Store

Store

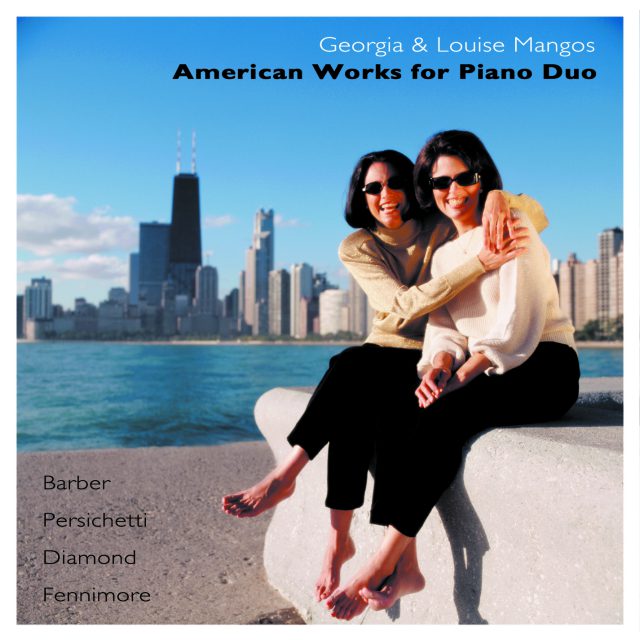

American Works for Piano Duo

The five pieces on this disc — all original works for two pianos or piano duet — sound distinctly American. While this statement is undeniable, it begs the question: What constitutes a distinctly American sound? The composers represented here employ very different compositional styles and harmonic languages. How then can they all be uniquely “American” in their sound?

The two pieces whose American-ness are easiest to explicate are Samuel Barber’s Souvenirs, Op. 28 and Joseph Fennimore’s Crystal Stairs. Both have unmistakable roots in the quintessential American city, New York. In the preface to G. Schirmer’s 1954 publication of his piece, Barber wrote: “One might imagine a divertissement in a setting of the Palm Court of the Hotel Plaza in New York….” Souvenirs bubbles with an energy and glamour that immediately conjure the bright lights of the big city. Although the six dances that make up Souvenirs have an international flair (right down to their titles), they all share a cosmopolitan feel, for everything has been filtered through New York’s eyes and ears.

Joseph Fennimore readily admits the influence of pop and Broadway on his music. From the opening measures of Crystal Stairs, one feels a Busby Berkeley production is about to begin. The raw energy of its initial explosion of sound is just what we expect to hear in a big budget Broadway production. And Crystal Stairs does not disappoint. It is a true musical extravaganza with massive chordal sections, exploitation of registers, jazzy syncopations, and convulsing rhythms. Listening to the piano duet version on this disc, it is often hard to believe (and easy to forget) that all this sound is coming from a single piano.

The two Persichetti works offer a very different, but equally “American” sound. Whereas Barber and Fennimore — in the pieces heard here at least — convey the more public American sonority of Broadway and Fifth Avenue, Persichetti presents a more personal American voice. Those lucky enough to have met Persichetti invariably came away impressed by his elegant charm and unpretentious manner. He unabashedly conveyed the delight he took in performing his music (he wrote the Concerto for Piano Four-Hands, Op. 56 for himself and his future wife Dorothea Flannigan) and at hearing his works performed by others. With his legendary skill, Persichetti fused these endearing personal qualities in his music: for example, in the suave urbanity of his long lyrical melodies and in the joyous rhythmic energy with which both works heard here abound. Persichetti used our 20th- century musical vocabulary to make us listen in a fresh way. Precise attacks, motor rhythms, changing meters, syncopations, and dissonance are all typical 20th-century devices. But they sound so fresh when they are not employed as the means to an end. Dissonance is heard as an emotionally powerful statement instead of an irritant. Motor rhythms and changing meters take on an unbridled gaiety (in spite of the technical difficulties they present to the pianists). It is this emotional connection with and need to communicate the essence of the American psyche that makes Persichetti sound so American.

In his aptly named Concerto for Two Solo Pianos, David Diamond exploits the percussive edge of the piano. Precision of attack is not used for clarity alone, but also to convey the brute power of the instruments, whose “bite” is always felt, even in the most densely scored passages. We are not hearing two pianos as an orchestra but rather the sheer power of the instruments themselves. Diamond forces his pianists to be athletes. This is in itself a very American concept: Our conservatories train for strength; the American-built Steinway is constructed with a much heavier action than its European counterpart. As sonically overwhelming as the Concerto often becomes, Diamond never fails to make an emotional connection.

Preview Excerpts

VINCENT PERSICHETTI (1915–1987)

Sonata for Two Pianos, Op. 13

SAMUEL BARBER (1910–1981)

Souvenirs, Op. 28 (original version for piano four-hands)

VINCENT PERSICHETTI

DAVID DIAMOND (1915-2005)

Concerto for Two Solo Pianos

JOSEPH FENNIMORE (b. 1940)

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletAmerican Works for Piano Duo

Notes by Steven Ledbetter

Vincent Persichetti (1915–1987)

Sonata for Two Pianos, Opus 13 (1940)

Vincent Persichetti was truly a Philadelphia composer: born in the city and a resident virtually all his life. For many years he was also on the faculty of the Juilliard School and chairman of its composition department. He had an unrivaled technique, and produced more than 160 works, including nine symphonies (No. 6, for band rather than orchestra, is a cornerstone of that repertory), other orchestral compositions, a number of choral and vocal works, and a large body of chamber works and pieces for solo piano. He described his music as falling into two categories, the “graceful” and the “gritty.” Persichetti believed a composer should take advantage of all the possibilities offered by contemporary music and integrate them fluently into his work. Accordingly, his own music covered a wide range of stylistic and expressive approaches.

Persichetti’s large output for the piano is particularly noteworthy. He composed the Sonata for Two Pianos in 1940, between his second and third solo sonatas. The two-piano sonata is rhythmically precise and contrapuntally active. Long, leaping lines in one part contrast with tiny motivic figures in the other. The crisply dotted motion of the opening Lento suggests a French Baroque overture, especially when new material in a faster tempo enters, although little else about the piece seems Baroque. Overall, the movement appears to be an extended processional.

The second movement begins as a graceful waltz. It eventually becomes unsettled and assertive, ultimately building to a large climax that quickly dissipates. The Largo is filled with lines that soar above and resolve in hushed tones. The finale is a vigorous asymmetrical dance filled with high energy.

Concerto for Piano Four-Hands Opus 56 (1952)

Persichetti’s Concerto is cast in the arch of a single movement with a long-range plan that takes us through four tempo changes and a coda. The opening Lento conjures a dark, fearsome place gradually brought to life by a high tolling chime. The next section, marked Andante, begins with a gently rolling gesture that becomes more and more insistent, to the point of defiance. The ensuing Presto is a wild frenzy of unison writing for four- hands. This fully developed, highly athletic section requires great physical stamina as the pianists must play at breakneck speeds and at the same time convey the jazzy, biting rhythms and numerous changes of meter. The following Larghissimo reflects back to the opening melody, which now appears particularly haunting. The Coda makes use of the Presto’s opening theme, but as processed through an organ grinder: first at a tempo too slow, then accelerating until wildly out of control. The piece culminates with chordal gestures that are an accumulation of harmonies heard throughout the work.

Samuel Barber (1910–1981)

Souvenirs, Opus 28 (1952)

Samuel Barber was the nephew of the great contralto Louise Homer, and he himself studied singing at the Curtis Institute with baritone Emilio de Gogorza. In the Renaissance, most composers practiced the vocal arts, but few since have attained competence as singers. Barber is among the few who have. Barber also majored in piano and composition and was by all accounts a “triple threat,” excelling equally in all three areas of his scholarship. As a composer, Barber found success early in the support of Arturo Toscanini, who played two of Barber’s works — Essay for Orchestra No. 1 and Adagio for Strings — on his November 5, 1938 NBC Symphony radio broadcast, making the young composer famous overnight.

Barber’s approach was essentially romantic, a style that served him well for symphonies and other orchestral works, choruses and songs, and two operas. He could be playful as well, as with his delightful Souvenirs. Barber explained,

In 1952 I was writing some duets for one piano to play with a friend, and Lincoln Kirstein suggested I orchestrate them for a ballet. Commissioned by Ballet Society, the suite consists of a waltz, a schottische, pas de deux, twostep, hesitation tango, and galop. One might imagine a divertissement in a setting of the Palm Court of the Hotel Plaza in New York, the year about 1914, epoch of the first tangoes.

Souvenirs pokes good-natured fun at the conventions of the various dances. In this case, the piano duets were Barber’s original conception for these cheeky pieces, while the orchestral score came as an afterthought. More than just clever, the dances feature piano writing that is highly virtuostic. The quickness of its attacks and its uncompromising rhythmic precision makes Souvenirs a tour de force of the piano duet literature.

David Diamond (b. 1915)

Concerto for Two Solo Pianos (1942)

David Diamond was born in Rochester, N.Y. He studied at the Cleveland Institute, the Eastman School (with Bernard Rogers), the Dalcroze Institute in New York (with Paul Boepple and Roger Sessions), and went to France for lessons with Nadia Boulanger. Around the early 1940s, his works began to be frequently performed, in particular Rounds, for string orchestra, which won the New York Music Critics Circle Award in 1944. Diamond lived in Italy from 1951 until his 50th birthday, when he returned to the United States and assumed a number of teaching positions, including a chair in composition at Juilliard starting in 1973. His output is large and varied, including eleven symphonies and many other works for full or chamber orchestra, operas, the ballets TOM (scenario by E.E. Cummings) and The Dream of Audibon (Glenway Wescott), incidental music for theater pieces, many songs, and chamber works.

The 1942 Concerto is a wonderfully vigorous and lively work. The initial Allegro is aggressive, finding its power and energy in march rhythms, broad leaps, and dense textures. The Adagio is gently lyrical, with an opening phrase that has a passing touch of Claire de lune. It grows to a powerful climax before sinking quietly back to its opening mood. The finale begins with roars from both pianos but then turns into a lively Allegro vivace dance movement that tosses themes back and forth in high spirits.

Joseph Fennimore (b. 1940)

Crystal Stairs (1981)

A pianist as well as a composer, Joseph Fennimore lives in upstate New York. He wrote the four-hand version of Crystal Stairs in 1981 for Joann Rautenberg and Hazel Bundy. The single movement work is inspired by Langston Hughes’s poem, Mother to Son:

Well, son, I’ll tell you: Life for me ain’t been no crystal stair. It’s had tacks in it, And splinters, And boards torn up, And places with no carpet on the floor — Bare. But all the time I’se been a-climbin’ on, And reachin’ landin’s, And turnin’ corners, And sometimes goin’ in the dark Where there ain’t been no light. So, boy, don’t you turn back. Don’t you set down on the steps. ’Cause you finds it’s kinder hard. Don’t you fall now — For I’se still goin’, honey, I’se still climbin’, And life for me ain’t been no crystal stair.

The score is filled with the syncopations of ragtime (which are here used for larger structural ends) and apparent recollections of spirituals. The composer offers the following commentary:

I grew up in bars and at the movies. That plus a year, at age 16, of playing Jerry Lee Lewis piano in a rock-and-roll band provided a powerful inoculation against the prevalent snobbery toward pop music I encountered at conservatory. My job as substitute assistant conductor for the Broadway Prodution of No, No Nanette in the 1970s served as a booster shot. Since then, my lapses into the vocabulary and practices of movie and pop music from the first half of the 20th Century have been regular and fairly frequent. Crystal Stairs is upstairs glitz. Downstairs hides Langston Hughes’s poor mom, slaving away for loved ones while yearning to be a starlet in one of Busby Berkeley’s extravaganzas. She’s a heroine, but no cameras are running. She might not know that if you get close enough to show biz, you see that, despite its glories, it’s dirtier in its way than the filthiest staircase in need of a good scrub. Clean is only in dreams, but dreams remain something movies and music do best.

Crystal Stairs shares the keyboard style and variation techniques of Liszt’s Piano Concerti. But while Liszt was trying to fashion “music of the future,” Crystal Stairs is tailored to suggest a garment from the past; it is costume music. It also exists in versions for solo piano and two pianos, and for piano and orchestra as my 2nd Piano Concerto. Four tubas is next.

Album Details

Total Time: 74:45

Recorded: Mandel Hall at the University of Chicago June 14, 15, 17 & 18, 2002

Producer: Elizabeth Ostrow

Engineers: Bill Maylone

Front Cover Photograph: Nesha & Kumiko Fotodesign

Graphic Design: Melanie Germond

Notes: Stephen Ledbetter

©2003 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 069