Store

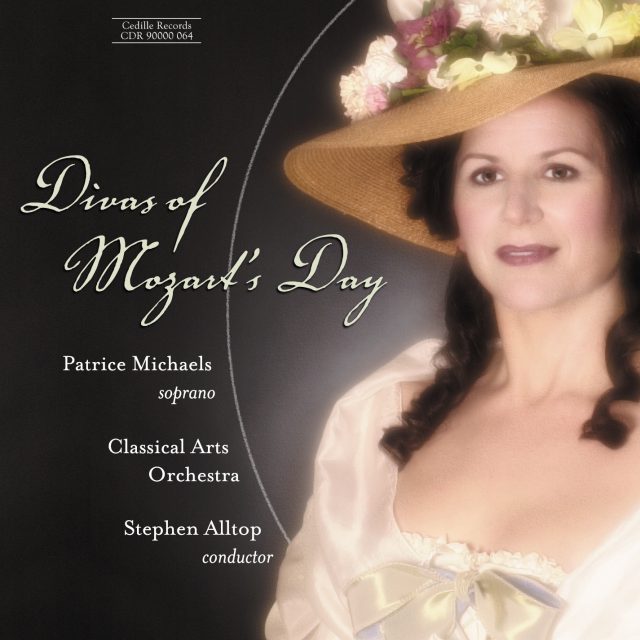

Acclaimed soprano Patrice Michaels evokes the leading prima donnas of classical-period Vienna by singing pieces tailored to their talents by Mozart and fellow composers Salieri, Martin y Soler, Cimarosa, Righini, and Stephen Storace.

Hear works written for Nancy Storace (the original Susanna in The Marriage of Figaro), Caterina Cavalieri (the first Constanze in The Abduction from the Seraglio), Luisa Laschi Mombelli (the first Countess), Adriana Ferrarese (the first Fiordiligi), and Louise Villeneuve (the first Dorabella).

Portraits of these singers emerge through the radiant voice of Patrice Michaels and the period-instrument prowess of the Classical Arts Orchestra, conducted by Stephen Alltop. The program includes two never-before recorded Mozart recitatives and a rarely heard duet Mozart wrote for the 1788 Vienna production of Don Giovanni.

Preview Excerpts

WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART (1756-1791)

VINCENZO RIGHINI (1756-1812)

ANTONIO SALIERI (1750-1825)

WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART

VICENTE MARTÍN Y SOLER (1754-1806)

ANTONIO SALIERI

STEPHEN STORACE (1762-1796)

WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART

ANTONIO SALIERI

WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART

VICENTE MARTÍN Y SOLER

WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART

Substitute aria in Martin y Solers Il burbero di buon core (1789)

WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART

Insertion aria in Guglielmi’s La quakera spiritosa (1790)

Artists

4: with Stephen Alltop, fortepiano solo

6: with Peter Van De Graaff, bass-baritone

10: with Peter Van De GraaV, bass-baritone

Program Notes

Download Album BookletThe Divas of Mozart’s Day

Notes by Dorothea Link

When Mozart settled in Vienna in 1781, he was almost immediately commissioned to write an opera for the Singspiel Company that formed part of the Imperial and Royal National Court Theater founded and administered by Emperor Joseph II. This company, like the genre itself (German opera employing spoken dialogue instead of sung recitative), could not yet boast any great artistic successes, but Joseph nurtured it along, partly to support local talent and partly to avoid having to spend large amounts on imported opera. Encouraged by the success of his self-supporting theater, he created an opera buffa company in 1783 for which he engaged expensive singers from Italy. The Singspiel was then dissolved, and many of its singers were absorbed into the Italian company. In 1785, however, the Singspiel was revived for a further two and a half years, during which it coexisted with the buffa company. In the space of a few years, there came a succession of great operas by composers such as Mozart, court composer and Kapellmeister of the opera buffa Antonio Salieri, and visiting composer Vicente Martín y Soler. Lorenzo Da Ponte, the company’s librettist, furnished most of the texts. Due to constraints imposed by the onset of war with Turkey in 1788, the Singspiel was again dissolved and the Italian opera was pared down. Artistic momentum continued nonetheless, producing further masterpieces from Salieri and Mozart. This great era for opera at the imperial court came to an end with the death of Emperor Joseph in 1790 (and, of course, Mozart in 1791).

Each of the five prime donne featured on this recording contributed to the brilliance of Joseph’s opera. Catarina Cavalieri was present from the very beginning. Throughout her long tenure at the court opera, she sang in both Singspiel and opera buffa. In Singspiel she usually took the leading roles; in opera buffa, however, she was often consigned to secondary parts. Nancy Storace was the opera buffa company’s first prima donna. She initially sang prima donna seria parts, but eventually switched to prima donna buffa roles. Often partnered with Storace was Luisa Laschi Mombelli: when Storace sang the serious female part, Laschi took the comic role (and later vice versa). Laschi was an extraordinarily versatile singer, who apparently could excel in a wide range of parts. She was therefore not threatened by the arrival of Adriana Ferrarese del Bene midway through the 1788-89 season. Ferrarese was exclusively a seria singer, not quite exceptional enough for opera seria on the international stage in London, but greatly valued for her vocal prowess in smaller houses and in opera buffa, in which she took the serious roles. Laschi was replaced the following season by Louise Villeneuve who, like Laschi, could sing comic and serious roles equally well.

These glorious voices may seem to have vanished forever, but they are not entirely lost. Because composers of that era fashioned their music to the voices of the singers who were to perform it, arias composed for a particular singer capture and preserve the characteristics of her voice. By identifying and colleting such arias, it is possible to some extent to recover the special qualities of their voices. This recording presents a selection of arias by Mozart and his Viennese contemporaries, chosen to create a vocal profile for each of the five divas. Except for the Mozart selections, the pieces are largely unknown today (and even in Mozart’s case, the works are not commonplace — including two previously unrecorded accompanied recitatives). For all of these (non-Mozart pieces) but one, the scores were drawn from original manuscript sources in the Austrian National Library; Stephen Storace’s own published score was used for the English aria on track 7.

CATERINA CAVALIERI (1755 – 1801)

A native of Vienna, she spent her entire career in the service of the imperial court theater. She ranked highest among the German female singers, but took second place to the Italians. Emperor Joseph II valued Cavalieri for her willingness to sing whatever roles she was assigned, whether in German or Italian opera, even while he acknowledged her lack of versatility. She could deliver a tortuously demanding bravura aria with every note in place, but expressing tender sentiments that required nuanced acting was apparently difficult for her. Cavalieri was a pupil of court composer Antonio Salieri, and was rumored to have been his mistress.

Mozart wrote a great deal of memorable music for Cavalieri, beginning with Constanze in Die Entführung aus dem Serail in 1782. He was quick to exploit her strengths, as he reported to his father in his letter of September 26, 1781: “I sacrificed Konstanze’s aria a bit to the agile throat of Mlle Cavalieri.” That was only the first aria “Ach, ich liebte.” The virtuosic writing culminated in the second-at show-stopper “Martern aller Arten.” Four years later, as Mlle Silberklang in Der Schauspieldirektor, Cavalieri portrayed a coloratura soprano who could contentedly sing an entire aria on the word “allegro.” When she was cast as Elvira in the 1788 Viennese production of Don Giovanni, Mozart wrote “Mi tradì” for her, using fioratura as a means of depicting Elvira’s internal struggle. For the 1789 Viennese revival of Le nozze di Figaro, in which she sang the Countess, Mozart revised “Dove sono” to include several passages of fioratura. This did not just serve to show of Cavalieri’s voice: in accord with late 18th century convention, it also strengthened the characterization of the Countess as a person of nobility. Perhaps this edition of the aria should be sung today; the first version is vocally plainer only because the original Countess (Laschi) did not sing fioratura.

Mozart, “Tra l’oscure ombre funeste” for soprano primo in Davidde penitente, K. 469, 1785 Mozart contributed this oratorio to the Easter fundraising concerts of the Tonkünstler-Sozietät, a pension fund for musicians’ widows and orphans. He assembled the oratorio from sections of his Mass in C minor, K. 427 (417a), Writing to it a new text (attributed to Lorenzo Da Ponte) and adding two new arias, including this one for Cavalieri. The aria opens with an Andante in C minor before moving to an Allegro in C major in which the vocal writing breaks into dazzling virtuosity, several times touching on high C. Its message expresses the joy and peace that righteous, faithful hearts may expect, even in the face of storms and threatening shadows.

Vincenzo Righini, “Per pietà, deh, ricercate” for Aurora in L’incontro inaspettato, 1785. Nunziato Porta, libretto. Righini was the most sought-after voice teacher in Vienna in the 1780s, counting among his pupils Josepha Weber Hofer, the original Königin der Nacht, and Princess Elisabeth von Württemberg, the bride of future Emperor Franz II. His Exercices pour se perfectionner dans l’art du chant were republished many times throughout Europe. Highly regarded as a composer by Vienna’s nobility, Righini wrote operas both for private commission and for the court theater. He wrote exquisitely for Cavalieri, and his beautiful orchestration for this aria features an obbligato clarinet. The opera employs a plot also used by Mozart (Die Entführung aus dem Serail), Gluck, Haydn, and others. In this aria, Aurora is distracted with grief and begs assistance in searching for her husband.

Salieri, “Wenn dem Adler das Gefieder” for Nanette in Der Rauchfangkehrer, 1781. Joseph Leopold Auenbrugger, libretto. This is Salieri’s only Singspiel, written at the request of the emperor in the fourth year of his company. Salieri used the commission as an opportunity to enter the debate over whether the German language was suitable for singing. When the leading lady declares that sung German is tasteless, her suitor replies that the problem lies not with the language but with singers who do not enunciate properly. Salieri thus expressed support for the Emperor’s Singspiel project, but also contrived to write four arias in Italian by making the opera’s protagonist an Italian singing teacher who speaks faulty German. In the opera, the wealthy young widow and former opera singer Frau von Habicht competes with her stepdaughter Nanette for marriage to a man they believe to be an Italian marchese, but who is actually a chimneysweep. In this aria, Nanette likens herself to the awe-inspiring eagle. Salieri writes a largescale coloratura piece for Cavalieri, employing features that would become characteristic of her arias: C major tonality, fiery coloratura reaching high Cs and Ds, march like dotted rhythms, and full orchestration including trumpets and timpani. Mozart used this aria as a model for his “Martern aller Arten” and also, on a smaller scale, for “Tra l’oscure ombre funeste.”

NANCY (ANNA) STORACE (1765 – 1817)

Nancy was born in London to an English mother and an Italian father, a contrabassist. When she was fourteen, her family took her to Italy where she quickly rose to the rank of prima donna. At seventeen she was engaged for the imperial court opera in Vienna. Her four years there were the most brilliant in her career. Mozart, Vicente Martín y Soler, and Salieri provided her with some of her best roles and helped dictate the course of her musical future. She arrived in Vienna with the repertoire of a prima donna seria. By the time she left, however, she had recognized that her strong acting skills, engaging stage personality, and fine musicianship made her especially gifted as a comic singer. Despite her determination to sing virtuosic arias, audiences consistently preferred her in lighter, vocally simpler pieces. In 1787storace returned to London, singing briefly in opera buffa before joining her brother, composer Stephen Storace, in English comic opera, where she enjoyed a long and celebrated career.

Mozart, “Ch’io mi scordi di te . . . Non temer, amato bene” scena con rondò, K. 505, 1787 In addition to the role of Susanna in Le nozze di Figaro, Mozart wrote two arias for Storace: “Nacqui all’aura triofale” in the unfinished opera Lo sposo deluso, 1784, and this one for her farewell recital on February 23, 1787. He conceived this concert aria on a grand scale, utilizing her virtuosity and empathetic lyricism, and creating for himself a brilliant obbligato part on the fortepiano. The text, previously used in Idomeneo, expresses undying fidelity in the face of separation and features an appeal for pity from the listeners. Following the recitative “Ch’io mi scordi di te,” the aria “Non temer, amato bene” is in the form of a rondò — a two-tempo aria that became popular in Vienna in the early 1780s. Not to be confused with the instrumental rondo form, a rondò begins with a slow section that features cantabile singing and ends with a fast section that displays the singer’s virtuosity. Reserved for the prima donna, in operas it was usually positioned immediately before the last-at finale. As Susanna in Le nozze di Figaro, Storace would have expected a rondò in the last at, and Mozart had, in fat, begun composing one: “Non tardar amato bene.” He broke of its composition, however, when he was apparently able to convince Storace to forego her showcase piece in favor of the simple but expressive aria “Deh vieni, non tardar.”

Vicente Martín y Soler, “Dolce mi parve un dì” for Lilla in Una cosa rara, 1786. Da Ponte, libretto. After spending the early part of his operatic career in Italy, the Spanish composer arrived in Vienna in late 1785. The second of three operas he composed there, Una cosa rara took the city by storm, upstaging every other opera that season, including Le nozze di Figaro. Martín’s lyrical genius was a perfect match for the pastoral subject matter, and almost every number in the opera, whether aria or ensemble, became a hit. The artful simplicity of his style suited Storace particularly well, and she created one of her most popular characters with the shepherdess Lilla. In this aria she laments her lost happiness — she and her betrothed had loved each other in perfect trust until the Prince descended upon her village and began wooing her.

Salieri, “La ra la, che fillosofo buffon” for Ofelia, with recitative for Ofelia and Trofonio in La grotta di Trofonio, 1785. Giambattista Casti, libretto The poet and political satirist Giambattista Casti appeared in Vienna in 1784, possibly to vie for the position of imperial court poet, which had been vacant since the death of Pietro Metastasio two years earlier. Casti failed to win the post, even though he wrote two highly original librettos for the court opera. The second of these — a stylized, quirky, humorously mocking libretto with an ostentatious display of erudition — La grotta di Trofonio became something of a model for Da Ponte’s Così fan tutte. Two sisters, one serious and thoughtful, the other lighthearted and spirited, are betrothed to men with matching temperaments. The local sorcerer lures the women into his cave, where he exchanges their personalities, to the bewilderment of their lovers. In this aria, the formerly serious Ofelia emerges from Trofonio’s cave, now jolly and vivacious, and makes fun of the sorcerer, much to his amusement.

Stephen Storace, “How Mistaken is the Lover” for Isabella in The Doctor and the Apothecary, 1788; originally “Care donne che bramate” for Lisetta as an insertion aria in Giovanni Paisiello’s Il re Teodoro in Venezia, 1787 Nancy’s brother composed this aria for her to sing in the London premiere of Paisiello’s opera on December 8. The piece was an immediate success, and Stephen published it on December 21. Ten days later, another publisher issued a pirated edition. Stephen launched a lawsuit and eventually won what became a landmark case in the history of copyright law in Great Britain. While waiting for the judgment, Stephen reset the music to a text by J. Cobb in this 1788 English comic opera, adapted from Ditters von Dittersdorf’s Viennese Singspiel Doktor und Apotheker. The message of this short aria is gently didactic, reminding the audience that, when it comes to love, “yes” doesn’t always mean “yes,” and “no” doesn’t always mean “no.” ADRIANA

FERRARESE DEL BENE (c.1760-after 1804)

Ferrarese brought her studies at the Venetian Conservatorio di S. Lazzaro dei Mendicanti to an end in December 1782 by eloping with Luigi del Bene. After appearing on a number of Italian stages, she accepted a two-year engagement in London beginning in 1785. At first she sang opera seria, but after the arrival of Gertrud Elizabeth Mara, Ferrarese was assigned to opera buffa, where she sang the serious roles. Upon returning to Italy, she also returned to opera seria. In Vienna, however, she was once again engaged to sing serious roles in opera buffa, making her debut there in 1788 as the goddess Diana in Martín’s L’arbore di Diana. The Rapport von Wien stated, “she has in addition to an unbelievable high register a striking low register and connoisseurs of music claim that in living memory no such voice has sounded within Vienna’s walls. One pities only that the acting of this artist did not come up to her singing.” That weakness confined Ferrarese to serious roles, leaving more interesting characters to singers such as Laschi and Villeneuve. In 1791 the new emperor reorganized the company and she was let go. She returned to Italy to sing opera seria until at least 1804. Mozart’s professional relationship with Ferrarese consisted of revising the role of Susanna for the 1789 revival of Le nozze di Figaro, and of writing Fiordiligi in Così fan tutte for her in 1790.

Mozart, “Al desio di chi t’adora,” K. 577, for Susanna in Le nozze di Figaro, 1789. Da Ponte, libretto although Ferrarese was clearly better suited to singing the Countess than Susanna, the latter role had been established as the principal female role, so Susanna she had to sing. Mozart made the best of the situation by writing two new arias. He replaced “Venite, inginocchiatevi,” which requires a great deal of acting, with “Un moto di gioja mi sento,” K. 579. He wrote to his wife on August 19, 1789, that “the little aria I have made for Ferrarese I believe will please, if she is capable of singing it in an artless manner, which I very much doubt. However, she seemed very satisfied with it.” If artlessness was not her strong suit, bravura was, and Mozart gave her plenty of opportunity to shine in the rondò “Al desio di chi t’adora,” replacing “Deh vieni, non tardar.” Vocally demanding, the aria features two basset horns, two bassoons, and two horns in a scoring that was to become characteristic of Così fan tutte, written only weeks later. Masquerading as the Countess, Susanna strikes a perfect pose as the love-lorn noblewoman, appealing directly to the audience for compassion in her misery. Count Zinzendorf noted in his diary on May 7, 1790, nine months into Figaro’s Viennese revival, “Ferrarese’s rondò always pleases.”

Salieri, “Alfin son sola…Sola e mesta fra tormenti” for Eurilla in La cifra, 1790. Da Ponte, libretto Salieri attested to Ferrarese’s talent by incorporating the following note into his autograph score: “Instrumental recitative Alfin son sola and rondò Sola e mesta fra tormenti: Pieces in the high serious style, but suitable for the person who sang them and for the situation in which she finds herself, and above all because they were composed for a famous prima donna, who could perform them most perfectly, and won the greatest applause.” Salieri scholar John Rice traces a line of influence from Mozart’s “Al desio” (composed in August 1789), through this aria (December 1789), to “Per pietà, ben mio, perdona” from Così (January 1790): all three share the rondò form, prominent horns, and vocal lines that feature Ferrarese’s celebrated leaps between head and chest voice. La cifra is the story of a beautiful and virtuous young woman who grows up as a peasant but discovers, after falling in love with a nobleman, that she is the long-lost daughter of another nobleman. In this aria, Eurilla, still ignorant of her true identity, contemplates her unhappy future.

LUISA LASCHI MOMBELLI (1763 – c.1789)

Laschi came to Vienna in 1784 for a trial period of eight months and was immediately appreciated. According to the Wiener Kronik of September 24, 1784, “she has a beautiful clear voice, which in time will become rounder and fuller; she is very musical, sings with more expression than the usual opera singers and has a beautiful figure! Madam Fischer [Nancy Storace’s married name] has only more experience, and is otherwise in no way superior to Demoiselle Laschi.” She returned to Vienna for a longer appointment in the spring of 1786 and created the Countess in Le nozze di Figaro. That season the lyric tenor Domenico Mombelli, with whom she had sung the previous year in Naples, joined the company. After learning of their plans to marry, the emperor wrote to his theater director with a jocular reference to Figaro’s plot: “The marriage between Laschi and Mombelli may take place without waiting for my return, and I cede to you le droit de Seigneur.”* Laschi performed an extraordinarily wide range of roles, defying classification as a singer. She must have had outstanding acting skills and a fine vocal technique, although she did not cultivate fioratura. The Mombellis left Vienna at Easter 1789. She died soon thereafter, perhaps in childbirth, having delivered a stillborn child the year before. *the fictitious right of a nobleman to bed any bride on his estate on her wedding night.

Mozart, “Restati quà . . . Per queste tue manine,” K. 540b, for Zerlina and Leporello in Don Giovanni, 1788. Da Ponte, libretto. This duet, added to the opera for the Vienna prodution, is the only other music besides that of the Countess that Mozart wrote for Laschi. By 1788 she was the court theater’s leading female singer, earning considerably more than the Germans (Cavalieri, who sang Elvira and Aloysia Lange, who sang Donna Anna). She was assigned the role of Zerlina because it was considered the principal female part. The 1787 premiere had featured as Zerlina Caterina Bondini, who was also Prague’s first Susanna. The role of Donna Anna gained prominence only in the 19th century. This duet is broadly slapstick and presents a knife-wielding Zerlina tying Leporello to a chair so that he can be properly “handled” by Masetto. Masetto never arrives, so Zerlina gleefully disciplines Leporello herself.

Martín, “Sereno raggio” for Amore in L’arbore di Diana, 1787. Da Ponte, libretto. Revealing yet another side of her stage personality from that of the tender Countess and the spirited Zerlina, Laschi took the role of the puckish Amore in this opera. The character appeared alternately as a woman and a man, which must have made considerable demands on her. According to the Kritische Theater journal von Wien, she was “Grace personified… ah, who is not enchanted by it, what painter could better depict the arch smile, what sculptor the grace in all her gestures, what singer could match the singing, so melting and sighing, with the same naturalness and true, warm expression?” In this little aria, another of Martín’s lyrical gems, Amore promises happiness to his most recent victims.

LOUISE VILLENEUVE (fl. 1771-1799)

She appears to have started her career in 1771 not as a singer, but as a dancer in Jean Georges Noverre’s ballet company in Vienna. By 1786 she was singing in Milan, and in June 1789 she returned to Vienna for her singing debut as Amore in Martín’s L’arbore di Diana. She successfully replaced Laschi, who had created the role, by virtue of “her charming appearance, her sensitive and expressive acting and her artful, beautiful singing” (Wiener Zeitung). She must have made Mozart’s acquaintance shortly after resettling in Vienna because he was soon composing substitution arias for her. First-rank singers frequently replaced arias in roles not originally written for them with pieces better suited to their voices; in Villeneuve’s case, these included arias she commissioned from Mozart. In August 1789 he gave her “Alma grande e nobil core,” K. 578, for Domenico Cimarosa’s I due baroni, and in Otober “Chi sa, qual sia,” K. 582, and “Vado, ma dove?” K. 583, both for Martín’s Il burbero di buon core. By the end of that year, Mozart was hard at work on Così fan tutte, in which Villeneuve was cast as Dorabella. In an inspired last-minute addition, Mozart wrote the aria “È Amore un ladroncello” as a kind of inside joke, alluding to Villeneuve’s debut role in Vienna. She sang alongside Ferrarese in Così, but there is no evidence, as has sometimes been stated, that the two were sisters. In the spring of 1791 Villeneuve left for Italy, where she continued to perform until at least 1799.

Mozart, “Ahí cosa veggio . . . Vado, ma dove?” for Madama Lucilla in Martín’s Il burbero di buon core, 1789. Da Ponte, libretto. Many fators argue for Mozart’s authorship of this recently discovered accompanied recitative to his “Vado, ma dove?” (see Cambridge Opera Journal, 2000), not the least of which is the way it prepares the aria. When it stands alone, the aria startles the listener with the intensity of its opening. The accompanied recitative, however, gradually builds the dramatic tension to where the beginning of the aria becomes the logical outcome of the emotional turbulence that precedes it. Madama Lucilla’s husband is on the verge of bankruptcy. What Lucilla doesn’t know is that she is partly to blame for having overspent. However, she is aware of the strained behavior of the other members of the household toward her. In the recitative, Lucilla reads a letter from her husband’s lawyer, pieces the story together, and resolves to save her husband. In the first part of the aria she expresses anxiety about how to accomplish her task, in the second she declares that love will show her the way.

Mozart, recitative “No caro, fa coraggio,” and Domenico Cimarosa, rondò “Quanto è grave il mio tormento” for Madama Vertunna in Pietro Alessandro Guglielmi’s La quakera spiritosa, 1790 This little known accompanied recitative (in neither Köchel’s thematic catalogue nor the complete works edition) was Mozart’s contribution to a pasticcio built around Guglielmi’s opera. Composed for Naples in 1783, the opera apparently needed drastic changes to make it suitable for Vienna seven years later. How Mozart came to compose a recitative to another composer’s aria within a third composer’s opera can only be imagined, but since there is a strong probability that Villeneuve sang the role of Vertunna, it is likely that she prevailed upon Mozart to improve her part. Cimarosa’s piece qualifies as an insertion aria rather than a substitution because it introduces new words instead of simply resetting existing text. In the recitative and aria, the character alternately requests that her beloved remain brave and steadfast, exclaims her own torment and misery, and demands that the heavens protect her beloved.

Album Details

Total Time: 76:00

Recorded: February 11, 12, 18, 20 in Bennett-Gordon Hall at Ravinia, Highland Park, Illinois

Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineer: Bill Maylone

Front Cover Photography: Nesha & Kumiko Fotodesign

Costume: Julia Needlman, Needlman Designer Custom Sewing

Graphic Design: Melanie Germond

Notes: Dorothea Link

© 2002 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 064