Store

Violinist Rachel Barton Pine, “an exciting, boundary-defying performer” (Washington Post) known for her “bravura technique and soulful musicianship” (New York Times), headlines a groundbreaking album of blues-influenced classical works for solo violin and violin and piano by 20th and 21st century composers of African descent.

World-premiere recordings include Noel Da Costa’s A Set of Dance Tunes for Solo Violin, based on American fiddle tunes, and Billy Childs’s Incident on Larpenteur Avenue, a single-movement violin sonata/tone poem written as a response to a fatal shooting by police. Another premiere is Wendell Logan’s violin and piano arrangement of Duke Ellington’s 1935 composition, In a Sentimental Mood.

The album’s title track, Dolores White’s improvisational Blues Dialogues, draws on classical, jazz, and country music, as well as African-American vocalizations and a blues harmonic language. David N. Baker’s gospel-tinged Blues (Deliver My Soul) evokes the ecstatic energy of a Black church service. Coleridge-Taylor Perkinson’s Blue/s Forms and Louisiana Blues Strut befit a composer with a legacy of achievements in the classical, jazz, modern dance, and pop music worlds. Each movement of William Grant Still’s Suite for Violin and Piano evokes the work of a different African-American visual artist. Clarence Cameron White’s Levee Dance, a favorite of legendary violinist Jascha Heifetz, surrounds a traditional African-American spiritual with a playful, syncopated dance. Errollyn Wallen’s Woogie Boogie is a humorous and inventive reimaging of the boogie-woogie blues dance. Daniel Bernard Roumain’s Filter, with a new opening cadenza written specially for Rachel Barton Pine, conjures the sounds of electronic dance music and psychedelic guitar. Concluding the program, Charles S. Brown’s A Song Without Words was inspired by bottleneck guitar player and gospel blues master Blind Willie Johnson.

Listen to Jim Ginsburg’s interview

with Rachel Barton Pine on Cedille’s

Classical Chicago Podcast

Preview Excerpts

DAVID N. BAKER (1931–2016)

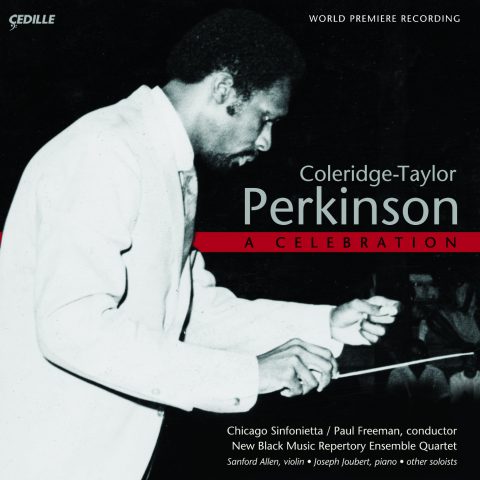

COLERIDGE-TAYLOR PERKINSON (1932–2004)

Blue/s Forms for solo violin

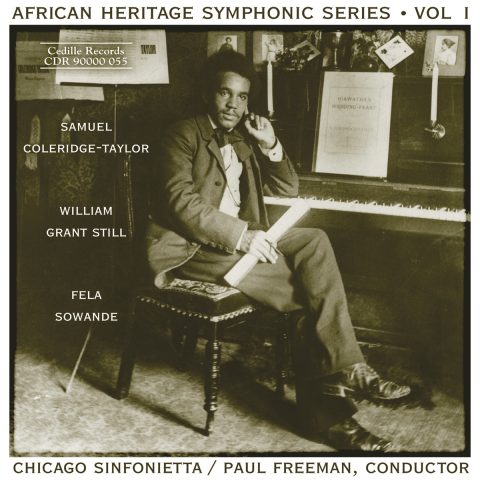

WILLIAM GRANT STILL (1895–1978)

Suite for Violin and Piano

NOEL DA COSTA (1929–2002)

A Set of Dance Tunes for Solo Violin

CLARENCE CAMERON WHITE (1880–1960)

DUKE ELLINGTON (1899–1974), ARR. WENDELL LOGAN

DOLORES WHITE (b. 1932)

Blues Dialogues for solo violin

ERROLLYN WALLEN (b. 1958)

BILLY CHILDS (b. 1957)

DANIEL BERNARD ROUMAIN (b. 1977)

CHARLES S. BROWN (b. 1940)

WILLIAM GRANT STILL, ARR. LOUIS KAUFMAN

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletThe Freedom Call of the Blues

Notes by Mark Clague

THE FREEDOM CALL OF THE BLUES

To sing the blues is to say something. It may be a cry of personal pain, a celebration of community hope, or a scream of human injustice. The blues is about relationships, typically between the self and the world, but often as not with a symbolic resonance that argues for the universal. The blues is about struggle. It is a music born of the Deep South after the U.S. Civil War, created by the sons, and a few daughters, of enslaved African-Americans. Often the blues accompanied sharecropping in the Mississippi Delta — a practice of farming leased land that was essentially a new form of permanent, indentured servitude by Black bodies to White masters. The blues draws expression from their work songs and field hollers, hopes and trials, spirituals, chants, shouts, and narrative ballads. It is a secular music with a sacred charge to amplify the voice of freedom, to celebrate the expression of those previously denied the right to speak. It is a music of passion, perseverance, resilience, hope, and joy. While having the blues is to feel the weighted veil of sadness, even depression; to perform the blues is to fight back against the shadows. To sing the blues is to triumph.

The blues is a process of working things out. Blues lyrics typically tell a story. Its classic poetic form — often analyzed with the symbols AAB — is inherently a dialogue: statement, restatement, response. The artist grapples with life and takes action. The blues is thus less a formal model than an expressive practice — an art of understanding to inspire change. It may often have 12-bars with a three-fold cyclic pattern of four chords (I-I-I-I•IV-IV-I-I•V-IV-I-I), but it is not a genre born of textbook descriptions. It is the raw, direct expression of the individual, most idiomatically a singer with a guitar. There are infinite types of blues, beginning in the American South with Delta and Piedmont Blues but extending geographically in space, place, and time. There are honky-tonk blues, country blues, urban blues, and electric blues. Louisiana blues, Kansas City blues, Chicago blues, and West Coast blues. Gospel blues and hokum blues. Acid blues, blues rock, boogie-woogie, rhythm and blues, punk blues, and hip hop. There are even blues in classical music, a symphonic form pioneered by George Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue (1924), William Grant Still’s Afro-American Symphony (1930), and Duke Ellington’s Diminuendo and Crescendo in Blue (1937).

Rachel Barton Pine’s Blues Dialogues explores the expressive power of the blues, its history and future directions. Each track draws strength from the tradition of Robert Johnson, Memphis Minnie, Blind Willie Johnson, and Bessie Smith. Yet rather than rehearse the conventional 12-bar blues progression, the composers featured here find inspiration in the freedom of the blues. Ever changing meters and continuous musical transformation convey a living, organic sense of the blues as a vital engagement with the world. There are quotes of American fiddle tunes, gospel hymns and spirituals, upbeat boogie-woogie dance tunes, sonic references to the signal processing of electronic dance music, repairs offered to the racist traditions of minstrelsy, and screams of anger, frustration, and despair at the killing of Black Americans by those charged to protect them. Each composer draws from the cultural tributaries of the African Diaspora, and each has come to terms with the power of this heritage to forge an utterly personal expression of universal community across time, place, and people. Dialoguing with the blues is thus to enact a prayer of possibility and of hope — whether given voice by a singer, an electric guitar, or on the strings of a violin.

BLUES (DELIVER MY SOUL) (1968)

DAVID N. BAKER

David Nathaniel Baker (1931–2016) expanded the role of the composer as a voice of African-American music history. Originally a jazz trombonist and recording artist, an injury prompted his switch to the cello and the move toward composition and education. A pioneering theorist of jazz, Baker had a lasting impact on jazz pedagogy and shaped the Jazz Studies Department at Indiana University (Bloomington) where he taught for some 50 years. Often labeled a “Third Stream” composer who mixed jazz and classical musics, Baker is more accurately described as an artist who traversed the stylistic continuum from improvisation through the symphony and all styles between. Adapting “Deliver My Soul” for violin and piano from his Psalm 22 for chorus, Baker created a gospel-blues hybrid, idiomatic to the violin and deeply rooted in the blues form and style. The virtuoso opening cadenza introduces a rich, full-chorded gospel-tinged melody that grows into an ecstatic, accelerating shout, recalling the power of a Black church service. Harmonically, Baker adapts classic 12-bar blues harmonies into a three-part 24-bar structure (3×8 bars) in triple meter. The work closes with a reprise of the opening theme plus a bluesy coda.

BLUE/S FORMS (1972)

COLERIDGE-TAYLOR PERKINSON

Named in homage to the Afro-British composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (1875–1912), Coleridge-Taylor Perkinson (1932–2004) was a characteristically American Renaissance musician who worked creatively across multiple genres and styles. Born and trained in New York City while later moving to Chicago, he made a living by teaching at Brooklyn College, composing classical music, conducting orchestras (he co-founded the Symphony of the New World), playing piano in jazz drummer Max Roach’s quartet, serving as music director for choreographers including Jerome Robbins and Alvin Ailey, writing arrangements for popular singers such as Marvin Gaye and Harry Belafonte, and composing film and television scores. Blue/s Forms similarly traverses popular and classical impulses. It is deeply connected to its dedicatee — Sanford Allen (b. 1939), the New York Philharmonic’s first full-time African-American violinist, active from 1962 to 1977. (Not coincidentally, Allen made the work’s debut recording on the 2004 Cedille album Coleridge-Taylor Perkinson: A Celebration.) Written in the key of G to take advantage of the lowest open string on the violin, the work has no key signature but shifts freely between major and minor. This ambiguity draws upon the expressive harmonic blurring of “blue notes” that fall between the cracks of the Western European tempered scale, between major and minor harmonies. The opening gesture of Movement I, Plain Blue/s, for example, features the pitches G and D with an A-sharp sliding to a B natural. Thus, an opening G minor chord morphs into G major as B-flat / A-sharp becomes B natural. This gesture repeats four times, is interrupted by a contrasting triplet segment, and returns twice again. Movement II, Just Blue/s taps into the feelings of sadness typically associated with blues music. Played freely with a mute, the movement is unified by an upward sighing motivic gesture — a short note decorated by a grace note followed by a longer tone. Movement III, Jettin’ Blue/s is a jazzy, chromatic jig with shifting asymmetrical meters that keep the syncopation of its perpetual 16th-note patter ever off balance.

LOUISIANA BLUES STRUT (2001)

COLERIDGE-TAYLOR PERKINSON

Although written 29 years later, Louisiana Blues Strut was originally envisioned as a fourth movement to Blue/s Forms. Instead, the music took a different compositional turn. Subtitled “A Cakewalk,” its rhythmically driving slides depict the strutting and preening of the ironic plantation dance in which Black couples mock the pretension of Whites by imitating the grand march of their “Big House” society balls. Perkinson’s driving rhythms within an ever-shifting metric feel nevertheless create a bouncing syncopation and bring the cakewalk’s humor to the fore.

SUITE FOR VIOLIN AND PIANO (1943)

WILLIAM GRANT STILL

For composer William Grant Still (1895–1978), the blues assert a distinct ethos of Black America — a proud spirit of beliefs and aspirations. Guided by the intellectual and artistic optimism of the Harlem Renaissance, Still celebrated this spirit of African-inspired creativity, but since indigenous African music was all-but-unknown in the United States at the time, Still took inspiration from the Black American writers, poets, painters, and sculptors of the era. Together, they sought to instill Black pride by imagining the conceptual, unifying power of “Africa” in their heritage. Following upon such works as the Afro-American Symphony (1930) and choral ballet Sahdji (1931), Still wrote the Suite for Violin and Piano (1943). It was composed for a husband-and-wife duo — violinist Louis Kaufman and pianist Annette Kaufman — after the inspiration of three African-American visual artists. Movement I is a response to the entranced kinetics of “African Dancer,” a 1933 plaster sculpture by Richmond Barthé (1901–1989). Its “majestic” opening piano fanfare evokes African drumming while highlighting the expressive tension between lyricism and rhythm in the violin’s quickening athleticisms. A languid 4/4 slow blues section alternates with the fast triple-time dance, yet the chromaticisms of the blues can be heard throughout. Movement II is inspired by the California-based artist Sargent Johnson (1888–1967), specifically a work titled “Mother and Child” that he realized in both sculpture and lithography in the 1930s. Its imagery focuses on a monumental Black female figure being hugged by a child. This infinite expression of acceptance, comfort, and love conveys Johnson’s goal: “to show the natural beauty and dignity” of the “American Negro” in a universal human gesture. The composer conveys this same bond musically, using a neighbor-note figure, as the melody alternates back and forth between a pair of two notes that thus become one. This simplest of motifs is emblematic of the movement as a whole as the melodic gesture (set as a triplet plus a long note) expands to wider intervals in a turbulent middle section and then returns to its original stepwise form that climaxes in a soaring lyricism. “Gamin,” by sculptor Augusta Savage (1892–1962), gives Movement III its title. The bust depicts a young African-American boy glancing askew. The title is a French term for a “kid” or street urchin. Savage’s work conveys a spirit of irrepressible optimism, energy, and wise-beyond-its-years determination that Still captures in the boogie-woogie eighth notes of the piano and the syncopated bluesy dance of the violin.

A SET OF DANCE TUNES FOR SOLO VIOLIN (1968)

NOEL DA COSTA

Born in Lagos, Nigeria to Salvation Army missionaries from Kingston, Jamaica, Noel Da Costa (1929–2002) moved from the West Indies to New York City at age 11 and grew up in Harlem. The sonic kaleidoscope of New York — in the streets, in church, in the concert hall, and on the radio — shaped his polystylistic musical imagination. The composer even felt that his childhood experiences in Africa and the West Indies provided an “unconscious memory” of indigenous “snatches, motives and patterns” that appeared in his compositions. In 1968, however, Da Costa turned to an unexpected source for inspiration, arranging and transforming five American fiddle tunes as A Set of Dance Tunes for Solo Violin. The source melodies were likely found in William Bradbury Ryan’s 1883 Mammoth Collection, a book containing more than 1000 reels, jigs, hornpipes, clogs, walk-arounds, and other dances. Da Costa translates the core pitches, rhythms, and accents of each tune faithfully, but enriches their harmonies and adjusts the shape of each tune with new slurs, dynamics, and octave shifts. After the tune has sounded in full, Da Costa frequently extends the melody with original elaborations in a parallel stylistic vein. “Brudder Bones” is a walk-around for a minstrel show cakewalk. The quoted melody appears as the opening 17-bar “slow march” and then as the first eight bars of the faster “Dance.” Both tunes return to close the movement after a “Free (improvisational)” interlude.

Da Costa imitates the rondo-like form of “Neumedia” with its three distinct themes, but uses octave shifts and embellishments to vary — if not fully disguise — their repetitions. The melody of “Little Diamond Jig” opens the third movement, while the “Bird on the Wing Jig” tune enters after the fermata. The opening jig later returns in abstracted form to close the medley. Movements Four and Five form a pair through the use of the same clog dance tune, titled “New Orleans (Lancashire)” in Ryan’s collection. Movement Four presents the whimsical, lilting melody in full. A faster contrasting section intervenes, until the first four bars of the lilting theme return to close. This clear statement of the musical theme serves to introduce Da Costa’s most transformative writing of the set; in Movement Five, the composer offers a full-blown blues reinterpretation of the traditional clog melody, now slower and grittier, while expressing feelings that are in turn poignant, intense, and tender.

LEVEE DANCE, OP. 26, NO. 2 (1927)

CLARENCE CAMERON WHITE

Championed by violin virtuoso Jascha Heifetz in recording and recital, Levee Dance (1927) was written by the Tennessee-born violinist and composer Clarence Cameron White (1880–1960). White was a founding member of the National Association of Negro Musicians (est. 1919) and later served as its president. (Rachel Barton Pine is a proud life member of the Chicago Music Association — NANM’s first and founding branch — and her 2016 recital for the organization helped inspire this album.) White’s compositions characteristically evoke Black identity, often by quoting spirituals. The commanding and powerful melody of “Go Down Moses,” for example, forms the central episode of Levee Dance. On the surface, this traditional African-American spiritual tells of Moses’s demand to the Egyptian Pharaohs to “Let My People Go.” However, its call for freedom had resonance for all oppressed peoples and especially the enslaved people of the United States who created the song as a covert form of protest in the guise of faithful worship. The composer frames the traditional melody with a syncopated dance in which a rising F-major phrase lands on a playful alternation of major and minor thirds (A and A-flat), bringing out a blue-note chromaticism that features prominently throughout the piece. Virtuoso gestures of technique and range, plus a solo cadenza made Levee Dance one of Heifetz’s favorite encores. No recording of White seems to have survived. Given the composer’s high stature and musical attainment, it is likely that the racial bias of the time prevented him from recording this composition, as well as others.

IN A SENTIMENTAL MOOD (1935/1988)

DUKE ELLINGTON

ARR. WENDELL LOGAN

Wendall Logan (1940–2010) was inspired to pursue composition after hearing Igor Stravinsky’s Firebird Suite. It is little surprise, then, that mixing old with new, exploring instrumental color, and experimenting with form and performance technique became his stylistic hallmarks. His violin and piano realization of Duke Ellington’s (1899–1974) blissful ballad, “In a Sentimental Mood,” speaks to Logan’s long experience as both a jazz and concert music composer. It fuses the sophisticated artistic aspirations of Ellington’s 32-bar song with 20th-century experiments in concert music. Logan’s rendition embellishes, using the violin’s idiomatic virtuosity in range, gesture, and color to convey the song’s dreamy love lyric, yet never loses touch with Ellington’s tune. An opening piano fanfare and violin cadenza invite a sotto voce introduction of the melody’s initial A section. When the pianist reaches into the instrument to pluck its strings, it imitates the pizzicato line of a jazz double bass. Like the tune, Logan’s arrangement is here delicate, “strange and sweet.” A fuller repetition of the melody’s A section, highlighting Ellington’s rich harmonies, follows and leads to a flowing, songful presentation of the melody’s contrasting bridge or B section. The opening title-phrase soon returns and rises through the words “in a sentimental mood” to complete the music’s journey through the AABA form. A brief coda, realized sul ponticello, leads to wistful recollections of the melodic motto to end in a dreamlike reverie. The arrangement’s sheer variety disguises how the entire performance presents just a single journey through Ellington’s tune.

BLUES DIALOGUES (1988/2016)

DOLORES WHITE

Dolores White’s (b. 1932) Blues Dialogues for solo violin gives Rachel Barton Pine’s recording project its title and its inspiration. White’s own inspiration was hearing her son perform Coleridge-Taylor Perkinson’s Blue/s Forms on his Master’s Degree Recital at Boston University. White explained in an email that the work is based in “African-American vocalizations and harmonic language rooted historically in the blues as both a genre and culture.” In the style of an improvisation, the music largely avoids verbatim repetition and instead unfolds as a free-flowing conversation or dialogue. With frequently changing meters, its rhythms escape predictability to enhance this sense of improvisation. White’s musical language is classically based with influences from “jazz and country music,” forging a distinctive combination of her “adored composers” — models including “Béla Bartók, Igor Stravinsky, Elliott Carter, Alberto Ginastera, and Thelonious Monk.” Written in 1988 as the first in a set of three movements, “Blues feeling” evokes its performance direction as virtuoso vocalisms filter through evolving harmonic mutations, chromaticism, and blue notes. Its opening section ends with a stunning tritone double-stop glissando. Movement II, marked “Expressive / Improvisatory,” offers a contrasting “laid back,” “bluesy feel.” Muted sighing gestures express a blues melancholy, with fortissimo and rapid-fire outbursts that seem to struggle against a haze of depression. “Fast and Funky” is a short, excited interjection with a jazzy triplet swing that sets up the concluding movement, “Moderately fast.” White decided to add this new movement in 2016 because she felt the original three-movement piece was incomplete and needed a fourth movement that exhibited a full bravura sound and technique across both genres (classical and blues). It features a rollicking 4/4 dance in blues form that bookends a freeform contrasting interlude of brief virtuoso episodes. One such episode briefly paraphrases the first movement of Bartók’s 1944 Sonata for Solo Violin, helping to exemplify how this fourth and concluding dialogue is propelled by the composer’s imaginative sense of ever-developing variation and exploration.

WOOGIE BOOGIE (1999)

ERROLLYN WALLEN

Woogie Boogie, by the Belize-born British composer Errollyn Wallen (b. 1958), updates boogie-woogie piano stylings for the classical violin. A composer who crosses boundaries between classical and popular musics, Wallen captures the spirited energy of this traditional African-American genre while thoroughly, and humorously, departing from its conventions. Although the piece is not in 12-bar blues form, nor in predictable 4/4 time, boogie-woogie’s characteristic “eight to the bar” left-hand bass line with its continuous stream of driving eighth-note energy is clearly felt in both the violin and piano of Wallen’s composition. The resulting rhythmic interplay creates a rock ’n’ roll feel, updating the traditional genre to a more modern popular music style. Commissioned by Faber Music for its Unbeaten Tracks Series, Woogie Boogie has been featured as an examination piece for the Associated Board of the Royal Schools of Music. Its rhythmic displacements, empty downbeats, and the playful contrapuntal interaction of the two instruments make extraordinary demands upon the performers’ sense of pulse and rhythmic accuracy, while its singing melodies, dynamic shifts, and ever-changing accents test the violinist’s musicality.

FILTER (1992, WITH NEW CADENZA 2018)

DANIEL BERNARD ROUMAIN

With Filter, violinist and composer Daniel Bernard Roumain (b. 1970) conjures the sound world of hip hop and electronic dance music on the acoustic violin. While spinning blistering virtuosic patterns, the performer is asked to “filter” the violin’s coloring by moving the bow “as close to, and as far away from, the bridge as possible.” This technique morphs the tone colors of the instrument by emphasizing different partials of each vibrating string to bring out the high trebles or resonant lows of the overtone series. The composer states that the “effect should emulate a high-/low-pass filter found on most DJ consoles.” Each performance of Filter is thus unique as the player “filters” her sound improvisationally. This recording features the premiere of an added opening cadenza that Rachel Barton Pine requested from the composer. Titled “Hollerin’ in the night…” and featuring the blues scale, it foreshadows the original composition and is meant to evoke the psychedelic blues stylings of electric guitarist Jimi Hendrix — a musician similarly fascinated by the transformation of noise into musical expression. In Hendrix’s case, this meant the expressive use of the peals and shrieks of amplified electronic feedback.

INCIDENT ON LARPENTEUR AVENUE (2018)

BILLY CHILDS

Commissioned by Rachel Barton Pine specially for this album, Billy Childs’ (b. 1957) Incident on Larpenteur Avenue is a single-movement violin sonata as tone poem that explores the events and impact of the 2016 killing of Philando Castile by a Minnesota police officer. Castile’s girlfriend, Diamond Reynolds, live-streamed the shooting’s aftermath on social media as her mortally injured partner lay slumped over in the driver’s seat, bloody and moaning. Officer Jeronimo Yanez was charged with manslaughter but was later acquitted. “Castile’s murder affected me deeply,” the composer wrote in an email, “and filled me with a sense of rage and sadness. The composing process was very cathartic for me and helped me to clarify my feelings about the horrible incident.”

The beautiful dread of the spinning violin melody that opens Childs’ musical vision is destabilized by the foreboding of the piano’s metrically unstable running 16th-note accompaniment: “It is haunting, unsettling, an omen of bad things to come,” explains the composer. The violin soon adopts this agitated 16th-note passagework as the tension rises, leading to a descending run that crashes to a halt on a fortississimo augmented seventh chord with an added sharp ninth. It is here that the events of video are depicted. Seven additional augmented chords echo the seven fatal gunshots fired at Castile. The composer hears these chordal strikes as a dissonant polychordal combination of “C-sharp and D minor” with missing tones. The violin’s snap pizzicatti mimic the piercing shots, while representing the shock of victim, officer, and girlfriend alike. A stunned hymn-like adagio follows with the piano’s soft chording highlighting angry exclamations from the violin. “The violin bursts are from the point of view of Diamond Reynolds, while the piano represents Philando Castile’s life slipping away,” explains the composer. Sadness sets in as the violin soon joins the hymn, culminating in descending tremolo chords. “Musically, I was thinking of Rachmaninov’s Prelude in C-sharp minor,” Childs reports. A “plaintive,” baroque-like “lament” melody emerges, again featuring outbursts of anger that inspire a recapitulation of the turbulent music of the work’s opening. Episodes of struggle interrupt, and the work ends with a final, ambiguous fading away of the violin’s atmospheric cry — unanswered and unresolved.

“The recapitulation reveals that this incident is continuing. This is happening somewhere else in our world,” explains Childs. Incident, in Childs’ mind, serves as a political statement, simultaneously demanding justice while proclaiming an essential humanity. Childs explains that his message is not direct: “Mine is not a controlled message. I want people to be moved by it: for it to create a dramatic impact. If that experience makes them look at the world differently, that’s the goal. Basically, I want people to feel.” While Childs composed Incident without any reference to or direct inspiration from the blues, his use of narrative parallels the blues tradition of telling one’s story as a form of protest. Incident on Larpenteur Avenue, like the blues, is a meditation on real events; it is about trying to gain a deeper understanding.

A SONG WITHOUT WORDS (1974)

CHARLES S. BROWN

A Song without Words was inspired by the singing of evangelist, bottleneck slide guitarist, and gospel blues master Blind Willie Johnson (1897–1945). Johnson recorded 30 influential sides in three short years (1927–1930) for Columbia Records. His debut recording was so popular that it outsold a concurrent release by reigning blues queen Bessie Smith. Composer Charles S. Brown (b. 1940) was born in Marianna, Arkansas (not far from Pendleton, Texas where Johnson was born), but grew up in Detroit, where he was mentored by the influential choir director Brazeal Dennard. Brown composed his lyric-less song after hearing Johnson’s iconic recording “Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground,” influenced by the bluesman’s atmospheric bottleneck slide guitar playing and spiritual, non-texted humming. Typically performed by solo voice and piano, Brown’s homage calls for a wordless, improvised vocalise, here artfully realized on the violin. Bow on strings becomes the analog of breath through vocal chords, evoking Johnson’s nuanced expressive slides, ghosted notes, and subtle colorations. Brown studied with folklorist Willis L. James at Morehouse College and tenor John McCollum at the University of Michigan (B.M. 1974, M.M. 1975). A voice teacher and professional choral singer, the composer writes most frequently for solo and choral voice and has taught at Missouri’s Lincoln University, Borough of Manhattan Community College, and in the New York City Public School system.

(Available Digitally)

“BLUES” FROM LENOX AVENUE FOR VIOLIN AND PIANO (1937)

WILLIAM GRANT STILL, ARR. LOUIS KAUFMAN

New York City’s Lenox Avenue runs from the north gate of Central Park up to 149th Street in Manhattan. In the 1930s, especially, the heartbeat of African-American culture pulsed through Lenox Avenue. The street served as the social and cultural artery of Harlem and its artistic renaissance. Commissioned by CBS Radio in 1936, William Grant Still’s Lenox Avenue is a 25-minute radio show (and later a ballet) with a scenario by Verna Arvey, scored for narrator, chorus, piano, and orchestra. It tells the story of a visitor to the neighborhood with a dollar to spend in sampling the avenue’s many sounds and ideas. The visitor is paralyzed by Harlem’s many choices of musical delights. He wanders between Club Creole (jazz), the Haven of Rest Mission (spirituals), and an apartment house (blues). It is here that the strains of a languid piano blues melody in 12/8 time escape a rent party. The visitor is seduced by the music and tempted to enter by the flirtations of a sensuous solo dancer seen at a window. “Blues” from Lenox Avenue for violin and piano is an almost note-for-note transcription of this rent party music, arranged by the composer’s friend Louis Kaufman — the violinist for whom Still wrote his 1943 Suite for Violin and Piano.

Mark Clague is Associate Professor of Musicology, American Culture, and African American Studies at the University of Michigan and serves as Chief Advisor to the Rachel Barton Pine Foundation’s Music by Black Composers project. He also wrote the extensive program notes for Pine’s 1997 Cedille album, Violin Concertos by Black Composers of the 18th & 19th Centuries.

Album Details

Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineer: Bill Maylone

Editing: Jeanne Velonis

Cover Photo: Lisa-Marie Mazzucco

Graphic Design: Bark Design

Recorded: December 18-22, 2017 and May 4, 2018 at Nichols Hall, Music Institute of Chicago, Evanston, IL

©2018 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 182