Store

Maud Powell (1867-1920) was America’s first classical music superstar: an international concert violinist of the first rank, a best-selling recording artist, a dynamo devoted to American composers and the belief that everyone deserves to experience great music performed at the highest level.

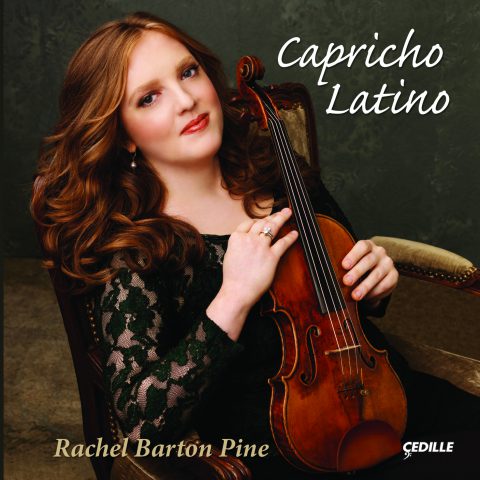

A kindred spirit, celebrated American violinist Rachel Barton Pine performs music dedicated to and arranged by Maud Powell. Some of the composers you know: Chopin, Dvorak, Sibelius. Others are yours to discover: Beach, Bauer, Burleigh, and many more.

Pine is among the first to perform Maud Powell’s transcriptions and music dedicated to her since Powell took the concert world by storm at the turn of the 20th century.

When Pine performed her Maud Powell tribute last year, the Washington Post declared, “Pine displays a power and confidence that puts her in the top echelon of recitalists. . . . Channeling the spirit of Powell, she played Dvorak with fire and passion . . . and gave Sibelius a sensational twist.”

Preview Excerpts

AMY BEACH (1867-1944)

PERCY ALDRIDGE GRAINGER (1882-1961)

ANTONÍN DVOŘÁK (1841-1904)

JEAN SIBELIUS (1865-1957)

MARION EUGÉNIE BAUER (1882-1955)

FREDERIC CHOPIN (1810-1849)

CARL VENTH (1860-1938)

SELIM PALMGREN (1878-1951)

SAMUEL COLERIDGE-TAYLOR (1875-1912)

ANTONÍN DVOŘÁK

H.P. DANKS (1834-1903)

HERMAN BELLSTEDT, JR. (1858-1926)

HENRY HOLDEN HUSS (1862-1953)

HARRY MATHENA GILBERT (1879-1964)

CECIL BURLEIGH (1885-1980)

Four Rocky Mountain Sketches, Op. 11

JULES MASSENET (1842-1912)

MAX LIEBLING (1845-1927)

J. ROSAMOND JOHNSON (1873-1954)

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletA Personal Note

Notes by Rachel Barton Pine

I’m frequently asked to name my favorite violinist. It’s virtually impossible – each of us has strengths and weaknesses. I admire certain performances and certain aspects of many players, and I draw inspiration from many violinists past and present. However, the violinist I most admire is definitely Maud Powell.

Despite being an avid researcher of violin music and history, I had never heard of Maud Powell until Karen Shaffer sent me a copy of Maud’s biography in 1995. I was fascinated to read about her remarkable and inspirational life. Reading on planes and in hotel rooms, I learned how she became the greatest American violinist in the late 1800s and early 1900s while also breaking so many social stereotypes: choosing to dedicate her life to her career; leading a string quartet of men; championing music by contemporary composers, American composers, women composers, and Black composers; and introducing classical music to numerous new listeners. She is often in the back of my mind today as I perform works by contemporary, women, and Black composers; as I perform rock and classical music in non-traditional venues; and as I give benefit concerts, support young string players, and strive for improvement and greater understanding in all of my interpretations.

Why is Maud Powell not better known today? I believe there are several contributing factors. Unlike Leopold Auer, she didn’t leave a pedagogical legacy. While Maud was committed to music education and encouraged every young violinist who came to her for advice, her touring schedule was too intense to maintain a teaching studio. Unlike Heifetz, she didn’t live into the electric recording era. And, unlike Wieniawski or Kreisler, she never wrote any original compositions.

After finishing her biography, I began learning some of her repertoire – works that she premiered, arranged, or recorded, and works written for her. Many of these gems have become staples of my recital programs. At the end of my recent performance in Washington, DC, Leonard Slatkin commented, ‘this music is wonderful! Maud Powell really was the female Fritz Kreisler.” Had I thought more quickly, I should have responded, “Actually, Kreisler was the male Maud Powell.” After all, Maud came first and was admired by Kreisler and all of his generation.

This album represents a slice of late Nineteenth/early Twentieth Century repertoire rarely heard these days. Miniature jewels like Humoreske, May Night, or Minute Waltz have an individual character that must be defined and demand a significant investment of the performer’s personality. Slower melodic works, such as those by Venth, Huss, and Johnson, call for indulgence in expressive shifts and creative rubato. The tone-painting of Burleigh and Bauer still sounds fresh a century later, and the Sousa Airs and Caprice on Dixie are brilliant American alternatives to the usual Carmen Fantasies and Paganini Caprices.

I hope this recording will open your ears to some masterful compositions, beautiful arrangements, and the art of one of the greatest violinists ever. I also hope that through this CD, the forthcoming printed collection of Maud’s music, the second edition of her biography, the reissues of her own recordings, and information posted on www.maudpowell.org, Maud Powell will finally receive the recognition she deserves as an artist and role model.

Notes: American Virtuoso: A Tribute to Maud Powell

Notes by Karen A. Shaffer

As the first great American violinist, Maud Powell (1867–1920) was a catalyst in the development of classical music throughout North America in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Born on the edge of the western frontier in Peru, Illinois, Powell carried the pioneering spirit in her blood. Her uncle John Wesley Powell, famed explorer of the Grand Canyon, organized the scientific study of the western lands and of the native American Indians as the powerful director of the U.S. Geological Survey and Bureau of Ethnology and founder of the National Geographic Society. Throughout her short life, Maud Powell boldly challenged convention, opened new avenues for others to explore, and left a legacy that endures to this day.

At a time when much of North America was still a vast wilderness and travel was dangerous and difficult, Maud Powell braved conditions that few would tolerate today in order to bring classical music to people who had never heard a concert. In the process, she pioneered the violin recital in America, inspired tens of thousands with her musical message, and set a new standard for violin playing.

Faced with audiences in remote hamlets and small towns who did not know what to expect from one of her recitals, Maud Powell understood that her ability to entertain was as important as her mission to educate. Powell possessed the largest repertoire of any violinist in her day. With a wealth of music in her fingertips, she won over unsophisticated audiences through her bold and engaging programming. On one tour in 1907–08, she opened with Grieg’s Sonata in G major, Op. 13, followed it with Vieuxtemps’s Concerto, Op. 31, and later played a group of smaller numbers; at other times, she began with the Schütt Suite, played the Arensky Concerto, and then smaller numbers. Her program included arrangements of St. Patrick’s Day, The Arkansas Traveler, and Dixie, which she used as encores. Powell grouped together smaller pieces to demonstrate musical qualities such as melody, rhythm, atmosphere, humor, coquetry, or dazzling technical display. Sonatas and concertos were received with appreciation, while with her short solos, she made her “most intimate and personal appeal to her audience.” (Miami Metropolis, February 22, 1912.)

Maud Powell believed it is the artist’s “duty” to reach her audience, even if they were only on the first rung of the ladder of understanding. “[H]er playing appealed to everyone,” wrote one critic. “Not only the musicians were lifted into ecstasies. In her last group she played a number of lighter compositions, exquisitely . . . and one listener said, ‘I know she did everything splendidly, but so much of it was above me; but the way she played [Schumann’s] ‘Traumerei,’ which I could understand, was the most wonderful thing I ever heard. I shall never forget it.’”

Powell understood that the key to educating the public to appreciate higher forms of classical music depended on her programming. “It’s largely a question of putting them in the right mood . . . things must be led up to properly; creating the proper contrasts and so on,” she noted. At a time when encores were demanded after each number on the program, she used short encore pieces to set the mood for the sonata or concerto that was to follow. “Before audiences in western cities I have played an old familiar Scotch melody and then swept into the best of Arensky. And the latter has always been appreciated,” Powell explained. In this way, Powell built a bridge of understanding spanning from the simplest melodies to the large, complex sonata forms. She asserted: “If I can have an audience of rag-time listeners to start with, I almost always feel sure that I can help educate them to love the other and higher forms of music. . . .”

As the first instrumentalist to record for the Victor Company’s Celebrity Artist series (Red Seal label) in 1904, Powell popularized classical music through her recordings. However, she refused to record “popular” music, arguing that people would find the tunes of the masters to be “just as pleasure-giving and vastly more interesting while their charm sinks deeper and lasts longer” once they became familiar with them.

The one exception was Powell’s recording of Hart Pease Danks’s “Silver Threads Among the Gold,” a sheet-music best-seller in the 1870s. After two years of prodding by the Victor Company, Powell agreed to transcribe and record it, saying: “I can square myself with the musician by saying — this is not for you but for the old people on ranches miles from a railroad.” Powell never allowed her transcription to be published and never played the piece in concert.

Maud Powell knew transcriptions were “wrong theoretically” but they fulfilled a purpose on her programs. She felt that “some songs, like Rimsky-Korsakov’s ‘Song of India’ and some piano pieces, like Dvořák’s ‘Humoresque,’ are so obviously effective on the violin that a transcription justifies itself.” Her transcriptions not only charmed her audiences, they introduced composers whose works they might not otherwise hear.

The pieces Maud Powell chose to transcribe are musical gems, illustrative of each composer’s musical character, period, style, and nationality in distilled form. Often, these were contemporary composers whom she knew personally, including Jules Massenet and Percy Grainger, along with Jean Sibelius and Antonín Dvořák, whose violin concertos she premiered in America.

Among Powell’s transcriptions featured in Rachel Barton Pine’s “American Virtuosa — Tribute to Maud Powell,” we can hear Massenet’s masterful ability to create a mood, to paint a scene with color, atmosphere, and fragrance; Sibelius’s humorous and characteristically unexpected pauses; Dvořák’s gift for rhythmic, unforgettable dance melodies and deeply emotional songs of haunting beauty; Grainger’s affinity with Irish dances — spirited, fun-filled, light, and joyous; Palmgren’s delicate tone-painting; and Chopin’s mastery of the piano and genius for miniatures.

In addition to music by European composers, Powell focused a great deal of attention on new works by American composers, then in a gestational period of development. “We have no distinctive utterance in invention or style. Speaking broadly of the nation at large, we are still in the ragtime stage — the first rung of the ladder of our musical expression,” she observed in 1913. Powell recognized that it would take time for American composers to transform the American experience into higher musical art forms and it would unfold as they realized the value of the material afforded by American history, literature, folklore, and its “wonderful natural beauties.” Composers felt honored by her attention, aware that her performances of their works brought with them significant public recognition. Many American composers dedicated works to her or sent her their recently published music or manuscripts in hopes of securing a public hearing. She included those she found of value in her concert programs.

Although few American composers had attempted writing violin concertos or even sonatas, Powell recognized that their smaller violin works meant progress in the evolution of American music. In her annual New York recital on October 21, 1913, Powell presented five works by American composers Marion Bauer, Edwin Grasse, Cecil Burleigh, Arthur Bergh, and Harry M. Gilbert as a group, four of which were dedicated to her.

When asked why she played so many American works, the violinist replied: “I have been criticized for this . . . but I invariably say that American artists owe it to their country to play the best examples of American music. How can we expect to have any national music, if someone does not play these works publicly? Foreign artists come over here and take enormous sums of money out of the country. They have not really served us vitally. They are not in sympathy with our institutions. They rarely play works by American composers. I must try to do what I can for American music.”

The music dedicated to Maud Powell by American composers and her own transcriptions of music by Americans, including African-Americans, nearly chronicles the evolution of American music.

It begins with relatively unsophisticated minstrel songs spanning the period 1850s to 1870s. This period embraces Dan Emmett’s toe-tapping “Dixie,” a minstrel song taken up by Civil War soldiers, which Herman Bellstedt, Jr., a cornet virtuoso in the Sousa Band, turned into a blistering solo violin showpiece for Maud Powell in 1905. Although she revised it substantially, Powell called Dixie “quite worthy of Paganini” and said she would not hesitate to play it anywhere. Ms. Pine has further enhanced this virtuosic piece with her own introduction along with some minor revisions.

H.P. Danks’s post-Civil War sentimental hearth-and-home song “Silver Threads Among the Gold” from 1873 presages the full-blown romanticism that marked the decades immediately before and after the turn of the 19th century. Expressive of this later era are the Romances for violin and piano composed by two of Powell’s earliest colleagues and friends Amy Beach and Henry Holden Huss, both pianists, and the Aria by Carl Venth, a violinist.

Powell and Beach first met and performed Beach’s evocative Romance in 1893 at the Women’s Musical Congress held at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Both musicians, at only 25 years of age, symbolized the rising influence of women in music. Beach went on to become one of America’s leading composers, while Powell became the leading American violinist.

Although Henry H. Huss and Powell were temperamentally quite different, Huss became Powell’s sounding board as she prepared works for performance, while he sought her opinion of his compositions. Powell’s first documented performance of this Romance was in her New York recital on January 11, 1906. New York critic Henry Krehbiel received the Romance as “a piece of sustained, emotionalized melody . . . with a rich and varied harmonic basis.”

Carl Venth’s Aria is the second of two pieces he dedicated to Maud Powell. Venth composed it around 1911 in Texas, where he made his mark as a violinist, conductor, composer, and teacher. Powell performed the Aria for Venth during her 1914 recital in Fort Worth. Venth admired Powell for possessing “every attribute of greatness, a warm tone, capable of every degree of shading, from the most dramatic intensity to the most joyful brightness, any amount of temperament and a big brain.” He claimed that her programming made her “perhaps the greatest of the great” because she ran “the whole gamut of the really worth while compositions, from the classics to the most modern.”

American patriotic fervor at the turn of the 19th century is mirrored in John Philip Sousa’s stirring marches. These were turned into the virtuosic “Fantasia on Sousa Themes” by pianist and vocal coach Emil Liebling for Powell to play as an encore following her violin solos with the Sousa Band on its 1905 tour of the British Isles. The Fantasia’s themes are drawn largely from Sousa’s operettas El Capitan and The Bride Elect, which were incorporated in his marches by the same names. The Fantasia ends with an excerpt from Sousa’s most famous march, “The Stars and Stripes Forever.”

In the second decade of the 20th century, violinist and composer Cecil Burleigh’s tone paintings of scenes from the American West in his “Rocky Mountain Sketches” explored new inspirational landscapes for composing uniquely American music. Maud Powell played “The Avalanche” from manuscript at her New York recital on October 2, 1913, where it was hailed for its emotional power and character. Powell visited Burleigh in his New York home to discuss his first violin concerto (which she performed) and “The Avalanche,” from “Rocky Mountain Sketches.” He considered it a “great honor” coming from “one of the truly great violinists of her time.” Powell shared Burleigh’s love for the American West, believing that the future of American music lay in that direction.

Harry M. Gilbert’s delicate Scherzo, “Marionettes,” reflected the humor and playfulness of American Broadway musicals, vaudeville, and operetta at the time. Gilbert, a native of Kentucky who held prestigious church organist posts in New York City, was as much at home with vaudevillians as he was as a piano soloist or as an accompanist for American opera singer David Bispham, cellist Pablo Casals, and violinists Kathleen Parlow and Maud Powell. Powell introduced Gilbert’s “vivacious” Scherzo in New York in 1911, describing it as “a quaint conceit, picturing in tone the antics of tiny marionettes.” A New York critic hailed the music as “thoroughly spontaneous and musical” and Powell happily recorded the work in 1912.

Perhaps Powell’s most satisfying experience in providing inspiration for an American composer occurred with Marion Bauer’s “Up the Ocklawaha.” Powell had repeatedly urged Bauer to write something for her, wanting Bauer to “do for the American composer what I have tried to do for the American woman violinist.” In early 1912, upon her return to New York City after a tour, Powell met Bauer in the street, took Bauer to her apartment and described her night trip through the Florida Everglades. Powell depicted the eerie boat journey through the swamp forest of gaunt, giant cypresses shrouded in Spanish moss. “She described it with such earnestness that I was deeply impressed with the picture which had been forming itself into the musical images in my mind ever since she had begun to talk,” Bauer recalled. “I went to my rooms and immediately set to work at the piece, having a theme knocking insistently at my head. And so, a few hours later, I went back to her and showed her the almost completed sketches. There were tears in her eyes when she handed it back to me and said, ‘It is just as though you had been there.’ So she played it and it was really hers.”

Bauer’s piece is the most advanced and forward-looking of all the compositions dedicated to Powell, distinctly of the 20th century — a highly sophisticated, impressionistic, evocative tone-painting that still sounds modern to the ear. Powell commented that she had “never experienced a more remarkable expression of color and picture drawing in music than this work” and noted that it is “so individual in its musical speech, penned with such sure intent, that it must hold a unique place in violin literature.”

Near the dawn of the 20th century, the music of African-Americans began to appear in classical music art forms. Maud Powell knew the Black composers trained in classical music who were involved in transforming their own heritage into popular song, musical theater, operetta, and classical music art forms — including Henry Thacker Burleigh, Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, and James Rosamond Johnson — all of whom were involved in the momentous discussion about the development of a distinctly “American” music within the context of European art forms.

Powell moved to fully integrate African-American music and musicians into the emerging American tradition of classical music. She dared to cross the color line by performing African-American spirituals in recital and by championing the violin concerto and other works of Afro-English composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor. Her advocacy helped gain legitimacy for the place of music by Black composers in classical music concerts in America. “Deep River” was included in the collection of Twenty-Four Negro Melodies transcribed for piano by Samuel Coleridge-Taylor and published by Oliver Ditson in 1905. Coleridge-Taylor transformed earlier Black melodies and rhythms into a more classical art form for piano. In fact, in his “Deep River,” only the four bars immediately following the opening measure of rolling chords are true to the original spiritual.

In 1910, Powell was inspired to transcribe “Deep River.” She knew that Coleridge-Taylor considered “Deep River” “the most beautiful and touching melody of the whole series.” Powell attributed the effectiveness of her transcription to the beauty of his setting, which she said she “only recast . . . in great haste.” When she performed “Deep River” during her New York recital in October 1911, critic Henry Krehbiel hailed it as “far and away the most effective bit of music based on American folk song which has yet been offered to the public, and the audience heard it with delight not unmixed with surprise.”

It was the first time a White solo concert artist trained in the European classical music tradition had performed an African-American spiritual in concert. Previous to this time, primarily Black ensembles and soloists had presented spirituals in concert. Powell recorded “Deep River” for the Victor Company on June 15, 1911, the first version ever recorded, giving it world renown.

J. Rosamond Johnson’s arrangement of “Nobody Knows the Trouble I See” for voice and piano was published in 1917. At that time, he was the director of the New York Music School Settlement for Colored People and was well known as an excellent singer and pianist and a successful composer who broke the color barrier with his popular songs written for musicals, operetta, and vaudeville. When Maud Powell knew him, Johnson was compiling and arranging two collections of African-American spirituals and folk tunes that were eventually published as The Book of American Negro-Spirituals and The Second Book of Negro-Spirituals in 1925 and 1926. Powell discussed with him his arrangement of “Nobody Knows the Trouble I See” and he expressed the hope that she might transcribe it for violin and piano. She did so in June 1919 as a surprise for Johnson in response to his request that she give an emergency benefit concert for the school. Powell’s full recital program concluded with her rendition of “Deep River” during which “faces took on a visible emotion.” She then played “Nobody Knows the Trouble I See” to the intense delight of everyone. She included this transcription in her fall 1919 programs, and it became the last piece she ever played in concert, just before she collapsed on stage of a heart attack in St. Louis in November. She dedicated her transcription to H. Godfrey Turner, her congenial, devoted husband and enterprising manager who fully shared her vision.

Rachel Barton Pine, a musical explorer in her own right, is among the first to perform Maud Powell’s transcriptions and music dedicated to her since Powell herself played them. She has performed many of these pieces in concert tributes to Maud Powell in Illinois and Washington, D.C. while also including them in her regular recital programs, to the delight of her audiences. Combining music with narrative, Ms. Pine’s special recital program, “A Tribute to Maud Powell,” offers an excellent perspective on the pivotal role and achievements of Maud Powell in American music history. As an inspiring performer and educator in the broadest sense, Ms. Pine is admirably carrying forward Maud Powell’s musical legacy with her very own special gifts.

Ms. Pine was the music advisor and editor for the forthcoming sheet music collection Maud Powell Favourites from which the music on this recording was drawn. The four-volume collection, to be published by HNH International Limited, contains extensive, detailed notes on all of Maud Powell’s transcriptions and music commissioned by or dedicated to her. For further information about the collection, please visit the Maud Powell Society’s web site at www.maudpowell.org. Maud Powell Favourites can be ordered through the Artaria website www.artaria.com.

Maud Powell’s own recordings include a number of selections found in Maud Powell Favourites. All four volumes of Maud Powell, The Complete Recordings, 1904-1917, Naxos Historical Series, Great Violinists, Vols. 1-4, Naxos 8.110961, 8.110962, 8.110963, 8.110993, can be ordered from www.naxos.com, www.amazon.com, or www.amazon.co.uk.com.

© 2007 Karen A. Shaffer

Karen A. Shaffer is the president and founder of The Maud Powell Society for Music and Education. She is the author of Maud Powell, Pioneer American Violinist and compiled the forthcoming sheet music collection Maud Powell Favourites.

Album Details

Total Time: 78:45

Producer: Judith Sherman

Engineer: Bill Maylone

Graphic Design: Melanie Germond

Cover Painting: Maud Powell (1918-1919) by Nicholas Richard Brewer. Oil on canvas. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of Joyce McFarland Dlugopolski (in memory of George A. Doole, Jr.) and the Maud Powell Society for Music and Education. NPG.2001.74

Photos of Rachel Barton Pine by Andrew Eccles

Photos of Maud Powell courtesy of the Maud Powell Society for Music and Education

Recorded: October 3, 4, 5, and November 1, 2006 at WFMT Chicago

Violin: “ex-Soldat” Guarneri del Gesu, Cremona, 1742

Strings:Vision by Thomastik-Infeld

Luthier (violin technician): Paul Becker

Steinway Piano – Piano Technician: Charles Terr

Mutes used on the recording:

La Fleurie by Franois Couperin* (wooden mute)

Twilight by Jules Massenet (rubber “Spector” mute)

Musette by Jean Sibelius (leather mute)

All mutes from the collection of Fred Spector

*La Fleurie is not on the CD but is available for download from web sites including iTunes, eMusic, Napster and other major digital distributors.

©2007 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 097