Store

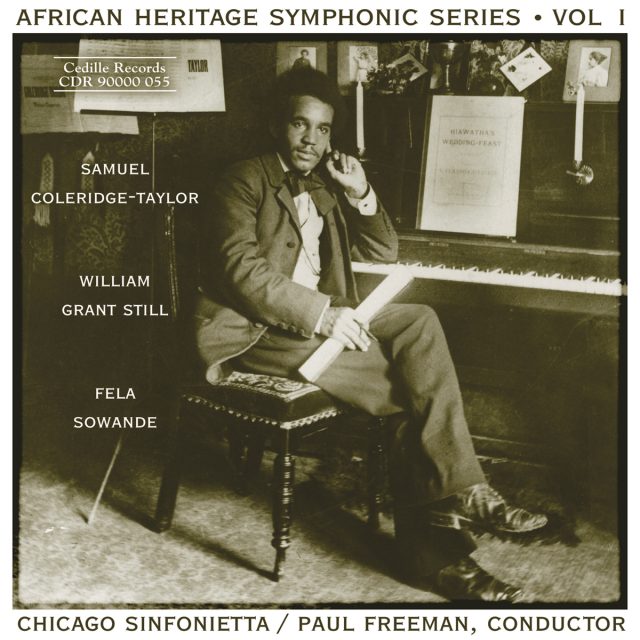

This recording is the first disc in an emerging three-CD series devoted to twentieth-century composers of African descent, a project inspired by CBS Records’ landmark Black Composers Series of the 1970s. Paul Freeman, artistic director and featured conductor for the long out-of-print CBS series, conducts the Chicago Sinfonietta for Cedille’s African Heritage Symphonic Series. Dominique-René de Lerma, chief consultant and program annotator for the CBS series, is writing the program notes for Cedille’s series. This recording was funded in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts to the Chicago Sinfonietta.

Best known for his serious choral masterpiece, Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast, Afro-British composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor is represented by two works in a lighter vein. “Danse Negre” from African Suite sounds like a rousing overture evocative of Broadway musicals of a later era. The work was inspired by the writing of Paul Laurence Dunbar, the celebrated African-American poet whom the composer knew and admired. Coleridge-Taylor’s charming, often balletic Petite Suite de Concert, Op. 77 was championed by England’s counterpart to Arthur Fiedler, Sir Dan Godfrey.

Nigerian Fela Sowande’s African Suite (three selections) from 1930, scored for string orchestra and harp, incorporates traditional Nigerian melodies and the influence of Ghanian composer Ephiraim Amu. The suite’s first movement, aptly named “Joyful Day”, is lovely and energetic, with a big-hearted opening that brings to mind Copland’s Appalachian Spring from 1944. Sowande was also an accomplished organist, schooled in the works of Bach and Handel, which perhaps accounts for the fugal orchestral writing in the “Nostalgia” movement. The delectable, folkloric movement titled “Akinla” adapts a melody from West African “highlife”, a spirited dance style that mixes African, Caribbean, and Western sonorities.

William Grant Still’s Symphony No. 1, “Afro-American”, evolved from blue-based sketches he wrote during the 1920s Harlem Renaissance while arranging for jazz ensembles. Freeman’s sultry, swinging interpretation is several minutes faster than competing CD versions. Freeman, who worked directly with Still on performances of the First Symphony and other works, says Still “always emphasized the ‘flow’ of the music, and faster tempos were often the natural outcome.”

Preview Excerpts

SAMUEL COLERIDGE-TAYLOR (1875–1912)

Petite Suite de Concert

FELA SOWANDE (1905–1987)

African Suite (selections)

WILLIAM GRANT STILL (1895–1978)

Symphony No. 1, "Afro-American"

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletAfrican Heritage Symphonic Series

Notes by Dominique-René de Lerma

Most of the United States’ early settlers were too occupied with other matters to be concerned with music, or felt that such a frivolity was irrelevant to the salvation of souls (exceptions were the immigrant Lutherans, Moravians, and domestic Psalm-singing Puritans). Such attitudes, no matter how qualified by the sentiments of later arrivals, mitigated an important role for music in much American life.

In time, however, as attitudes and conditions changed, there arose an anxiety that America would never have its own identifiable music; that anything of quality would have to be imported from Europe — Germany specifically (this was also true with the “mother country” from the time of Handel until Elgar). European musicians who visited the United States were received with honor, but none made the impact of Antonin Dvorák (1841-1904), who spent a few years on the faculty of New York’s National Conservatory of Music at the end of the 19th century — a school whose policy specified non-discrimination with respect to race, gender, disability, and financial status. While this Czech master might have encountered African-American spirituals before his arrival, he soon became very familiar with those sung to him by Harry T. Burleigh (1866-1949), a voice student at the Conservatory.

When questioned about native musical talent, Dvorák advised composers to look to indigenous roots, including the spiritual. He had done the same, as indeed had every composer of the period who sought an ethnic identity to distinguish their writings from the commanding ideas of Richard Wagner. Even before Wagner, non-Germanic composers had perused their local traditions, folklore, history, folk tunes, peasant dances and rhythms, the rhythm of their spoken language, and musical instruments within their heritage. By such means, Chopin, Falla, Bartók, Grieg, Vaughan Williams, Mussorgsky, and others found a new musical language. “Down-home” sources were idealized, a non-Wagnerian aesthetic was discovered, and a valid ethnic tradition was established.

Such was Dvorák’s suggestion to the culturally apprehensive Americans. Only a few took his sentiments to heart, but African-American students at the Conservatory saw the parallel, particularly those who came under Dvorák’s influence, including Will Marion Cook (1869-1944, who opened the doors of musical theater in New York to Black talents), Maurice Arnold Strothotte (1856-1937, who was already disposed toward ethnic styles from his student days in Europe), and Burleigh (who turned the oral tradition of the spiritual into that of published art songs, much as Brahms had done with his own north German heritage). Among these disciples, the impetus to “elevate” the folkloric was already in place. They understood that their heritage entailed far more than just minstrelsy and coon songs (not yet absent from our own contemporary pop culture). Rather, it was the profundity of the spiritual and dances of the common folk that would provide the rich soil from which an indigenous music could grow.

A second boost for African-American confidence came with the celebrated visits, not quite ten years later, by the extraordinarily gifted young Afro-British composer, Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (1875-1912). He never wrote ragtime, coon songs, or was engaged in minstrel shows. He was the esteemed composer of Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast (performed in Boston prior to his first American visit), one of England’s three most popular choral works (along with Mendelssohn’s Elijah and Handel’s Messiah). His tours were enormously successful and demonstrated to the African-American community what they had always felt: that there was a Black genius for creativity, and that their culture was deserving of as much dignity and respect as those which one more frequently encountered.

Although he was by no means the first of his race to follow these paths, William Grant Still (1895-1978) had profound admiration for Coleridge-Taylor and his music. He even tried to emulate his idol’s bushy hair-do, but Still came from a wide mixture of backgrounds, and his Native American, Anglo, and Hispanic ancestors endowed him with straight hair.

Although American sociology would consistently discount other elements of his ancestry — he was “Negro,” pure and simple — this cultural mixture was, in fact, central to Still’s identity. He was a harbinger of the miscegenation that had long been practiced in the United States, no matter the wishes of the female slave, and by those who escaped slavery by entering in association with Native Americans or other persons of color. His birth certificate identified only one race, and he never rejected that. But Still’s varied roots show clearly in his music, which is that of a richly integrated American.

In the 1920s, during the artistic explosion of the Harlem Renaissance, Still began to conceive of an idealization of the blues, which he knew quite well even apart from his professional association with “father of the Blues” W.C. Handy (1873-1958). Those 1920s sketches, written while he arranged for jazz ensembles, culminated with his 1930 First Symphony, subtitled the Afro-American.

The first movement follows the form that had been traditional since the mid-18th century: two themes presented, qualified, and restated. But the melodies Still uses are in the form of classic blues. Each consists of three four-bar phrases, basically harmonized by three chords. The sonority of the muted trumpet, following the brief introduction by the English horn, is reminiscent of this innovation in jazz ensembles of the same time. Its accompaniment is filled with contrasting layers of rhythms and instrumental colors. The harmony is ambivalent about major and minor mode. The theme is restated by the clarinet, with the strings imitating snapping fingers, and enhanced by new rhythmic and coloristic textures in commentary and response. The idea of the theme is extended as a bridge to the second theme, stated by the oboe. Again, the twelve-bar blues is the template. Another bridge leads to the restatement of this theme, now shared by the cellos and harp. The tempo picks up for explorations of implications from the first theme. The recapitulation of the two themes, in reverse order, ends the movement.

As is customary, the symphony’s slow movement comes second. Again we encounter two themes, both in the blues idiom, stated and repeated.

The minuet of the 18th-century symphony’s third movement gave way to other dance-influenced forms when the minuet fell out of favor. Here was the opportunity for the nationalist composer to call on dances from local traditions, such as Dvorák’s use of the furiant. Still opts for a vivacious, enthusiastic movement that restates its single theme in various guises. The blues is still there, but no longer contemplative.

Noble sobriety returns with the last movement, with fragments, extensions, and reminders of earlier material, particularly evident when the tempo quickens. The composer provided no story for the symphony, but the character of each movement exhibits his intent of expressing longing, sorrow, humor, and, in this last movement, aspiration.

It is not just the flavor of the tunes, the modes of the harmony, and moods of the movements that justify the work’s subtitle. Still’s concept of orchestration and instrumentation intensify the work’s distinctive colors. Other composers have used the bass clarinet and harp, but not within this context, and the employment of the marimba and banjo appears unprecedented in orchestral repertoire. If the aggregate sounds much like a film score, it must be noted that soon after completing this work, Still carried his sonic vocabulary to Hollywood, for such films as Pennies From Heaven and Lost Horizon, defining — or at least contributing to — the sound of film scores of the day (an influence that was felt abroad as well). If one is reminded of Gershwin, let it be known that each knew the other’s music. For proof, listen to “I Got Rhythm” in the entrance of the horns in the third movement.

With certainly no disrespect to Duke Ellington, Jelly Roll Morton, Count Basie, Jimmie Lunceford, Bessie Smith, or the many other remarkable talents that emerged during the period, it was Still who realized and culminated the “elevation” goals of the Harlem Renaissance, precisely with this symphony.

Still stood on the shoulders of the early blues musicians, finding there his point of relative departure. Coleridge-Taylor had no such model within his native environment. He knew of his father’s origin in Sierra Leone, but the young physician left London when his son was an infant, unable to secure the living he had hoped for. The child developed a yearning for the heritage that distinguished him from his British contemporaries. He learned the American dialect of that legacy through contacts with the African-American poet, Paul Laurence Dunbar, starting in 1896, and it was he who greatly stimulated the composer’s interest in Black culture. His desire to identify with minority interests was intensified by attendance at the 1897 concerts of the successors to the all-Black Jubilee Singers, who included Maggie Porter (1853-1942), a Fisk University student at the group’s inception and continuous member of the Jubilee Singers through that fifth and final tour of Britain. This orientation led Coleridge-Taylor to Longfellow’s Hiawatha epic. In 1898, the same year that the first of his three Hiawatha-based cantatas was performed, Coleridge-Taylor was stimulated by a Dunbar poem to write African Suite, originally for string orchestra. Coleridge-Taylor’s first of three visits to the United States, in 1904, gained him immediate contact with many leaders, including Harry Burleigh, who served as his baritone soloist; pianist Mary Europe, whose brother, James Reese Europe, would invigorate the French musical scene during the First World War; and Booker T. Washington.

Prior to his initial American visit, Coleridge-Taylor received and read E.B. Dubois’ The Souls of Black Folk. In a note of appreciation for the gift, he wrote that it was “about the finest book I have ever read by a coloured man and one of the best by any author, white or black.”

Coleridge-Taylor had begun studying the violin at age five and entered the Royal College of Music in 1890. His classmates included Vaughan Williams and Gustav Holst. Overt support came from Elgar in 1898, who described Coleridge-Taylor as “far and away the cleverest fellow going amongst the young men.”

Danse Negre is the last of the four movements that make up the African Suite, Op. 35 (proceeded by Introduction, A Negro Love Song, and Valse). It is basically in the same form as that employed in the first movement of Still’s Afro-American Symphony, except that a third theme, quite sentimental, is introduced in the middle section and replaces the second theme in the recapitulation.

Coleridge-Taylor wrote his Petite Suite de Concert, Op. 77, just over a year before his early death. It has been noted that an intensified schedule as a most popular composer and conductor encouraged the creation of more works in a lighter vein than prior to 1900. That is certainly true with this suite, yet it has an undeniable charm and elegance that is immediately obvious with “La caprice de Nanette.” Coleridge-Taylor biographer, Geoffrey Self (The Hiawatha Man, 1995) identifies Schumann as the inspiration for the first melody, and Sir Edward German’s music as the model for the middle theme. The second movement, “Démande et réponse,” is a gentle waltz, based partly on the music from an earlier monodrama. Of the four movements, this immediately became the most popular. Third is “Un sonnet d’amour,” which Self accurately characterized as “balletic.” The finale, “La tarantelle frétillante,” draws on the same earlier work as the second movement. As with its companions, it is in ternary form (ABA). The suite was first performed on April 20, 1911, with the composer conducting the Bournemouth Municipal Orchestra, and subsequently championed by England’s counterpart to Arthur Fiedler, Sir Dan Godfrey.

Fela Sowande (1905-1978) was born in Nigeria and began his musical studies there. He completed these at London’s Trinity College and Royal College of Organists. His career was most varied. After briefly studying engineering, he returned to music, but in many aspects. He was an accomplished organist and had been nurtured in works of Bach and Handel while still in Nigeria. In London, he came to know recordings of Art Tatum and Fats Waller, and performed with J. Rosamond Johnson and Adelaide Hall. His 1936 performance of Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue may well have been the first in England. Following the Second World War, he was named music director of the Nigerian Broadcasting Service and, in 1962, established a music school in Nsukka. Faculty appointments at Howard University, the University of Pittsburgh, and Kent State University followed his tours in the U.S.

In his lectures and teaching, Sowande encouraged the acculturation of Nigeria’s indigenous music, well exemplified in the African Suite of 1930, based in part on traditional Nigerian melodies and in part on music by Ghana’s musical patriarch, Ephiraim Amu (1899-1995). Of the original five movements, three — the original first, second, and final movements — are heard here. First is “Joyful Day” (in which some repeated material has been excised on this recording). Second comes “Nostalgia,” in which Amu’s material is used. The concluding item is “Akinla,” which makes reference to a popular “highlife” melody.

When Sowande conducted the New York Philharmonic in his Nigerian Folk Symphony in 1964, a critic lamented that it sounded more European than Nigerian. What he missed was that, although the orchestral sonority was certainly not rooted in Africa, the rhythms, scales, and melodies were idealizations of Nigerian sources. Sowande thus joined the other nationalists, following the same process traveled by William Grant Still.

Lawrence University Professor of Music, Dominique-René de Lerma began his teaching career in 1951 in Miami and has served on the faculties of Indiana University, Morgan State University, the University of Oklahoma, The Peabody Conservatory of Johns Hopkins University, and Northwestern University. He founded the former Black Music Center at Indiana University and has served as director of the Center for Black Music Research in Chicago. His home page may be found at www.musicbase.org/DEL002/htl.

Album Details

Total Time: 51:26

Recorded: May 23 & 24, 2000 in Lund Auditorium at Dominican University, River Forest, Illinois

Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineer: Bill Maylone

Cover: Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (Courtesy of Jeffrey Green, England)

Design: Melanie Germond

Notes: Dominique-Rene de Lerma

©2000 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 055