Store

Store

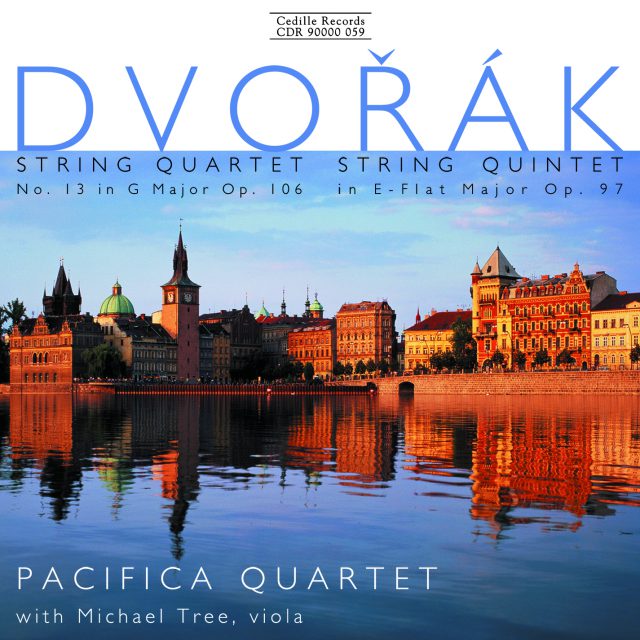

Dvorak: Quartet Op. 106 and Quintet Op. 97

Chamber music occupied a special place in Dvorak’s heart. This CD of two of his finest — and less well-known — chamber works will earn a cherished spot in your record collection.

Dvorak composed his richly textured String Quintet in E-flat Major, Op. 97 (1893) during a sojourn in Iowa. It radiates Dvorak’s warmth and humanity while also echoing his encounters with the music of different Native American tribes.

Poetic and expressive, the landmark String Quartet No. 13 in G Major, Op. 106 (1895) shows Dvorak in his creative prime. “What marvelous music,” says Gramophone magazine. “Why is it so rarely heard? . . . Why don’t some of our younger quartets tackle this masterpiece?”

At last, one of them has. On this new Cedille recording, the Naumburg Award-winning Pacifica Quartet, a bold and dynamic young ensemble (“They all move on the same strong, supple band of time.” — New York Times), rises to the challenge, joined in the quintet by violist Michael Tree of the Guarneri Quartet.

Preview Excerpts

ANTONIN DVORAK (1841 - 1904)

String Quartet No. 13 in G Major, Op. 106

String Quintet in E-flat Major, Op. 97

Artists

5: with Michael Tree, viola

Program Notes

Download Album BookletDvorak Quartet in G major, Op. 106 and Quintet in E-flat major, Op. 97

Notes by Wayne Booth and Yonatan Malin

Antonín Dvorák’s life (1841-1904) was in many ways strikingly different from those of the contemporaneous composers who influenced him, such as Wagner, Smetana, and especially Brahms. (Earlier influences included, as one would expect, Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, and Liszt). None of these Dvorák contemporaries came from “peasant” families. Antonín’s father was a butcher who tried hard to pass the business on to his son, even while ensuring his training as a “fiddler” and singer. Most of his composing peers received a far more intensive childhood musical and cultural education—and they usually attained favorable responses to their early compositions.

Dvorák’s earliest efforts were rejected by almost everyone; he made his living early on as a violist, organist, and music teacher. Lacking external confirmation of his own abilities, Dvorák nonetheless composed morning, noon, and night. He was always extremely critical of his work and, like Brahms—who later became not only a mentor but also a close friend— Dvorák deliberately tore up many of his earliest “completed” works. Those he preserved were all intensely revised as he matured.

Only in his early thirties did signs of success begin to emerge. In his forties he experienced an astonishing rise to international acclaim. At the age of fifty, in 1891, his European fame led to an invitation from the National Conservatory of Music in New York City to become its Director and conduct six concerts of his work, while also teaching composition. Though reluctant to leave his beloved homeland, he came for two visits, first from September 1892 to March 1894 and then, even more reluctantly, October 1894 to April 1895.

To his surprise, he fell in love with much of American popular music. Everyone agrees that his encounter with American culture was immensely influential on his later work. That influence is most evident in his Symphony No. 9 in F minor, Op. 95, “From the New World”, and the “American” Quartet in F major, Op. 96. It is also noticeable in the two works recorded here—especially in the opus 97 Quintet. Dvorák did not compose the opus 106 Quartet until he returned home, but he conceived some of its substance while still in America.

Critics generally agree that these two compositions are among his finest. They both embody his intense, lifetime love of chamber music, his mature mastery of classical form intricacies, and his revolutionary commitment to folk melody, achieving passionate emotional tensions. They celebrate the joy of life while also exhibiting the profound grief that the loss of his children and many of his friends had produced.

Along with his assigned concert and teaching duties in New York City, Dvorák managed to compose several works including the “New World” Symphony, the “American” Quartet, and the somewhat routine commemorative work, The American Flag, written for the 1892 Columbus Centennial.

From the beginning he experienced an increasing love for American folk music, especially African American and Native American. Yet he also longed for Czech culture. Unable to get home, he managed to arrange a “vacation” with his family in a tiny Midwestern village of Czech settlers: Spillville, Iowa. Dvorák found it a curious place:

It is very strange here. Few people and a great deal of empty space. A farmer’s nearest neighbor is often 4 miles off, especially in the prairies (I call them the Sahara) [where] there are only endless acres of field and meadow and that is all you see. You don’t meet a soul (here they only ride on horseback) and you are glad to see in the woods and meadows the huge herds of cattle which, summer and winter, are out at pasture in the broad fields. Men go to the woods and meadows where the cows graze to milk them. And so it is very “wild” here and sometimes very sad, sad to despair. (John C. Tibbett, Dvorák in America)

Surrounded in Spillville both by friends of Czech origin and by African-Americans and Native Americans playing and singing music, Dvorák quickly began compositions influenced by that music. First came the famous “American” Quartet, beautifully loaded with the pentatonic scales that infused so much of the music he was hearing. Then, after listening to more music performed by visitors to the town said to be of the Kickapoo tribe, he composed the opus 97 Quintet. Written in five weeks in 1893, this marvelous work had immediate success and increased speculation about Dvorák’s American influences.

The key melodies, such as those central in movements one and three, have invited critics to debate whether Dvorák got them from American or Slovak folk music. How can one decide, since pentatonics are fundamental to both musical cultures? Are critics right to say that he got the bouncing rhythm of the second movement scherzo from Native American drum rhythms?

The Quintet opens with a pentatonic melody for solo viola (Dvorák’s own instrument). This melody returns first in the minor mode, then in the major, with faster rhythms as the movement gets under way in earnest, building to its first climax. For the second theme of the first movement Dvorák adapted a Native American melody that he heard in Spillville. Its light, dotted rhythms, echoing Algonquin drumming patterns, return throughout this movement as well as in the Finale. The two violas trade a melancholy theme in the development, and Dvorák weaves a recollection of the viola’s opening melody into the movement’s peaceful ending.

The second movement, a scherzo and trio, begins, like the first, with a viola solo; but here it is a tricky rhythm played on a single note, an ostinato that continues to sound as melodic layers are added. A long arching melody with unexpected harmonic turns passes from viola to violin in the trio section. Many consider the slow third movement the emotional heart of the Quintet; it is a set of variations on two themes, the first minor and the second major. Dvorák originally wrote the second theme as a prospective American anthem: a musical setting for “My Country, ’Tis of Thee.”

The Finale is a surprisingly light-hearted rondo with contrasting episodes and a dervish-like finish. Some critics have declared it a disappointingly frivolous anti-climax to one of Dvorák’s (otherwise) greatest achievements. Less erudite listeners, however, will find themselves too busy singing its catchy melodies (which half-reflect the earlier movements) to take any charges of banality seriously.

Despite its wonders, the Quintet is not performed nearly as often as its immediate predecessor, the “American” Quartet. It is, nonetheless, an amazing achievement, avoiding the clichés of some of his lesser work, with just the right amount of formal sophistication: enough to enhance the appeal of its melodic and harmonic material without calling attention to the work’s construction.

Some have interpreted the opus 106 Quartet, not written until his return home, as expressing Dvorak’s joy over escaping from America, “a fervent thanksgiving for homecoming” (in the words of one critic). That is certainly possible, since the American influences are much harder to detect. Some who consider it his greatest quartet even claim that in it he ruled out American influences entirely. But anyone who listens closely will hear that American melodies and rhythms were still in his soul.

The Quartet opens with a series of contrasting motives — rising leaps, trills, and descending arpeggios— said by some to echo birdsongs he had heard in Spillville. These are then developed with amazing energy. Only after the treatment of the opening figures subsides does he introduce the central melody, first in fragments, then fully exuberant, and finally dissolving as dissonant harmonies (marked feroce) take over. Improvisatory gestures with sudden changes of pacing lead into a lyrical second theme. The development section draws the opening motives and first theme into a Beethoven-like drama; there is even a moment of jagged fury in the recapitulation that recalls Beethoven’s Grosse Fuge. Dvorák’s lyricism, however, returns again and again, holding its own against the impassioned outbursts.

Early Dvorák biographer Otakar Sourek described the second movement as “one of the loveliest and most profound slow movements in Dvorák’s creation.” Like the slow movement of the Quintet, it is a set of variations on a pair of themes, but here each variation grows and develops, reaching beyond the bounds of its theme. The first theme, in E-flat minor, is full of pathos, while the second, in E-flat major, is tender and peaceful. In the middle of the movement, the first theme is developed with greater and greater ferocity until a grand statement of the second theme breaks through. At this moment the quartet truly sounds like an orchestra, with each instrument playing full-voiced chords. Rarely does any composer produce a theme-and-variations movement as profoundly moving and interesting as this one.

The third movement is a scherzo with a main theme that sounds rather rough, especially after the slow movement’s tender ending. Dvorák pushes against the boundaries of decorum as dissonances pile up over static harmonies and repeating rhythms. There are two trio sections. The first trio’s pastoral mode is pure Dvorák, with a pentatonic melody that is serene, sweet, and touched with nostalgia. Juxtapositions of duple and triple rhythms create shimmering textures. In the second trio, Dvorák demonstrates his mastery of the classical idiom; it would sound perfectly at home in many of Beethoven’s quartets.

The Finale is a rondo with a slow, hymn-like introduction and a movingly syncopated main subject. Its frequent and aggressive assertions of affirmation seem to say, “No more of that sad sentiment. It’s all . . .OK!” A return of the hymn-like introduction in the middle of the movement leads to tender recollections of the first movement. These recollections are again and again placed in dialogue with darker material and with the chanted affirmations. Each idea attempts to seize control of the music, but all give way to the main subject, and the quartet ends with triumphant exuberance.

These two works are without doubt not just among the best of Dvorák’s chamber music, but also among the greatest in the entire western tradition. Like all of his finest works, they combine romantic lyricism with a classical sense of form and the emotional simplicity of folk music. Those who listen closely can easily imagine themselves glimpsing landscapes that enthrall and shimmer, as individual themes emerge from and transform the musical flow.

Wayne Booth is Professor of English Emeritus at the University of Chicago. Yonatan Malin is a graduate student in the Department of Music at the University of Chicago.

Album Details

Total Time: 75:40

Recorded: February and April 2001 at WFMT, Chicago

Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineer: Bill Maylone

Cover Photography: Prague, Czech Republic © Joe Cornish/Stone

Design: Melanie Germond

Notes: Wayne Booth

© 2001 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 059