Store

Fantaisie combines CD rarities, such as Phillippe Gaubert’s Fantaisie and Albert Franz Doppler’s Fantaisie Pastorale Hongroise, with works that constitute essential listening for flute enthusiasts, including Gabriel Fauré’s Fantaisie, Op. 79, and Francois Borne’s Fantaisie Brillante on Themes from Bizet’s Carmen. There are virtuosic pieces written for the annual, competitive Concours examination at the Paris Conservatory — the fantasies by Fauré, Gaubert, and Georges Hüe — and works that elaborate on opera themes and folk tunes: the fantasies by Doppler and Borne plus Paul Taffanel’s Fantaisie on Themes From Weber’s Der Freischütz, one of the great opera fantasies for any instrument.

Preview Excerpts

GABRIEL FAURÉ (1845–1924)

PHILLIPPE GAUBERT (1879–1941)

GEORGES HÜE (1858–1948)

ALBERT FRANZ DOPPLER (1821–1883)

PAUL TAFFANEL (1844–1908)

FRANÇOIS BORNE (1840–1920)

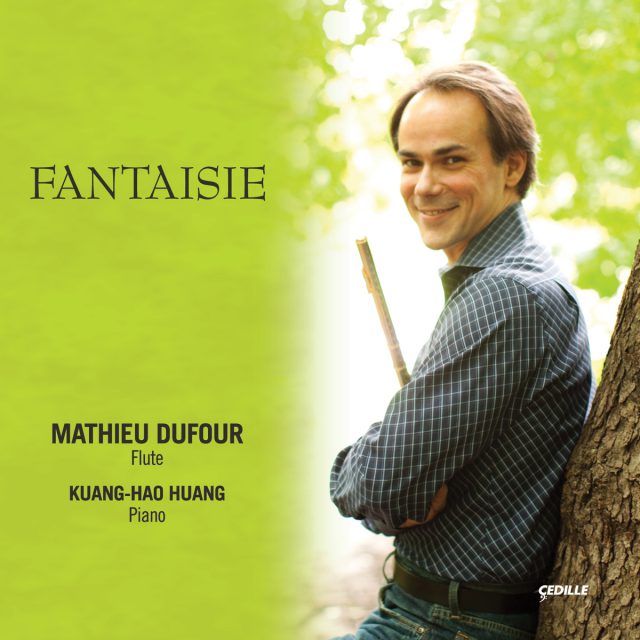

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletFantaisie

Notes by Andrea Lamoreaux

…A song by turns languorous or merry

That my dear love plays.

And when I go to the window

It seems to me that each note flies

From the flute to my cheek

Like a mysterious kiss.

Like a mysterious kiss.

—Arthur Leclere (aka Tristan Klingsor) from

“La Flute enchantee” in his poetry collection Shéhérazade

Fantasia: An ingenious and imaginative instrumental composition, often characterized by distortion, exaggeration, and elusiveness. . . . “Fantasia” has often been used [to describe] pieces that attempt to capture the character [of] improvisation, as well as for didactic compositions by players wishing to illustrate the art.

—Harvard Dictionary of Music

During the Renaissance, when the term first came into currency, fantasias were almost always keyboard works. In the 17th century, Purcell’s instrumental catalogue contained a remarkable series of fantasias for viol consort. Bach and Mozart brought the tradition of the keyboard fantasia into the late-Baroque and Classical eras with their fantasias for organ, harpsichord, or fortepiano. Precise formal structure — usually very important to both Bach and Mozart — is not a feature of fantasia composition. While all music has structure, fantasias have a tendency to create their own formal designs, which may have been part of their appeal for Romantic composers, whose yearning for expressive beauty of melody and sonority often overpowered the requirements of traditional forms. Fantasias abound in 19th-century musical literature. “For the Romantics,” writes critic and historian William Drabkin, “the fantasia went beyond the idea of a keyboard piece arising essentially from improvised or improvisatory material though still having a definite formal design. To them the fantasia . . . provided the means for an expansion of forms, both thematically and emotionally. The sonata itself had crystallized into a more or less rigid formal scheme, and the fantasia offered far greater freedom in the use of thematic material and virtuoso writing.”

The fantasias on this CD are of two different types. Three of them — those by Doppler, Borne, and Taffanel — are in the traditions of Liszt, who wrote a number of piano works elaborating themes from operas, and Max Bruch, whose Scottish Fantasy incorporates traditional folk tunes. The works by Fauré, Gaubert, and Hüe stem from the stellar tradition of flute virtuosity centered at the Paris Conservatory in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Founded in 1793, the Conservatoire has long been a mecca for aspiring flute soloists. The annual competitive examination called the Concours began in the 1890s and was supervised for more than a decade by Paul Taffanel (1844–1908). He is regarded as the founder of the modern school of French flute playing; his traditions were carried on by Philippe Gaubert and Marcel Moyse, among others. Fantasias composed for the Concours were designed to show off the student’s ability to play in a lyrical, expressive style, and also challenge his (or her) technical accomplishments with opportunities for fast fingering and articulation.

A prolific song composer, Gabriel Fauré (1845–1924) also wrote orchestral, solo piano, and chamber music. Originally trained on the organ, Fauré earned his living as an organist until he began to gain recognition as a composer. In 1896, he joined the faculty of the Paris Conservatory and became its director in 1905. His students included composers Maurice Ravel and Georges Enescu, and the noted composer-teacher Nadia Boulanger. He wrote his Fantaisie for the flute Concours of 1898 and dedicated it to Taffanel; it also exists in an orchestral version. The opening section, marked Andantino (moderately slow), is in E minor and proceeds in 6/8 time. It is reminiscent of a Siciliana (a favorite slow-movement style of Baroque composers), with a pastoral mood and occasional dotted-rhythm figures. (Fauré was working on the famous Sicilienne movement of his music for the play Pelléas et Mélisande at the same time.) The melody of the Fantaisie’s opening section becomes increasingly elaborate, ending with an E minor cadence, a short rest, and a quick shift into 2/4 time and an Allegro main section in C major. The flute and piano parts both become increasingly complex and intense, passing briefly through many keys, alternating between staccato and legato playing. The sudden dynamic contrasts enhance the sense of building to a heady climax.

One of Taffanel’s most famous students was Philippe Gaubert (1879–1941), who had a three-way career as composer, conductor, and teacher. He became artistic director of the Paris Opera in 1931 but never lost his connection to flute music, working with Taffanel on a flute teaching manual and holding a professorship at the Conservatory. Although he composed for orchestra, ballet, and solo voice, he is remembered mainly for his compositions featuring the flute. He wrote his Fantaisie for the Conservatory’s 1920 Concours. Its two principal sections are labeled Moderato Quasi Fantasia and Vif (lively), but there are many tempo variations within each portion — subtle indications asking the players to speed up or slow down. The opening section is similar to a concerto cadenza, with virtuosic, improvisatory passages for both instruments. The key is (mostly) G minor. A Lent (slow) passage ushers an elaborate theme for the flute before the start of the Vif section in B-flat, the relative-major. The initial melodies cover the range of a major seventh. They sound very much like incomplete scales and lend a sense of indeterminacy. There are abrupt dynamic changes as the piano plays trills and rapid chord patterns to support the flutist’s exploration of his entire range. New motives emerge, often echoing, elaborating, and re-turning to the basic major-seventh pattern. Several keys are briefly explored, with a return to G minor near the end and a final piano chord in G major.

Like Fauré, Georges Hüe (1858–1948) was mainly noted for vocal music — songs and operas — and was not a flute player. He divided his career between composing and teaching throughout his long life. His works recall the harmonic world of Debussy. He wrote his Fantaisie for the Concours of 1913 (he orchestrated it ten years later). Like Gaubert’s piece, it begins with a cadenza-like section. The opening key is G minor, rhythmic patterns are dotted and almost hesitant, the flute has a long, brilliant passage over sustained piano chords. A sudden modulation to A major brings in much calmer lyrical thematic material marked Modéré, in relaxed 12/8 time, with a soft dynamic marking. The melodies are increasingly elaborated until we return to Tempo I — Assez Lent (rather slow) — and the original improvisatory motives. An echo of the A major theme leads to a fast section introduced by staccato notes in the piano part, a very different and more agitated sound for both instruments. The rhythm changes to a rapid waltz. Sudden changes of key, dynamics, and major-minor modality increase the emotional intensity. New melodies are introduced and interrupted by bravura measures of virtuosic display. After touching on a number of keys, the piece ends with a triumphant coda in B-flat major.

We move back a generation or two, and eastward from France, for the famous Hungarian Pastoral Fantasy by Albert Franz Doppler (1821–1883). Much of Doppler’s writing was inspired by traditional music of central Europe; his family had connections in Poland and Hungary and won fame as composers, conductors, pianists, and flutists. Doppler wrote operas for theaters in Budapest and had a notable career in Vienna as both a composer and flute virtuoso. Whether his Fantaisie uses authentic Hungarian folk melodies (as researched by Bartók and Kodály much later in the 19th century) is impossible to determine, but he creates a compelling piece from simple tunes, wherever they may have originated. The melancholy opening section, Molto Andante in D minor, is virtuosic for the flute and dramatic for the piano. A quick shift to D major brings a new theme and faster pace; the theme is varied and constantly elaborated, with miniature cadenzas in both instrumental parts. An Allegro section returns to D minor and drops into a mysterious pianissimo passage; then we come back to the major mode to lead into a flute cadenza accompanied by soft piano chords and a brilliant fortissimo D major coda.

Taffanel taught a generation of flute players and wrote a great deal of music for his beloved instrument over the course of a distinguished career that also encompassed solo and chamber music performances and conducting. His ingenious Fantaisie on Themes from Der Freischutz could serve as an alternative overture to that opera (not that anyone will ever become tired of Carl Maria von Weber’s original overture, a concert favorite). Not so well known in the United States, Der Freischutz was a milestone in the evolution of German opera when it premiered in Berlin in 1821. Based on legends of the Dark Huntsman, it is both a love story and a Faustian tale of men imperiling their souls by dealing with the devil. Weber’s genius for colorful orchestration and memorable melodies made the opera a hit, and it had a tremendous influence on the young Richard Wagner. Taffanel’s reinterpretation of its themes recognizes the importance of the orchestra in Weber’s work by placing special emphasis on the piano part; the keyboard player here is far more than an accompanist. The agitated introduction hints at the dark images of the opera’s Wolf Glen scene, where the hunters Max and Caspar invoke the Dark Huntsman to help them forge magic bullets that will always hit their mark — for a price, of course. The main body of the Fantaisie, however, moves away from the demonic to the prayerful. From the Allegro minor-mode introduction we move to a D major section based on one of the opera’s principal arias, “Leise, leise, fromme Weise” (Softly, gentle air, waft up to the stars). It is sung by the opera’s heroine, Agathe, in love with Max, who must win a shooting competition to gain her hand in marriage. Agathe knows Max has been tempted by the idea of the magic bullets but, in the course of the aria, reaffirms her faith in his goodness and greets his return with joy. The Fantaisie follows this progression with a brilliant Allegro variation on the concluding part of her aria, which signals his return to her. In Act III, Agathe contemplates the competition with renewed foreboding and sends up a prayer, “Und ob die Wolke” (And even if clouds veil it, the sun still shines in heaven). The flute presents this yearning, lyrical melody in a passage marked Andante Quasi Allegretto, a very moderate and serene tempo. The piano at first supports the aria theme, then takes it over as the flute plays imaginative figurations. The final Allegro energico reverts to a lighter aspect of the plot: Agathe’s friendship with Ännchen, who tries to allay her fears in the playful aria, “Kommt ein schlanker Bursch gegangen” (Whenever an attractive boy walks by). Taffanel turns this theme into a propulsive finale for both players.

François Borne (1840–1920) is credited with improvements in flute-building while he taught at the Conservatory of Toulouse and played principal flute in the theater orchestra of Bordeaux. He is remembered by flutists and non-flutists alike for his Fantaisie Brillante sur Carmen, reproducing and varying themes from the most famous of all French operas. An agitated piano introduction leads to a flute melody drawn from one of the opera’s entr’acte portions. Then, in an ominous C minor, we hear the “fate” theme from the Act I Prelude, with tremolos in the piano part supporting the portentous melody. Figurations and variants build up until we hear a brief reference to the chorus in Act I where soldiers and townspeople greet the appearance of Carmen; then the flute sings the theme of her “Habanera.” The piano part imitates the original orchestral scoring with haunting effect. Two variations on the “Habanera” follow, the flute elaborating while the piano maintains the tune. The piano plays the throbbing theme of the “Gypsy Dance” that opens Act II. The flute picks it up, and both instruments cascade through brilliant elaborations. Suddenly, we shift from minor to major mode for a triumphant presentation of the “Toreador Song” that builds up to a dizzying finale.

Andrea Lamoreaux is music director of 98.7 WFMT, Chicago’s classical experience.

Album Details

Total Time: 57:00

Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineer: Bill Maylone

Editing: Jeanne Velonis

Technical Editing: Bill Maylone

Recorded May 31 – June 2, 2009, in Ganz Hall, Chicago College of Performing Arts at Roosevelt University

Steinway Piano, Piano Technician: Nobumaso Fujiwara

© 2010 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 121