Store

Store

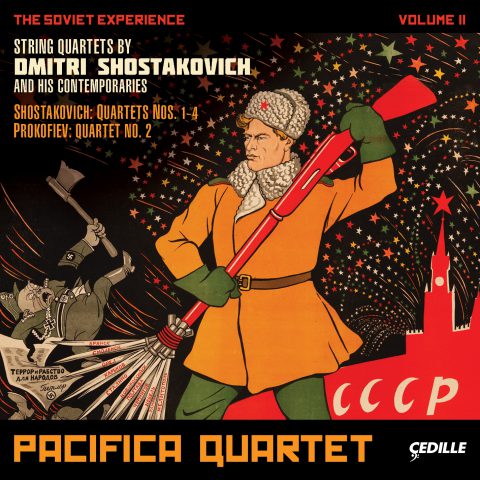

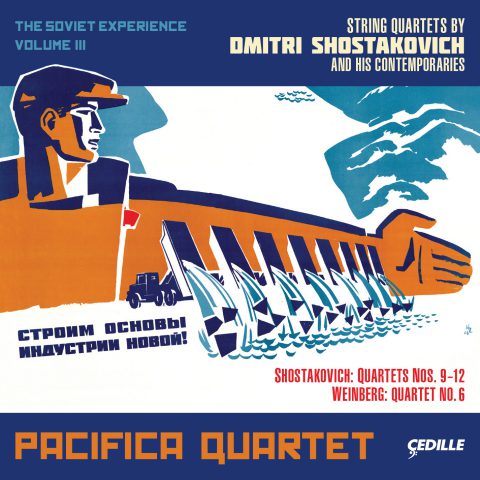

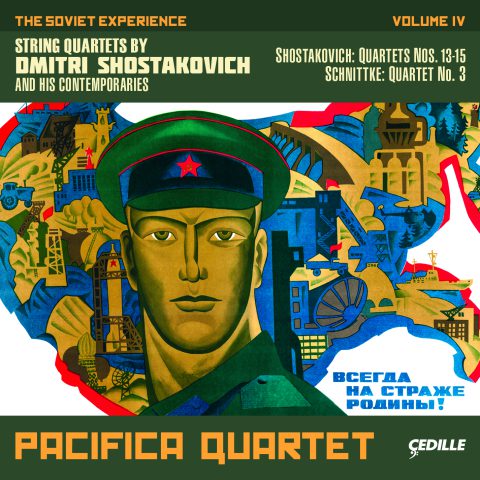

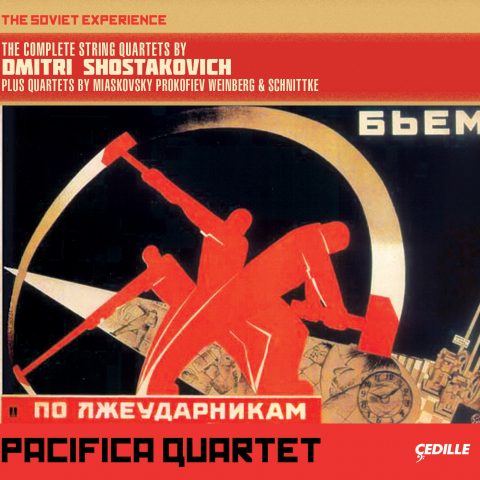

The Soviet Experience Volume I: String Quartets by Dmitri Shostakovich and his Contemporaries

This is the first installment in the Pacifica Quartet’s highly anticipated, four-volume CD survey of the complete Shostakovich string quartets: The Soviet Experience: String Quartets by Dmitri Shostakovich and his Contemporaries. The Soviet Experience is the first Shostakovich quartet cycle to include works by other important composers of the Soviet era, adding variety and perspective to the listening experience. This superbly performed series of audiophile recordings, produced and engineered by multiple Grammy Award winner Judith Sherman, will appeal to everyone interested in great Russian music of the 20th century. It’s also a great value: each two-CD installment is priced as a single CD.

Shostakovich’s intense String Quartet No. 5 (1952) introduces many characteristics that would become common in his later quartets. The String Quartet No. 6 (1956) holds surprises beneath its outwardly untroubled themes. The remarkably inventive and compact String Quartet No. 7 (1960) signals a significant stylistic change in the composer’s quartet writing. The deeply personal String Quartet No. 8 (1960) is the best-known quartet in the entire cycle. Nikolai Miaskovsky is the only major Soviet composer who was also a member of the pre-Revolution generation of Tchaikovsky and Rimsky-Korsakov. His masterfully written String Quartet No. 13 (1949) demonstrates great ingenuity and craftsmanship within a conventional harmonic language.

The Pacifica Quartet performed the complete Shostakovich cycle to great acclaim in New York and Chicago and at the University of Illinois in Urbana, Ill., during the 2010‚Äì2011 season. The Chicago Tribune said, “The remarkable Pacifica Quartet . . . coaxed the music’s unfathomable sorrows, fleeting joys and macabre humor to the surface as if creating it on the spot.” The New York Times called the Pacifica “enterprising and eloquent” and said its Shostakovich installments were “beautifully and powerfully played.” The Pacifica has been demonstrating its prowess with Shostakovich to concert audiences far and wide by performing the Quartet No. 8 on its tour program. The Denver Post said the ensemble “delivered rawness, power, and sensitivity in an authoritative performance that was profoundly haunting and moving.” Canada’s Globe and Mail said, “The Shostakovich . . . was memorably engaged at every layer and level of its discourse.”

Preview Excerpts

DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH (1906–1975)

String Quartet No. 5 in B-flat major, Op. 92

String Quartet No. 6 in G major, Op. 101

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletThe Soviet Experience: Volume l

Notes by William Hussey

Dmitri Shostakovich… is generally regarded as the greatest symphonist of the mid-20th century…

— David Fanning & Laurel Fay

Grove Music Online

Thus begins Grove’s entry for Shostakovich, and properly so. Dmitri Shostakovich (1905‚Äì1974) is most widely known as a symphonic composer. Certainly his fifteen symphonies, a large number by 20th-century standards, have made an indelible mark on the orchestral repertoire because of their powerful musical content, as well as their political and historical context. Although he wrote an identical number of string quartets, it is only in recent years that these have attained an equal standing in the chamber music canon.

What distinguishes Shostakovich’s quartets from his symphonies is, on one level, obvious. The string quartet is a more intimate genre compared to the large numbers involved in a symphonic performance; but, with Shostakovich, there is never just one level. Performances of his symphonies were large public events in Soviet Russia, intensely scrutinized by officials who controlled his personal and professional fate. The informal nature of the string quartet allowed for private performances, sometimes only for close friends within his own home. So the quartet form became a useful outlet to the composer when the political climate was not conducive to public appraisal of his music. For this reason, many find in his works for small ensembles a more personal reflection of Shostakovich and his times.

It is difficult to convey the significance of Shostakovich’s monumental contribution to the string quartet repertoire. From a historical stand-point, they are glimpses into the Soviet era through the eyes of an individual artist who lived his entire adult life during that time.From a musical standpoint, they form, arguably, the greatest quartet cycle of the twentieth century. It is virtually impossible for the informed performer or listener to separate these two perspectives as it is for so many of his works — a quality that continues to generate conflicting interpretations and arguments over the composer’s intentions, as well as over the value of his work. Of course, we can never know with certainty what Shostakovich’s own perspective was; and perhaps, as with great poetry, this resultant ambiguity becomes a source of his music’s appeal. Those who struggle to understand fully this man and his music will find his string quartets a delicacy that evokes the composer’s personal self more than his other music.

From October 2010 to February 2011, the Pacifica Quartet performed the complete cycle of Shostakovich’s string quartets to critical acclaim in Chicago and New York, and at the University of Illinois, Champaign-Urbana. The Soviet Experience: Quartets by Shostakovich and his Contemporaries includes the complete quartets by Shostakovich plus quartets by other composers active in the Soviet Union during his lifetime. This first volume contains Shostakovich’s Quartets Nos. 5‚Äì8 along with the final string quartet by his older contemporary, Nikolai Miaskovsky (1881‚Äì1950).

Dmitri Shostakovich: String Quartet No. 5 (1952)

The Soviet Union emerged from World War II as a world power, but one with a countryside devastated by war, an economy in tatters, and a death toll estimated at almost 24 million. With the end of hostilities, official scrutiny for the arts, which had eased during the war, was reasserted with strict cultural controls hammered down upon the Writers and Theatrical Unions in 1946, the year Shostakovich’s Third String Quartet was premiered. In 1948, official decrees would condemn Shostakovich, Prokofiev, and Miaskovsky, among others, as “formalists” whose music strayed from Socialist Realist doctrine. Just as when Shostakovich was vilified for his opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk in 1936, the political ramifications for the composer were disastrous. He was fired from his teaching positions at the Leningrad and Moscow conservatories and many of his works were removed from the officially accepted repertoire. Although they would be reinstated later, for many years most performers were shrewd enough to avoid programming works by someone declared an “enemy of the people” even after the ban was rescinded.

Survival for Shostakovich meant a necessary output of music for propaganda films and patriotic oratorios, but he would continue composing for himself, holding these works for performances at a later date when official doctrine would permit. Among these pieces were his First Violin Concerto, the song cycle From Jewish Folk Poetry, and his Fourth and Fifth String Quartets.

Shostakovich dedicated the Fifth to the Beethoven Quartet, who were celebrating their thirtieth anniversary as an ensemble. Since his Second Quartet, the premiere of each new Shostakovich quartet was reserved for the Beethovens, a tradition that would continue through the Fourteenth. Along with the members of the Borodin Quartet, the Beethoven players remained loyal to the composer during these difficult times, performing his Piano Trio and Piano Quintet with Shostakovich on tour when other performance opportunities were closed to him.

The support of these musicians, as well as of other close friends, was essential to Shostakovich during this time of isolation. His composition student Galina Ustvolskaya was one such valuable confidant. It was she who remained with him during the depression he experienced following the premiere of his oratorio Song of the Forests, a piece the composer was greatly ashamed of for its glorification of Stalin’s post-war plans. Equally supportive of her work, Shostakovich would prominently quote Ustvolskaya’s Clarinet Trio in his Fifth Quartet (and later in his Suite on Texts of Michelangelo Buonarroti). Since Ustvolskaya’s Trio would not be published until 1970, its quotation in the Fifth Quartet was known to only a few, suggesting the private and intimate relationship they shared at this time. The quotation itself is characterized by a descending third and several repeated notes followed by two additional falling thirds.

Musically, the Fifth Quartet initiates many characteristics that would become common in Shostakovich’s later quartets, including an unusual number of movements (in this case, three instead of the traditional four) and melodic similarities between movements that are performed without a break. Its sonata-form opening movement embodies conflict, in direct opposition to Soviet cultural dictates of the time, as the violins and cello initiate several short chromatic ascents that are answered by the viola with a dotted-rhythm motive that obscures the home key. This conflict bursts into a violent passage that artfully evolves into a lyrical, waltz-like second theme only to be opposed at its conclusion by simultaneous triple and duple rhythms. These two themes are repeated, as is common in a traditional sonata exposition, and are followed by further conflict in the ensuing development. The first quotation of Ustvolskaya’s Clarinet Trio appears as the development reaches its climax, serving as a calming influence that leads to a subdued and condensed recapitulation of the initial themes. The coda is dominated by a soaring version of the Ustvolskaya melody in the first violin (which has become the source of many programmatic interpretations for this movement ever since the quote was identified). The movement concludes with a pizzicato recollection of the opening’s conflicting motives as the first violin sustains a high F that will connect the first and second movements.

In the second movement, the viola enters below the first violin’s F with a motive similar to the viola line that opened the quartet. Soon these two instruments join together to play an ethereal melody two octaves apart that will accompany sorrowful solos in the second violin and cello. The austerity of this opening section slowly evolves into what Judy Kuhn, author of Shostakovich in Dialogue: Form, Imagery and Ideas in Quartets 1‚Äì7, calls an “oasis of tenderness” that fluctuates between the major and minor modes. These two sections return in a transformed and abbreviated form, as is common for Shostakovich, and the elusive coda is anything but conclusive as fragments of the opening return in the same violin/viola setting over a longing melody in the cello’s highest register. Within this movement, many analysts have identified allusions to other works by the composer, some of which were either withheld or banned from performance at this time. Given the quartet’s historical context, this sparsely textured movement may be a reflection of Shostakovich’s physical and emotional isolation at the time.

The Fifth Quartet’s third and final movement is remarkable in many ways, the most striking of which is its connection to the previous movements. Its initial bars seem to function as a transition from the second movement, but this material becomes the subject of the finale’s subdued conclusion, a similar structure to that used in movements one and two. The melody the viola plays to begin the finale is again related to the previous opening viola lines, both of which begin with what many have heard as variants of the composer’s DSCH motive, derived from the German transliteration of his name. Shostakovich introduced his “autobiographical” motive (in its “pure” form) publicly in his next composition, the Tenth Symphony (he initially withheld the Fifth Quartet from public performance), and, as we shall see, the motive dominates his Eighth Quartet. (See note on the Eighth Quartet for a detailed explanation of the DSCH motive.)

After the introductory passage, the movement proceeds in sonata form like the first. This time, Shostakovich reverses the character of his two themes, using a leaping, waltz-like first theme and a chromatic, stepwise second theme. Once again, the Ustvolskaya quotation appears at the development’s high point, now doubled in violin octaves against the low-register voicings of viola and cello. This leads into a recitative-like restatement of the first theme with the Ustvolskaya melody again functioning as a soothing contrast to the conflict of the development. As with the first two movements, the sonata’s two themes are shortened in their return, followed by a gentle ending that recalls the movement’s opening bars.

Dmitri Shostakovich: String Quartet No. 6 (1956)

Completed at the end of August 1956, the Sixth Quartet came at a vastly different time than the Fifth. Stalin’s death in 1953 would begin a period in Soviet history commonly called “The Thaw” (after Ilya Ehrenberg’s eponymous 1954 novel) that saw an easing of cultural restrictions and greater engagement with the West.

For Shostakovich, these changes were especially welcome, allowing works withheld from performance to be heard publicly, including the Fourth and Fifth Quartets (the Fifth was actually premiered a month before the Fourth). His well-received Tenth Symphony would come in 1954, ending a nine-year hiatus from the genre, but his first attempt to revive his condemned opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk would be denied, showing that previous policy had not been entirely abandoned.

The most significant personal event for Shostakovich at this time was the unexpected death of his wife Nina in December 1954. Although their relationship had been tumultuous at times, their love for and dependence upon one another was unquestioned by those who knew them. Shostakovich’s son, Maxim, related the devastating effect his mother’s death had on his father, citing it as one of the few times he saw his father cry. She had often served as a buffer between the composer and the many outside influences, both in support and in conflict, with which he had to contend. To make matters worse, Shostakovich’s mother would pass away less than a year later.

Not long before composing the Sixth Quartet, Shostakovich remarried. By most accounts, he proposed to Margarita Kainova shortly after they met, despite her being seventeen years his junior. (He had previously proposed to his student Galina Ustvolskaya and been refused.) Shostakovich wrote the Sixth Quartet during the initial jubilant months of his new marriage, ending the creative drought that had followed the Tenth Symphony. Unfortunately, this marriage quickly turned sour as Kainova’s lack of compatibility with family and friends and dislike of the composer’s music led to a seemingly inevitable divorce three years later.

In contrast to the progressive Fourth and Fifth Quartets, the Sixth, with its four-movement structure and lyrical themes, appears at first glance to represent a return to tradition, particularly in the first movement. While other composers were testing their new artistic freedom, Shostakovich appeared to take a non-confrontational approach with this quartet, perhaps as a result of his early marital bliss or as an attempt to write in accord with his new wife’s more conservative tastes. (Although there is no official dedication, the composer told friends he wrote the work for his fiftieth birthday.)

Reception of this quartet has changed greatly as many surprises have been discovered underneath its outwardly untroubled themes. Opening with repeated Ds in the viola (perhaps symbolizing the composer’s name: D ‚Äì D = Dmitri Dmitriyevich), the sonata-form first movement has a lyrical primary theme in G major followed by a more subdued second theme beginning with a long-short rhythm in the ensemble punctuated by solos from the first violin. (Shostakovich used a similar thematic structure in his First Quartet, another work known for its lighter lyrical melodies; author Sigrid Neef has identified similarities between these themes and that of a children’s song Shostakovich wrote for the film The Fall of Berlin in 1949.) When the themes return after the development, however, the first theme is disguised in a lower register with a vastly different accompaniment, sounding more like a continuation of the development than a recapitulation of the opening. To further confuse the matter structurally, the second theme returns in an unexpected E-flat minor. The opening theme then appears in its original key and setting, suggesting a “reverse recapitulation” in which the original themes are restated in opposite order, a structural technique often found in Shostakovich’s sonata-form movements.

The second movement reflects the straightforward thematic nature of the first, exploring what Sarah Reichardt, author of Composing the Modern Subject: Four String Quartets by Dmitri Shostakovich, describes as “various possible scoring per-mutations allowed by the quartet medium.” Set in a varied rondo form (ABA ‚Äì C ‚Äì ABC) the expected final A section is replaced with a return of the chromatic C theme. The third movement is a passacaglia, a contrapuntal writing style of variations over a repeated bass line found in many Shostakovich works. The bass line is stated initially in the cello with the other instruments entering, one at a time, with each successive bass repetition. The fifth variation introduces a four-note motive whose first three notes repeat the same pitch and descend to the fourth; this will become the accompaniment motive to a subsequent interlude in the passacaglia. Here the first violin performs a soaring melody in G-flat major before the passacaglia bass returns, now doubled in the viola below an ornamented version in the first violin. One final variation follows with fragmented four-note motive statements from the interlude.

The finale, as is often the case with Shostakovich’s works, seems to unite elements from previous movements and even previous works. Its initial theme is in a triple meter like the second movement, and begins with an inverted version of the first movement’s primary them. The secondary theme changes to a quadruple meter, using the same motive in its original form. The first theme returns, setting up a sonata-rondo form followed by a development featuring a return of the passacaglia bass line, a technique heard previously in Shostakovich’s Second Piano Trio and Third String Quartet. The second theme follows, now muted in the viola, and the primary theme closes the quartet, first in a quadruple meter but eventually returning to the original triple meter for the movement’s conclusion.

The most remarkable aspect of the Sixth Quartet is the closing figure used to end all four movements. Celebrated Shostakovich scholar David Fanning notes that the first harmony of this closing figure uses the notes of Shostakovich’s personal motive, DSCH, when the cello changes the chord by moving from A-flat to E-flat. Having appeared for the first time in its more recognizable melodic form two years earlier in the Tenth Symphony, it’s harmonic version in this recurring conclusion adds a hidden personal touch that the composer may have shared with a few close friends (whose public comments on the quartet and this figure seem to hint at this aspect when read in retrospect).

Most scholars note the unifying function this cadence serves and its somewhat conventional harmonic material as another sign of the quartet’s traditional leanings. In Sarah Reichardt’s estimation, the effect of this figure has much more to do with its surrounding material. In the first and second movements, the figure appears after the home key is confirmed, functioning as a tag on the end of the movement in the respective keys of G major and E-flat major. The third movement, in B-flat minor, ends with the same figure but in the original G major, abruptly wrenching the movement back to the quartet’s home key. Likewise, the music at the end of the finale leans toward the key of B, but the conclusion once again yanks the key back to G. Thus, the finishing figure has an unsettling role in the final two movements and further underscores how the lyrical simplicity on surface of this quartet can disguise the many layers beneath it.

Dmitri Shostakovich: String Quartet No. 7 (1960)

Now several years after Stalin’s death and the initiation of the post-Stalin Thaw, the mid-1950s to 1960 would see great fluctuations in the cultural policy of the Soviet Union. The strictures instigated in the 1948 condemnation of Shostakovich and others were cited as flawed by some officials, reinforced later as dogma, and relaxed once again. The brutal suppression of the Hungarian uprising in 1956 and Boris Pasternak’s forced refusal of the Nobel Prize for Dr. Zhivago in 1958 are just two examples of the return to hardline policy, albeit tempered by a government no longer willing to engage in mass arrests and executions.

Shostakovich began his Seventh Quartet in the second half of 1959. Divorce from his second wife became official in August, and this quartet, completed in March 1960, was dedicated to the memory of his first wife, Nina Vasilevna Shostakovich. While many have speculated upon the meaning of the dedication and its effect upon the music, most agree the quartet is a remarkably inventive work that signals a significant stylistic change in the composer’s quartet writing.

While the Sixth Quartet represented, at least on its surface, a return to convention in its four-movement structure and lyrical melodies, the Seventh is in three movements like the Fifth, but instead of a balanced distribution, the emphasis here is clearly on the longer, cyclic finale. The melodic and rhythmic consistency between movements in Quartets Four through Six is taken to greater heights in the Seventh as it opens with the solo violin playing, and the lower three voices answering with, a short-short-long (anapest) rhythm so characteristic of Shostakovich.

The light scoring of this first theme gives way to a jaunty second theme in the cello using the same anapest rhythm. The return of both themes in the original key (the first transformed into a pizzicatowaltz) creates a sonata without development, or sonatina form, that is surprisingly straightforward compared to previous opening movements whose sonatas usually restate themes in a compressed fashion. The movement’s coda recalls the first theme.

The second movement, like the first, principally uses the first violin and cello for melody, perhaps insinuating a female and male voice (i.e., the deceased wife and the composer). David Fanning has suggested the light scoring of both movements (i.e., the absence of instruments in many passages) as a possible metaphor for Nina’s absence. In any case, the brief second movement, also with two themes, places the second violin almost exclusively in an accompanimental role. Initially playing arpeggios beneath the first violin melody that alludes to the primary theme of the Fifth Symphony, the second violin changes to a repeated-note, dotted rhythm to compliment the second theme doubled in the viola and cello. For Yale music theorist Patrick McCreless, author of the Shostakovich article in Intimate Voices: The Twentieth-Century String Quartet, Vol. 2, this passage evokes the passacaglia interlude from Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, a work the composer also dedicated to his first wife. The first violin takes over the melody that leads into the coda, beautifully combining the second theme conclusion with the primary theme. The viola now has the arpeggiated accompaniment and adds a four-note descending scale to connect this movement to the finale.

The third movement proceeds from the second without break, and Shostakovich, as he commonly does with such connections, begins the new movement with a transitional passage. This highly dissonant transition combines the short-short-long motive of the opening movement, now ascending, with the viola’s descending scale that concluded the second movement. The viola then launches into a furious fugue whose subject uses the interval pattern of its previous descending scale but now in a much quicker rhythm followed by the dotted rhythms from the second movement’s accompaniment to its second theme. The viola and second violin, who had been relegated to accompanimental or doubling roles, now lead the fugue as the first violin and cello follow with the third and fourth subject entrances. Conventional fugue elements are used to manipulate the fugue’s theme, such as augmentation (doubled rhythmic values) and stretto (overlapping entrances). The climax occurs when the fugue subject disappears and the first theme from the second movement is played in the viola and cello, transformed by the violin accompaniment to a violent character that retains nothing of its original lyrical quality. The music evolves into an equally violent return of the opening movement’s primary theme that slowly dissipates the intensity of the fugue.

The second main section of the finale commences with a waltz-like transformation of the fugue theme extended with new material that will now alternate with staccato and pizzicato restatements of the first movement’s primary theme. The coda from the first movement reappears to conclude the quartet. Although the return of themes from earlier movements in the finale had occurred as early as Shostakovich’s Third Quartet, the degree of integration in this finale is unprecedented. The instability and angst of the finale’s beginning fugue makes it sound more like the development missing in movements one and two. Combined with the work’s overall melodic and rhythmic consistency, this gives the quartet a united, single-movement quality, which is an essential characteristic of many of the quartets that follow.

Dmitri Shostakovich: String Quartet No. 8 (1960)

It is somewhat unfortunate that the artistry of Shostakovich’s Seventh Quartet, a work conceived over eight months, would be immediately overshadowed by that of his Eighth, written in only three days.The circumstances of the Eighth’s composition, its deeply personal voice, and the tragic emotional arc it travels have made this piece the most recognized quartet in the entire cycle.

In July 1960, Shostakovich was scheduled to compose music for Five Days—Five Nights, a movie about the devastation of Dresden during World War II, directed by his good friend Leo Arnshtam. After watching film that recorded Dresden’s destruction and visiting portions of the city still in ruins, the composer traveled to a resort area in Gohrish on the Czech border to begin work on the film score. Instead, he composed the Eighth Quartet. The printed score would bear the subtitle, “To the Victims of Fascism and War.” While this seems an appropriate dedication given the composer’s recent travels, it is unclear who actually wrote the caption. It does not appear on the composer’s autograph score and both his children insist Shostakovich did not write it.

The dedication the composer intended, according to his friend Isaak Glikman, was to himself. “I started thinking that if some day I die, nobody is likely to write a work in memory of me, so I had better write one myself,” was what Glikman recalled Shostakovich saying about the Eighth. Why, at age 54, was the composer thinking of his death? Lev Lebedinsky believed Shostakovich was contemplating suicide due to mounting pressure to join the Communist Party. Although he had taken on many official duties and made public speeches in favor of Soviet policy, the Soviet Union’s most prominent composer had always managed to avoid Party membership. Despite his attempts to evade the request, and with a great degree of self-loathing, the composer eventually relented. His son recalled this as only the second time he saw his father weep openly, the first since the death of his wife Nina, in 1954.

The Eighth Quartet was an extremely personal work for Shostakovich. This is clear from its quotations and allusions to many of his previous works and, especially, the overwhelming presence of his personal musical motif: DSCH. These letters, the first from “Dmitri,” the others from the German spelling of his last name, “Schostakowitsch,” are translated to musical notes as D ‚Äì E-flat ‚Äì C ‚Äì B-natural. In German, the letter “S,” pronounced “Es,” is understood as E-flat, and H indicates B-natural. (“B” in German musical letters is understood as the note B-flat.)

Hinted at in previous works, this motive was first used prominently in the Tenth Symphony, but appears in all five movements of the Eighth Quartet, explicitly identifying the personal touch of the composer and uniting the movements, which are performed without pause.

The DSCH motive opens the first movement in an imitative passage, often mistakenly referred to as a fugue, and is used as punctuation to quotations from his First Symphony and allusions to his Fifth. In the quartet’s violent second movement, it appears in tandem with a quotation of the “Jewish” theme from the finale of his Second Piano Trio. The motive is used as a satirical waltz in the third along with quotations from his First Cello Concerto. The fourth movement is characterized by disturbing fortissimo chords in an anapest rhythm played by the bottom three instruments, offset by a quotation of the revolutionary song “Tormented by Harsh Captivity” and a reference to the pleading aria, “Seryozha, my Darling,” from Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk stated in the cello’s highest register. In this movement, the DSCH motive appears only at the conclusion and leads into the finale. The fifth movement is clearly reminiscent of the quartet’s opening, now using DSCH in a proper fugue that provides closure to a work whose previous four movements were decidedly inconclusive.

What are we to make of this exceptional piece of music? The presence of overt quotations and imagery, as well as the composer’s personal motto, have been extolled by some as a masterfully detailed record of the composer’s oppressed past and criticized by others as limiting the artistic quality of the piece. These debates notwithstanding, this deeply personal, emotionally intense work has firmly established itself in the string quartet repertoire. Perhaps the most accommodating and insightful comment on this piece comes from David Fanning, who, in his extended study of the quartet, states:

At one level it is certainly a powerful reminder of an individual artist’s suffering, and of his compassion. But more than that, it is a reminder of what it is to have a self at all — in a society found on the notion of subordinating the self to the collective, and in an era when the forces of dehumanization were by no means confined to that society.

Nikolai Miaskovsky: String Quartet No. 13 (1950)

While Shostakovich’s life occurred almost entirely within the Soviet era, Nikolai Yakovlevich Miaskovsky (1881‚Äì1950) had lived slightly more than half his years when the Bolshevik Revolution took place. For this reason, he is the only major Soviet composer who was also a member of the pre-Revolution generation of Tchaikovsky and Rimsky-Korsakov; and like them, he made his career not only as a composer, but also as a teacher, scholar, and critic. Miaskovsky came late to formal music study due to his pursuit of a profession as a military engineer. His persistent work and prodigious output would eventually lead him, in 1921, to the position of professor of composition at the Moscow Conservatory, where he would remain until his death.

Miaskovsky’s influence on Soviet music composition would be considerable; among his nearly one hundred students were Khachaturian, Kabalevsky, and Shebalin. Shostakovich almost became a Miaskovsky student when, as a young man, he became frustrated with his teachers in Leningrad and made a formal application to the Moscow Conservatory. Miaskovsky recognized the formal mastery demonstrated by Shostakovich’s submitted compositions and immediately accepted the applicant into his free composition class. But Shostakovich withdrew the application at his mother’s request and remained in Leningrad.

A prolific composer, Miaskovsky wrote over one hundred piano pieces, one hundred twenty-five songs, and a staggering twenty-seven symphonies, a remarkable output for a twentieth century composer. Like Shostakovich, Miaskovsky is primarily known as a symphonist (his Fifth has been designated the “first Soviet symphony”), but he also wrote significantly in chamber music, completing thirteen string quartets.

Along with Shostakovich and Prokofiev (and many other composers), Miaskovsky was among those specifically condemned in the 1948 Soviet decree on “Formalism in Music,” a censure that, in one sense, hurt him more than others because it included several of his students. Unfortunately, he would not live to see his rehabilitation: he died of cancer on August 8, 1950. His Symphony No. 27, written concurrently with the Thirteenth Quartet, would win the Stalin prize posthumously. Shostakovich knew firsthand the terrible effects the decree had on Miaskovsky, having visited him only days before his death. He would recall the older composer saying, “As I lie here, I keep thinking, could it possibly be that everything I did and taught was ‚Äòagainst the People?'” String Quartet No. 13, performed on this recording, is Miaskovsky’s penultimate opus.

Cellist Mstislav Rostropovich described Miaskovsky as “a real Russian intellectual,” while Shostakovich called him the “most noble, modest of men.” Miaskovsky’s early works, particularly the Fifth and Sixth Symphonies, suggest a struggle within the composer: whether to follow the practices of the older Russian school that dominated his education or the progressive direction led by Scriabin that was influencing so many of his classmates. In the end, he would take a position closer to the former and establish himself as a champion of traditional musical integrity. His compositions would become firmly entrenched in the chromatic language of the Romantic era combined with Russian modality. His later works therefore lack the harmonic “innovation” then demanded in the West and is likely the reason the best of them had not been as widely circulated as some of his more adventurous earlier pieces (e.g., Third Piano Sonata, Sixth Symphony). Miaskovsky stated that he found composing on the cutting edge of no personal value. What he insisted on were well-constructed forms, lyrical melodies, and clearly conceived counterpoint.

His Thirteenth Quartet in A minor, Op. 86, is in four movements, all in traditional forms. The quartet begins with a melancholy theme in the cello that is expanded and developed by the first violin. In an unusual twist, the secondary theme is first realized as a fugue in the relative major. Its subject is then expanded to the kind of lyrical conclusion expected for a second theme in a traditional sonata form. The subsequent development and thematic return are also conventional.

The second movement is a study in contrasts, artfully juxtaposing duple and triple meters in the two jaunty opening themes, giving way to a mournfully chromatic middle section followed by an abbreviated restatement of the opening (a feature common to Shostakovich but unusual for Miaskovsky). The Andante third movement, also realized in an ABA form, opens with an exquisite chorale-like passage in A major stated twice before flowing into its divergent middle section in minor mode. Here, the melody is stated in three different keys over an undulating accompaniment before returning to the beginning material, now using the B section’s rolling background. All three initial movements conclude with codas that cleverly combine and condense their movement’s themes.

The finale is teeming with themes in its rondo form, the first theme curiously beginning with a concluding figure that leads to an inconclusive ending. Another theme recurs throughout the movement in a transitional role that connects a broader secondary theme whose duple/triple rhythms recall the second movement. The most striking theme, played boldly with double stops in the violins against a pizzicato accompaniment, occurs at the movement’s center.

It is important to remember that the relatively conservative language of this quartet, while a signature of Miaskovsky’s later style, is also a result of the intense official pressure he received to write more accessible music. (Many of Shostakovich’s works of this time are even more traditional, and some venture into the realm of outright propaganda.) Nonetheless, Miaskovsky’s final quartet is a masterfully written work that amply demonstrates the composer’s dexterity and his belief that adherence to conventional harmonic language need not sacrifice compositional craft.

These notes are indebted to the research of David Fanning, Stanley Krebs, Judith Kuhn, Patrick McCreless, and Sarah Reichardt, and the assistance of Gerard McBurney.

William Hussey is Associate Professor of Music Theory at Roosevelt University’s Chicago College of Performing Arts.

Album Details

Disc 1 Total Time:(57:35)

Disc 2 Total Time: (60:05)

Producer & Engineer Judith Sherman

Assistant Engineer & Digital Editing Bill Maylone

Editing Assistance Jeanne Velonis

Recorded July 24–25 and September 3–5, 2010; January 31, February 1, and May 14–15, 2011, in the Foellinger Great Hall, Krannert Center, University of Illinois at Champaign-Urbana

Microphones Sonodore, Neumann KM 130

Front Cover Design Sue Cottrill

Inside Booklet & Inlay Card Nancy Bieschke

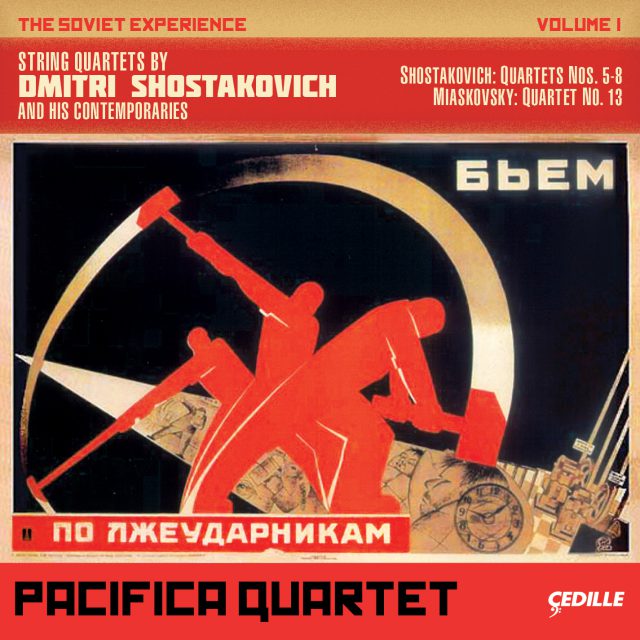

Front Cover Art We Smite the Lazy Worker 1931 Soviet propaganda poster

Our use of this artwork is intended ironically, as a (literally) striking representation of “The Soviet Experience” for composers such as Shostakovich and Miaskovsky, especially at the time of their 5th and 13th Quartets, respectively, coming in the aftermath of the notorious Zhdanov decree of 1948.

© 2011 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 127