes by Elbio Barilari

Only one composer compares in homeland stature to the larger-than-life image projected by Carlos Chávez (1899–1978), and that is Heitor Villa-Lobos (1887–1959). The Mexican Chávez and Brazilian Villa-Lobos dominated the musical scenes of their respective countries in a way comparable, only, to Wagner in Germany. They were multifaceted individuals with titanic personalities. As composers, conductors, educators, and musical organizers, they also coexisted and compromised with authoritarian political regimes (another similarity to Wagner).

Nobody, of course, denies Villa-Lobos’s and Chávez’s immense creative talent or that they were dedicated to promoting music education and building music institutions that have had a lasting, positive impact on Latin American cultural life. Notwithstanding, both men were polemical personalities whose inheritances are today viewed as a mixture of light and shadow; and so thorough was their musical domination of their countries, that the visibility of other, not-less-talented composers has been blurred and delayed for generations.

With the exception of his lovely Sinfonía India, Chávez’s music — after some years of intense international popularity — has been relatively dormant outside México. Although some of his chamber pieces, such as his Toccata para percussion and Xochipilli have been rescued in recent times by enthusiastic younger ensembles, his other five symphonies and his two monumental concerti — one for violin and the piano concerto on this CD — have been studiously avoided by symphony programmers in the United States (a fate that Villa-Lobos’s music shares).

The two Chávez works included on this album represent quite different moments in his creative life and shed light on his evolution as a composer.

“Meditación”

The solo piano work, Meditación was composed in 1918 and usually receives cursory notice as a romantic, youthful product. A more alert listening reveals that the romantic appearance hides a very original structure. The 19-year-old composer maintains a remarkable musical discourse in which the right and left hands are often independent. The notes may sound romantic but the behavior of both hands is clearly modern.

The piece begins with a short call, beautiful but also unconventional. A quick look at the score shows that, in a counterintuitive way, the phrase starts on the last beat, not the first, of a 4/4 bar. Very soon, the language evolves into what can be described, in 20th-century musical jargon, as two different layers. The right hand plays a motive and reiterates it without developing it as a 19th-century composer would have done. Meanwhile, the left hand plays imaginative rhythmic games, at times opposing the contemplative nature of the themes described by the right hand. It is tempting to think that Chavez, very familiar with the music-play of native Mexicans, attempted to replicate the way in which performers simultaneously play a flute held in the left hand and a drum with the right hand, with a fascinating independence for each line.

Jorge Federico Osorio mentions that “Chávez had a predilection for the low register. When he conducted me during a concert in Brussels, he was very attentive to the low part of the orchestra and demanded that the low instruments needed to be clearly heard.”

Three-quarters of the way into the piece, some echoes of Debussy appear like white clouds in the middle of clear skies. Those echoes function as extrapolations in the musical flow, underscoring even more the idea that we are presented with something more novel and fresh than a youthful meditation produced by someone still under the spell of the prior century.

Far from conspiring against the tightness of the piece, a total of eight modulations in just 58 bars help to create the illusion of a length greater than its five short minutes. By building an expanded psychological time into this delightful piece, the young Chávez accomplished a very mature musical feat.

The work is an early product from a composer who deliberately did not take composition lessons. He did take piano lessons from the great Manuel M. Ponce, but not a single composition class. Chávez did not want to submit to the trends imposed by any teacher — while he did want to be open to all styles and influences, and to make his own artistic choices. At that time, very few composition teachers were available in México, and Chávez considered their doctrines “a weak reflection of French and Italian 19th-century music.” It must be said to say that he was not fully justified in his outright dismissal of such talented and original composers as Candelario Huízar, Julián Carrillo and, especially, Manuel M. Ponce.

By his own choice, Chávez fed from direct sources, voraciously collecting and studying all kinds of scores and manuals in a critical way. Given how doctrinaire and confrontational composition-teaching had become by the first decades of the 20th century, his was probably a wise decision.

Concierto para Piano

The Concierto para piano was commissioned in 1938 by the Guggenheim Foundation. Involved in many other projects and duties, Chávez did not finish the concerto until December 31, 1940. For the premiere, American pianist Eugene List (1918–1985) was the soloist and Dimitri Mitropoulos conducted the New York Philharmonic in Carnegie Hall on January 4, 1942.

The work was subsequently premiered in London, on September 6, with soloist Tom Bromley and Adrian Boult conducting the BBC Orchestra. On August 13, 1943, the concerto was at last heard in México. The great Chilean pianist Claudio Arrau was the soloist and Chávez himself conducted the Sinfónica de México.

This is a work of extreme complexity. Its difficulties for the pianist as well as the orchestra are enormous. 1940s critics loved the piece; The New York Times and Modern Music, among other media, published enthusiastic reviews. Audiences, however, found the piece “cacophonic.”

Cacophony is a feature often present in Chávez’s music. As a modernist composer, Chávez was aware of cacophonies produced by different composers using various techniques since the beginning of the century. He was always up-to-the-minute with different compositional schools and tendencies, and had no empathy for composers who — out of what he termed “laziness” or “provincialism” — where not as alert to new developments. On the other hand, he was extremely vocal in his calls for a Méxican way of using those technical devices; he was aggressive in his diatribes against romantic nostalgias and copycat pieces modeled on trendy creations by European composers.

Chávez’s music is, at once, austere and extraordinarily energetic; cosmopolitan and up-to-date, while being completely and unequivocally Méxican.

The Concierto para piano is a great example of Chávez’s modern nationalistic music that combines local traditions with “universal” resonance — which to him meant, (as it still does today) predominant trends in the metropolies of Europe and New York.

The Concierto is also a magnificent exhibition of the proficiency in composition and orchestration that Chávez had reached in the fourth decade of his life.

The standard procedure still applied by music pundits to Third-World composers — trying to compare us with convenient examples of European or U.S. composers — gives rise to great frustration when applied to Chávez, who is sometimes likened to contemporaries such as Stravinsky, Bartók and Copland.

To begin with, a less superficial analysis may indicate that Copland was more influenced by his friend Chávez (and also by Silvestre Revueltas) than the other way around. Further, the techniques and devices Chávez used were hardly related to those of his Russian and Central European colleagues. Aside from an “ethnic” accent and strong rhythms, similarities are very rare. The non-Western European scales and modes Chávez tends to use come from the Mexican native cultures, not The Rite of Spring or Bartók’s Romanian dances. In a word, Chávez’s rhythms are indeed as “wild” or “exotic” as those of the other composers, but the sources for them can be found in his own country’s indigenous culture.

Chávez’s complexity relies on two concepts — independent layers and abrupt blocks. If we must relate his music to something European, we would depict these as further development of Debussy’s work, which Chávez revered, rather than as a docile “Mexicanization” of Eastern European models.

Chávez was born in México City but he spent his summers and other holidays in Tlaxcala. This highly traditional small town lies in the middle of a heavily native region and feels like a 16th-century community even today. So, Chávez was familiar since childhood with the music he would use as his main source of inspiration.

The concerto’s monumental first movement is an exhaustive sample of Chávez’s mature musical language: sharp angles; strong rhythms; abrupt changes from one block of sound to another, often without any transition or preparation; and the use of native scales, grooves, and timbres — especially the intensive use of percussion and flutes with accents on the piercing sounds of E-flat clarinet and piccolo.

Chávez occasionally quotes indigenous or popular melodies, as in his popular “Obertura republicana” Chapultepec. More often, he uses tradition as a reference but not in a literal way. Rather, he recreates Indian sound-landscapes in a free manner; another trait he shares with his peer, Villa-Lobos.

In this first movement, the sonic tissue is so dense that its is more natural to explain it in terms of textures and layers rather than an as extreme case of contrapuntal complexity. This perception is reinforced by the rhythmic independence of the voices and by the way Chávez uses different sonic “events” and groups of pitches in registers far removed from each other.

The instruments of the orchestra, more than accompanying the piano, seem to be challenging or even fighting against the soloist. At other moments, the piano functions as a voice that is answered, commented on, or contradicted by the community of the orchestra, not unlike the tumultuous music of an indigenous Mexican ritual.

The second movement presents the extremely rare case of a loud adagio. Normally a Molto lento indication, especially after a first movement of devastating power, would prepare the listener for a sweeter mood or at least a melancholic, nostalgically beautiful melody. Chávez, instead, offers a chamber-like sound with the piano striking strong chords on the lower register and the harp echoing those strokes. The double reeds introduce a short theme associated with indigenous sounds. What happens after that is very minimalistic: a skillfully played game between these few elements and a progressive crescendo that dissolves into nothingness without offering the easy relief of a resolution.

Despite its apparently calm title, the last movement, Allegro non troppo, ranges from nervous to frenetic. It is not as demanding in its proportions or instrumental chemistry as the first movement. Even so, its whimsical nature, with passages at breakneck speed, demands a display of uncommon virtuosity which, if realized, will awaken the audience to an ovation that shakes the walls of the most massive orchestral hall.

In his most often-quoted phrase, Chávez asserts: “A masterpiece is an experiment that succeeded, the proof of which only time can provide.” This assertion applies 100 percent to his piano concerto.

Jorge Federico Osorio calls this work, “the most dramatic Mexican concerto.” For this pianist, the gargantuan first movement has a visual quality: “It is like contemplating a mural by Diego Rivera, Rufino Tamayo, or José Clemente Orozco . . . a big work, a big picture also full of small details.”

“The second movement,” Osorio says, “starts almost in a void. Slowly, more sounds start coming, almost like the growing sounds of a volcano, with everything moving toward the eruption in the third movement.”

Osorio approached the concerto for the first time “when I was 15 or 16. After that, I didn’t try again for another 15 years until I finally performed and recorded the work live at the Festival Cervantino with the Sinfónica Nacional.”

Asked if his conception of the piece has changed over the years, Osorio says: “Perhaps my general view of the piece has not changed, but I think my attention to the details has changed. Today I approach this work with more interest in its polyphonic nature, perhaps not so focused on the piano because this is really ‘concertante’ music where the instruments of the orchestra are as important and often as demanding as the part of the soloist.”

Asked what he considers the most remarkable characteristic of the piano concerto, Osorio answers categorically: “¡La energía!”

Muros verdes

José Pablo Moncayo (1912–1958) was exactly what Chávez was not. A loner, very shy, and an outdoors person addicted to mountain-climbing. Trained as a percussionist and also a fine pianist, Moncayo kept a low profile. He is often portrayed by contemporaries as haunting the populous cafés of the Mexican capital quite alone, as though lost in his own thoughts.

This very private individual is also the author of the most popular piece of Mexican classical music: the famous and omnipresent “Huapango,” written in 1941.

Together with Chávez’s “Sinfonía India” and Arturo Márquez’s “Danzon No. 2,” the “Huapango” is one of the three pieces that American orchestras typically program when it seems time to wink at their neglected constituencies of Mexican origin.

Born in Guadalajara in 1912, Moncayo began his music education at the relatively advanced age of 14. After only one year of piano study, he was considered ready to enter the Conservatorio Nacional, where he studied composition, analysis, and orchestration with another luminary of Mexican music, Candelario Huízar (1883–1970) . Moncayo also took composition and conducting with Carlos Chávez, who, despite his refusal to take composition lessons from anyone else, saw no reason to refrain from teaching composition to others.

In 1931, due to Moncayo’s unusual skill at sight-reading, Chávez accepted him for his famous and exclusive composition workshop. By then Moncayo had premiered a composition in a student concert, and had become a member of the percussion section of the Orquesta Sinfónica de México. Soon after, the orchestra hired him as a pianist. Moncayo also worked as a teacher of piano and basic music theory in the public schools.

Over the years, the ubiquitous “Huapango” became a mixed blessing for Moncayo. Thanks to it, he became one of México’s most beloved composers; but also due to it, his other pieces — including a symphony, a sinfonietta, an opera, several major orchestra pieces, and no less interesting chamber, vocal, and piano pieces — have been all but forgotten.

The 1949 symphonic poem Tierra de Temporal the viola sonata (1934), and Muros verdes for solo piano (1951) were the tips of an iceberg: praised and adored by composers, performers, and other informed listeners who knew that Moncayo’s music comprised more than just the “Huapango.” Finally, in 2012, the Mexican Council for Culture and the Arts (CONACULTA) published a remarkable seven-CD set of Moncayo’s complete works, and simultaneously published several books containing all his scores.

Chávez was an influential, proactive, and even generous professor. Several of the most brilliant composers in subsequent generations were, as students, under his care, influence, and personal spell. Chávez’s disciples included among others, Moncayo, Silvestre Revueltas, Blas Galindo, Daniel Ayala, Salvador Contreras and, later, Mario Lavista. Starting in 1942 and thanks to Chávez, several young Mexican musicians, including Moncayo and Galindo, were able to travel to the U.S. and attend the Berkshire Music Festival organized by Aaron Copland and Serge Koussevitkzy.

One can detect or identify elements in Moncayo’s music from his teachers Chávez and Copland. It is more important, however, to see how the composer built his own very strong and original musical personality. Like Chávez, Moncayo is a vigorously rhythmic composer; but he comes up with his own rhythmic devices, such as his beloved 5/8 grooves, or his series of quadruples superimposed on 3/4, 6/8 or even 5/8 time-signatures. His favorite structural form is a spiral: a succession of expositions and recapitulations interwoven in a manner unique to Moncayo.

Like Chávez, Moncayo can be anti-romantic, angular, mechanical, and even “scientific,” but he also can jump into a folkloric melody or invent a haunting theme among the most beautiful produced by a mid-20th-century composer — in México or anywhere.

In short, Moncayo is a major composer who reached popular fame through his “Huapango” but still awaits a richly deserved recognition for the other, more interesting part of his work.

Muros verdes or “Green Walls,” was composed in 1951. The title relates to a park and forest preserve in México City known as Viveros de Coyoacán. A lover of nature, green spaces, and open horizons, the composer liked to take long walks in the Viveros. The piece is dedicated to his second wife, Clarita, formerly one of his harmony students.

Wrongly analyzed as an example of late impressionistic writing, the work constitutes, instead, an original experiment — a successful one, as Chávez would say — in Moncayo’s composition techniques.

The piece unfolds in four parts, each with very specific characteristics but “mysteriously” attached to the other. The last part is as long as the first three combined, which is typical of Moncayo’s taste for symmetries, mathematical proportions, and other formal resources of a speculative nature.

The composer opens Muros verdes with an abundance of soft thirds that evolve to a more crisp language with the fourth as the predominant interval. In western, music the mention of fourths immediately evokes Paul Hindemith. Moncayo’s fourths, however, don’t sound “Hindemithian” but rather anticipate, by more than a decade, the jazz-piano language of McCoy Tyner, Herbie Hancock, and Chick Corea. Moncayo’s modal scales (often pentatonic scales of native-Mexican origin) and “suspended” chords in this 1951 piece prefigure the modal jazz of the 1960s and 70s.

Osorio has paid periodical visits to Muros verdes since his 20s. His mother and only piano teacher, Luz María Puente, now in her 90s, also continues to play Moncayo’s delightful work.

As Osorio plays fragments of Muros verdes in one of the two pianos that inhabit his livingroom not far from Chicago, he describes the various sections of the piece with adjectives like “crystalline” and “diaphanous.” As the piece progresses from a beginning that Osorio considers “almost naïve” to the most intricate regions of the fourth section, the changes in the pianist’s facial expressions reflect the inner tensions built into the piece — as Osorio were discovering for the first time the musical loveliness that Moncayo gradually reveals in this short piece, like a jewel-box full of hidden gems.

Album Details

Total Time: 64:50

Producer: Bogdan Zawistowski

Engineers: Humberto Terán & Bogdan Zawistowski

Recorded: March 7–9, 2011 Sala Nezahualcóyotl, Centro Cultural Universitario UNAM, Mexico, D.F.

Steinway Piano

Solo Works

Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineer: Bill Maylone Fay and Daniel Levin Performance Studio at 98.7 WFMT, Chicago

Recorded: October 24–25, 2012

Steinway Piano Technician: Ken Orgel

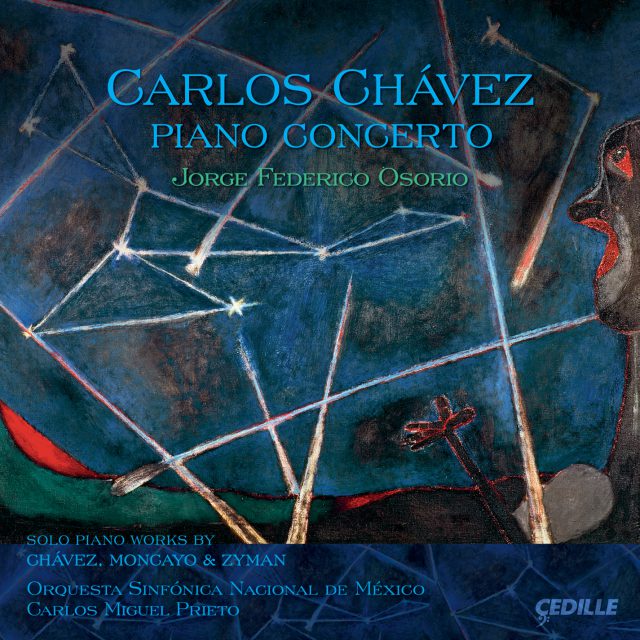

Cover Art: Heavenly Bodies, 1946. Oil with sand on canvas, 34 x 41 3/8 inches (86.3 x 105 cm). The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice 76.2553.119. © Tamayo Heirs/Mexico/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Cover Design: Sue Cottrill

Publishers: Chávez Piano Concerto ©1938 G. Schirmer Inc.; Moncayo Muros Verdes ©1964 Ediciones Mexicana de música, A.C.; Zyman Variations on an Original Theme ©2010 Merion Music, Inc. (Theodore Presser Company, Sole Representative).

© 2013 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 140