Store

Store

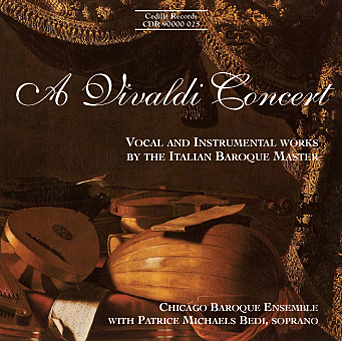

A Vivaldi Concert

Chicago Baroque Ensemble, Patrice Michaels

Anita Miller-Rieder, John Mark Rozendaal, David Schrader

When people think of Vivaldi, they think of concertos, which represent only about half of his nearly 800 compositions. Vocal music? Mostly forgotten. Vivaldi recordings, though voluminous, comprise many predictable collections of similar works — flute concertos, violin concerto, and so forth.

A Vivaldi Concert, performed by the Chicago Baroque Ensemble with guest artist Patrice Michaels, soprano, opens a unique vista on the Venetian composer. It’s an invigoratingly diverse program of Vivaldi’s vocal and instrumental works, none of them over-recorded.

“We looked at all approaches to programming Vivaldi on disc and took the one less traveled by,” said Cedille producer James Ginsburg, paraphrasing a Robert Frost poem, “And that makes all the difference.” The program of motets, concertos, cantatas and sonata unfolds through a symmetrical sequence of varied musical textures, moods, and instrumentation for and entertaining (and generous) 78-plus minutes of music.

This variety is a truer reflection of what a concert in Vivaldi’s day would have sounded like — and how the Chicago Baroque Ensemble programs its concerts — compared to today’s typically homogeneous concert programs, according to the ensemble’s artistic director John Mark Rozendaal, who also wrote the CD booklet notes.

Variety was the goal even among the selection of vocal pieces; the sacred motets exhibit a relatively simple vocal style, while the cantatas on the theme of romantic love allow for a more freely expressive vocalism. The first motet is characterized by a pure, angelic soprano sound, while the second is darker, moodier.

The first cantata, “All’ombra di sospetto,” RV178, features flute while the second cantata, “Lungi dal vago volto,” RV680, features violin. For further variety, keyboardist David Schrader plays chamber organ rather than harpsichord in the motets, which were intended for church performances.

Rozendaal’s notes set the stage by depicting the artistic vitality of 17th-century Venice in modern terms: the city was “the Hollywood of Europe, the center of a powerful entertainment industry and a playground for the continent’s beautiful people.” Music-making was everywhere — “in the churches, the opera houses, the palaces of the ambassadors, in the streets and canals.” And one of the key power-lunchers was Vivaldi, vain and temperamental, a “one-man music factory.”

Preview Excerpts

ANTONIO VIVALDI (1678-1741)

Motet: Nulla in mundo pax sincera, RV630

Concerto in D-minor for Strings, RV128

Cantata: All ombra di sospetto, RV178

Cello Sonata in B-flat, Op. 14, No. 4, RV45

Cantata: Lungi dal vago volto, RV680

Concerto in G-Major for Flute and Strings, RV436

Motet: Longe mala, umbrae, terrores, RV629

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletA Vivaldi Concert

Notes by John Mark Rozendaal

During the seventeenth century, Venice was the Hollywood of Europe, the center of a powerful entertainment industry and a playground for the continent’s beautiful people. In the course of generations of cultural exchange, the works of Venetian composers and artists were constantly in demand in Northern cities, while Northerners traveled to Venice to study or to launch careers. All of this cultural activity was supported by both the fabled wealth of the Venetian nobility, and the constant traffic of rich and noble tourists.

Visitors to Venice were stunned not only by the visual splendor of the city floating on the lagoon, but by the ubiquitous and excellent music-making. It was everywhere — in the churches, the opera houses, the palaces of the ambassadors, in the streets and canals. “It was evening, and the canal where the Noblesse go to take the air, as in our Hyde-park, was full of ladies and gentlesmen. . . . Here, they were singing, playing on harpsichords, and other music, and serenading their mistresses . . .” (John Evelyn, June 1645). “There’s hardly an evening when there’s not a concert somewhere; the people rush along the canal to hear it as if it were for the first time. The infatuation of the nation for the art is inconceivable.” (Charles de Brosses, 1739) “The instant I got to the inn a band of musicians consisting of two good fiddles a violoncello and female voice stopt under the window and performed in such a manner as would have made people stare in England, but here they were as little attended to as coalmen or oysterwomen are with us.” (Charles Burney, 1770)

During the first forty years of the 18th century one of the most powerful forces in this prospering industry was a vain, temperamental, athsmatic, red-haired priest named Antonio Vivaldi. Although he is principally remembered today for his many concertos for violin, and other instrumental works written for the famous female virtuose of the orphanage of the Ospedale della Pietà, Vivaldi actually worked in a wide variety of genres in the course of a varied international career. In four decades this one-man music factory produced no less than 750 instrumental and vocal compositions, including liturgical settings, chamber cantatas, and not less than 55 operas.

These works were performed by Vivaldi himself, a noted virtuoso on the violin, by his students at the Ospedale della Pietà, and by visiting artists of the highest rank (including the Dresden violinist Pisendel); in all of the major opera houses of Italy, as well as those of Prague and Vienna, in the homes of nobles and ambassadors, in the churches of Venice, and in the concert halls of Rome and Paris; through the sale of manuscripts and through publications in Amsterdam and Paris, they reached England (Handel’s librettist, Charles Jennens, collected them) as well as the court of Wiemar where they came to the attention of J.S. Bach.

Vivaldi’s sacred motets are concertos for the voice, bringing the brilliance and virtuosity of opera singing into the church. The texts are moody, non-liturgical latin doggerel, always ending with an Alleluia. The two motets on this CD illustrate Vivaldi’s ability to fill the boiler-plate formats with strikingly different materials. The dramatic Longe mala, umbrae, terrores, with its low vocal tessitura set in the somber key of g-minor, darkly depicts a world of horrors relieved only by the “dew of Heaven.” Conversely, the bright, lilting E-major arias of Nulla in mundo pax sincera suggest a garden of delights where seductive beauty conceals the poison of sin.

The secular solo cantata (a quite distinct entity from the German sacred chorale) was one of the most popular and widespread genres in Italian music in the Baroque era. Vivaldi’s works in this form are representative of the early eighteenth century repertoire. Following the poetic reforms of the Arcadian Academy of Rome, the texts are monologues based on the pastoral themes of “love, nature, illusion, love of nature, the nature of love, the illusion of love, the nature of illusion and so forth.” (L.G. Clubb) The opening recitative of Lungi dal vago volto is particularly notable for its bizarre harmonic progressions expressing the shepherd/narrator’s confused emotions.

The solo sonata for a single instrument with continuo accompaniment rivaled the cantata for the attention of composers, and easily outran it in the public sphere. Whereas most of the cantata repertoire survives only in manuscript, scores of sets of sonatas were published often in beautiful prints by French and dutch engravers. The ‘cello sonata is the only work on this recording which was published in Vivaldi’s lifetime. Vivaldi’s set of six ‘cello sonatas, published as his Opus XIV, in Paris circa 1739, include some of his finest, most imaginative chamber music, and the best ‘cello solos of the period.

During Vivaldi’s lifetime the transverse flute, in its recent French redesigned form, gradually replaced the recorder as a virtuoso solo instrument. Vivaldi’s first concertos for traverso are actually rearrangements of his earlier concertos for recorder. The present G-major concerto was apparently an original composition for flute, possibly composed after 1728, when the Ospedale’s oboe teacher, Ignazio Sieber, was reappointed to teach the flute.

Vivaldi’s music intrigues its hearers today, as it did from the first, by means of its startlingly original use of instrumental ensembles, as well as its innovative logical structure. Vivaldi found a new way of constructing a large-scale composition by extrapolating one musical thought after another from the potent seed of an opening motif.

This type of motivic development may be what J. S. Bach had in mind when he asserted that Vivaldi’s music had taught him “musical thinking.” This lesson effectively set the course for European music-making for nearly two centuries. Sebastian Bach taught this same musical thinking to his sons Carl Philipp Emanuel and Johann Christian, who in turn taught Mozart and Beethoven, who probably never knew the debt they owed to the then-forgotten red priest of Venice. In a last irony, Vivaldi’s death and burial eerily anticipated that of Mozart fifty years later: In 1741 Antonio Vivaldi died in Vienna, penniless and unmourned, his final resting place unrecorded.

Album Details

Total Time: 78:50

Recorded: May-Aug, 1995 at St. Lukes Church, Evanston, Illinois

Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineers: Bill Maylone and Lawrence Rock

Engineering Assistant: Jack Kelley

Cover: Musical Intruments with Statuette (detail), Evaristo Bachenis (1617-77). Accademia Carrara, Bergamo

Design: Cheryl A Boncuore

Notes: John Mark Rozendaal

©1995 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 025