Store

Midwestern composer Leo Sowerby’s colorful and evocative symphonic poems, once a mainstay of America’s leading orchestras, can be heard for the first time on CD via a new Cedille Records release, the first in a two-disc series showcasing Sowerby’s symphonic music for a new generation of listeners. (The second in the series is: Leo Sowerby: Symphony No. 2 and Other works)

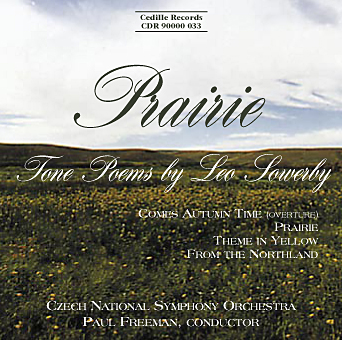

This CD includes the picturesque orchestral suite From the Northland: Impressions of the Lake Superior Country; the lively “program overture” Comes Autumn Time; and two Carl Sandburg-inspired tone poems: the wryly rollicking, Bolero-like Theme in Yellow with its images of Halloween jack-o’-lanterns, and the remarkably vivid and inventive Prairie, the title track, widely considered to be Sowerby’s finest orchestral work.

Headlining the Sowerby series is conductor Paul Freeman of Chicago, a champion of American music and veteran of some 150 recordings for Columbia and other labels. Freeman’s previous Cedille recording was a program of piano concertos by Rudolph Ganz and John La Montaine, composers, who, like Sowerby, have a strong connection to America’s heartland.

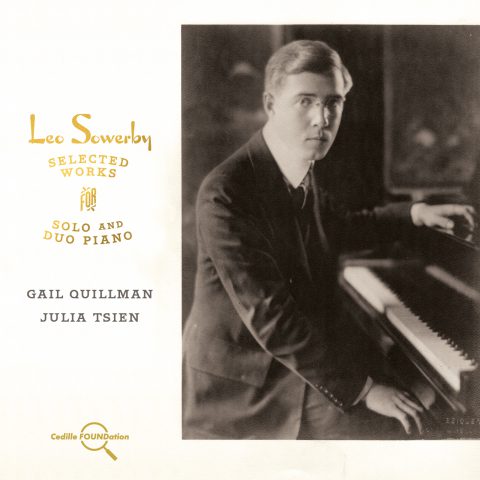

Baker’s Biographical Dictionary of Musicians calls Sowerby a “remarkable American composer . . . eclectic in the positive sense of the word.” Sowerby drew inspiration from American folk music, blues, and jazz, as well as traditional Western concert and sacred music, notes The New Grove Dictionary of American Music. In fact, Sowerby was one of the first serious composers to introduce elements of jazz into the larger musical forms. In 1938, the Musical Quarterly observed, “This 20th century American composes for the present as a part of it, and for the future perhaps even more than he realizes.”

From the Northland: Impressions of Lake Superior Country (1922) was inspired by a motor trip to the Canadian woods around Lakes Superior and Huron.

Autumn was Sowerby’s favorite season, and he was repeatedly attracted to autumnal themes and texts. The overture Comes Autumn Time (1916), although originally written for organ, was the work that launched Sowerby’s career as a major symphonic composer.

Based on a Sandburg poem of the same name, Theme in Yellow (1937) received its premiere performance — and until this world premiere recording, its only performance — on a CBS Radio broadcast from New York, July 31, 1938, with the CBS Symphony conducted by Howard Barlow. Sowerby likely never heard the piece performed: he was overseas during the broadcast and later lost the score and parts. The CD uses a new score prepared by James Winfield of Chicago, who relied on Sowerby’s uncommonly complete pencil sketch and compared it with air-check recordings of the 1938 broadcast.

The disc’s title track, Prairie (1929), was also based on a Sandburg poem. (The poet and composer were mutual admirers.) A 1934 Time magazine profile of Sowerby said the composer asks listeners to “imagine being alone in an Illinois cornfield . . . at peace and one with the beauty that is about.”

Everybody had a taste for Sowerby. The names of Sowerby’s champions reads like a who’s who of 20th-century conductors: Frederick Stock, Serge Koussevitsky, Dmitri Mitropoulos, Pierre Monteux, Howard Hanson, and Eugene Ormandy, to name only a few. Ormandy chose Prairie for his Carnegie Hall debut with the Philadelphia Orchestra. Hanson chose Comes Autumn Time for the first disc of his American music series for RCA in 1939. Sowerby was the most frequently performed American composer on American orchestral concert programs through the 1920s and well into the 1930s, according to the CD’s program notes.

In his heyday, Sowerby was considered positively avant-garde by Midwestern standards. In the following decades, Sowerby, like a whole host of his lyrically inclined contemporaries, saw m

Preview Excerpts

LEO SOWERBY (1895-1968)

Comes Autumn Time

Prairie

Theme in Yellow

From the Northland - Impressions of the Lake Superior Country

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletSymphonic Poems by Leo Sowerby (1895-1968)

Notes by Francis Crociata

In 1927, Carl Sandburg compiled a landmark collection of folk music and published it under the title, “The American Songbag”. Sandburg collected the 306 songs himself, but “for musical settings, for counsel and guidance…technical skill and musical expertise” the poet turned to a consortium of sixteen composers. The largest group of settings came from the newly appointed organist/choirmaster of Chicago’s St. James Episcopal Cathedral and particular favorite of Chicago Symphony conductor Frederick Stock, Leo Sowerby. Sandburg’s “prefatory notes” included this salute:

Leo Sowerby was twenty-one years old when a Chicago orchestra produced a concerto for ‘cello by him entitled “The Irish Washerwoman”. He took a favorite folk piece of American country fiddlers, a famous tune of the pioneers, and made an interesting experiment and a daring adventure with it. He was a band master during the World War. Later he is found doing a happy-go-lucky arrangement for Paul Whiteman’s orchestra; it may be an exploit in “jazz” or possibly a construction in “the new music”. One definite thing about Sowerby is his ownership of himself, his acceptance of hazards. He is as ready for pioneering and originality as the new century of which he is a part. One other definite thing is that he does not prize seclusion to the point where he is out of touch with the People. Not “the peeple” of the politicians, nor the customers of Tin Pan Alley, but rather The Folks, the common human stream that has counted immensely in the history of music. We reckon it a privilege that Sowerby could undertake the musical settings for sixteen of our songs.

Sandburg garbled a few facts, but at that moment in American musical history (and Sowerby’s history as well) he was certainly correct about the “privilege”. The Chicago “orchestra” was actually the Chicago Symphony presenting its 1917 all-Sowerby concert at Orchestra Hall, an unprecedented distinction for an American composer of any age, let alone a 21-year-old. The program included Sowerby’s Cello Concerto and The Irish Washerwoman — two distinct pieces. For Paul Whiteman, Sowerby made no “happy-go-lucky arrangement”: he produced two highly imaginative original works — an overture titled Synconata and a four-movement symphony “for jazz orchestra and 6-1/2 foot metronome” called Monotony (inspired by the Sinclair Lewis novel Babbitt). Thanks largely to another work introduced on the CSO’s “Sowerby Concert”, Sowerby became the most frequently performed American composer in American symphony concert halls through the 1920’s and well into the 1930’s. That piece, the overture Comes Autumn Time, is the one secular work that tenaciously kept Sowerby’s name alive in the symphonic repertory after 1950 when, apart from organ and liturgical works, Sowerby’s music all but disappeared.

The circumstances surrounding the composition of Comes Autumn Time provide one of the most frequently retold Sowerby legends. An early champion of Sowerby’s music was Eric DeLamarter, organist of Chicago’s Fourth Presbyterian Church, as well as a composer, cellist, and conductor. Whenever he was not otherwise professionally engaged, Sowerby had an open appointment as DeLamarter’s assistant and often alternated with his mentor as recitalist for weekly Thursday noon organ programs. On Sunday, October 22, 1916, Sowerby read in the Chicago Tribune that his colleague’s program on the next Thursday would include the premiere of a new work for organ by Leo Sowerby. A telephone call to DeLamarter established that he had intended to request a new work from Sowerby, but had forgotten the detail of actually communicating the request.

Sowerby rose to this accidental short notice “challenge” with one of his most enduring works, composed in a single (Tuesday) afternoon, effectively leaving DeLamarter a single day to learn one of the great tours de force for the organ. Pressed by the program printer, DeLamarter pulled a title out of the air; thus Comes Autumn Time was first introduced as “From the Southland.”

Sowerby didn’t have a title, but he did have an idea or, rather, an inspiration. Autumn was the composer’s favorite season. He was repeatedly attracted to autumnal themes and texts. The aforementioned edition of the Tribune contained verses by the Canadian poet Bliss Carman entitled AUTUMN, and its text was reproduced in the Boston Music Company’s 1919 publication of the orchestral score:

Now when the time of fruit and grain is come,

When apples hang above the orchard wall,

And from a tangle by the roadside stream

A scent of wild grapes fills the racy air,

Comes Autumn with her sunburnt caravan,

Like a long Gipsy train with trappings gay

And tattered colors of the Orient,

Moving slow-footed through the creamy hills.

The woods of Wilton at her coming, wear

Tints of Bokhara and of Samarcand;

The maples glow with their Pompeian red,

The hickories with burnt Etruscan gold;

And while the crickets fife along her march,

Behind her banners burns the crimson sun.

DeLamarter struggled with the organ score. The audience, however, loved it, responding so enthusiastically that DeLamarter asked Sowerby to orchestrate the work for the all-Sowerby program DeLamarter would conduct the following January. It was the most memorable work on that program as well. Chicago Symphony maestro Frederick Stock was so impressed that he immediately commissioned a new piece, the first of a dozen Sowerby works Stock would introduce over the next quarter century. (The German-born maestro even requested that Comes Autumn Time be played at his funeral, on a program otherwise comprising the German masters Bach, Beethoven, and Wagner!)

Stock was not alone in his admiration of Comes Autumn Time and its creator. With its 1919 publication, Sowerby was launched. It was led in Boston by Pierre Monteux, Philadelphia by Stokowski, Minneapolis by Ganz, New York by Damrosch, London by Harty and Wood, Berlin by Rosbaud, and Vienna by Bruno Walter. Stock had already led four more Sowerby premieres and had announced Sowerby’s First Symphony for the 1922 season, but the composer would not be in Chicago to hear it. He was in Rome as the first American Prix de Rome Fellow in music. Sowerby did not compete for the “Rome Prize”, he was simply offered it based on his reputation. He served his Fellowship (1922-24) together with his lifelong friend and fellow-Midwesterner Howard Hanson, winner of the first Prix de Rome competition.

Though identifying himself first as a composer, Howard Hanson had career aspirations as a conductor as well. Returning from Rome to head the Eastman School of Music, he founded an annual Festival of American Music that ran for 49 seasons and featured Sowerby prominently. When he contracted with RCA in 1939 to record a series of American works, Comes Autumn Time comprised disc one of the very first “album” (actually a set of six 78’s).

On May 24, 1924, Hanson organized a concert at the American Academy in Rome, leading the Orchestra of the Augusteo in Sowerby’s orchestral suite From the Northland: Impressions of the Lake Superior Country. It was the third of fourteen major works Sowerby would compose during his three-year Rome Fellowship; like Comes Autumn Time, it began life as a keyboard work: a five-movement piece for piano. From the Northland was inspired by a motor trip Sowerby made in 1919 to the Canadian woods around Lakes Superior and Huron. Sowerby presumably gave the first performance of the piano score at the Academy shortly after completing it on June 16, 1922. At that time, Sowerby was still identified more as a pianist than an organist. He introduced From the Northland to American audiences at his New York debut piano recital at Chickering Hall on October 22, 1924. Fritz Reiner gave the American premiere of the orchestral version on March 20, 1925 with the Cincinnati Symphony.

Sowerby made the orchestration (omitting the third movement, “The Lonely Fiddle Maker”) — at Hanson’s suggestion — on a holiday trip to the Italian region of Trento in July 1923. The manuscript includes Sowerby’s descriptions of the experiences and sights that inspired From the Northland. These were reproduced in the published scores:

I. “Forest Voices.” In the depth of the green dark forest I hear not a sound, save the faint magic murmur of the great trees, which seem to chant a song, hushed and mysterious, which betimes surges and swells, and lapses again into primeval silence.

II. “Cascades.” The sparkling rivulet laughs its way over stones and pebbles, grinds through rapids, and dashes over a great rock in a cloud of scintillating foam. I should like to listen forever to this happy stream, though when I leave it to its play, it bids me no farewell, but runs carelessly on and on its way, caring not for me nor heeding me.

III. “Burnt Rock Pool.” In this pool — who knows how deep — there reigns a silence absolute, a tranquillity sweet and wonderful. I reflect on life, and wonder if this is not the great joy, the highest happiness, to be one with nature’s self.

IV. “The Shining Big-Sea Water.” The blinding light of the summer sun beats down upon the ever-restless Great Lake. The waves hurl themselves with a monotonous never-ceasing rhythm upon the rocky wall of the shore. O my lake! in your every mood, pensive or fearful, you, of all nature, tell me most of joy, of youth, of power, of infinity!

On August 11, 1929, Sowerby made one of his relatively rare appearances as an orchestral conductor. He led the National High School Orchestra in the world premiere of his symphonic poem Prairie, inspired by lines and images from a 1919 poem of the same name by Carl Sandburg, from his collection Cornhuskers. Howard Hanson was present and immediately offered to engrave and publish the work under the Eastman School’s imprint. The published score bears these lines from the poem:

Have you seen a red sunset drip over one of my cornfields, the shore of night stars, the wave lines of dawn up a wheat valley?

Have you heard my threshing crews yelling in the chaff of a strawpile and the running wheat of the wagonboards, my cornhuskers, my harvest hands hauling crops, singing dreams of women, worlds, horizons?

Hanson gave the first major orchestra performance on March 11, 1931 with the Detroit Symphony. Several Sowerby orchestral works after Comes Autumn Time achieved wide circulation, including From the Northland, A Set of Four — Ironics for Orchestra, and Medieval Poem, but Prairie was the only piece that modeled the success of Comes Autumn Time. Hanson played it at Eastman, as did Stock in Chicago. In 1933, Sowerby conducted Prairie with the Cleveland Orchestra. Serge Koussevitsky first conducted Sowerby in Boston in 1931 (Comes Autumn Time) but it was his 1932 performance of Prairie that made Koussevitsky a Sowerby champion almost to rival Frederick Stock. In 1934, Eugene Ormandy, still leader of the Minneapolis Symphony, made his Carnegie Hall debut with the Philadelphia Orchestra, offering the New York premiere of Prairie. This occasioned a Time Magazine profile of Sowerby that liberally quoted from the composer’s own program annotations:

The symphonic poem Prairie is constructed in such a way that sections seeking to interpret the moods of the poet’s “red sunset”, “shore of night stars”, “wave lines of dawn”, “threshing crews yelling in the chaff of a strawpile”, follow one another in succession without break or special line of demarcation. At the end, the composer has sought to recall the mood of the beginning which suggests the hush and perhaps monotony of vast stretches of farm and whose beauty mid-westerners too seldom appreciate, and which Mr. Sandburg has idealized in so American a way in his poem. The composer prefers to make no detailed analysis of the purely musical contents of the score, as he feels this scarcely right or necessary in the case of a symphonic “poem”, though he desires to make clear that he has not wished to write “program music”, he asks only of the listener to imagine being alone in an Illinois cornfield, far enough away from railways, motor cars, telephones, and radios to feel at peace and one with the beauty that is about. If the situation has something of the “homely” about it, so much the better…

Sowerby shifted emphasis in the 1930s toward symphonies, concertos, and the classic forms of the chaconne, fugue, and, especially, the passacaglia. But he did return to the free tone poem fitting his description of Prairie to fulfill a commission for the CBS Radio Network’s 1938 series “Everybody’s Music”. For twenty-six weeks, CBS presented new works by as many composers. Sowerby produced one of his most amazing and virtuosic compositions, fully titled “Piece after Carl Sandburg’s THEME IN YELLOW”. Sandburg gladly gave permission for Sowerby to quote his poem, originally published in Chicago Poems in 1916:

I spot the hills

With yellow balls in autumn.

I light the prairie cornfields

Orange and tawny gold clusters

And I am called pumpkins.

On the last of October

When dusk is fallen

Children join hands

And circle round me

Singing ghost songs

And love to the harvest moon;

I am a jack-o’-lantern

With terrible teeth

And the children know

I am fooling.

Unlike Comes Autumn Time, From the Northland, and Prairie, Theme in Yellow did not open doors or circulate in any form except for “bootleg” copies of discs of the rehearsal of its first — and until this recording, only — performance. That one performance was a studio broadcast on Sunday afternoon, July 31, 1938 with the “CBS Symphony” conducted by the network’s house conductor, Howard Barlow. There was no audience and, unless Barlow arranged for the composer to hear air check discs, Sowerby probably never heard Theme in Yellow. (The composer was at the Venice Festival to hear Dmitri Mitropoulos conduct his Second Piano Concerto.) The CBS players reveled in the interlocking succession of jazz-inspired riffs and flourishes (especially their young oboist — one Mitchell Miller!).

When near the end of his life, Sowerby was asked by Chicago Symphony conductor Jean Martinon for a list of his “favorite” works with the intention of restoring Sowerby to the CSO’s repertory, the composer named his five symphonies, Prairie, and Theme in Yellow. Answering a similar request from Fritz Reiner, Martinon’s predecessor, the composer had also offered Theme in Yellow, but was then unable to locate the score and parts. (Reiner opted for Passacaglia, Interlude and Fugue. Martinon left the Chicago podium before he could follow through.)

Score and parts to Theme in Yellow are still lost. This recorded performance uses a new score prepared by James Winfield of Chicago with a grant provided by friends of the Leo Sowerby Foundation. Winfield used Sowerby’s uncommonly complet pencil sketch, checking it against air check recordings of the 1938 performance.

Francis Crociata is President of the Leo Sowerby Foundation.

Album Details

Total Time: 62:35

Recorded: October 21-24, 1996 at the studios of Czech National Radio in Prague

Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineer: Bill Maylone

Production Assistant: Francis Crociata

Cover Photograph: Chief Joseph s Bear Paw Field, Blaine County, Montana (detail) © Gus Foster Design: Cheryl A Boncuore

Notes: Francis Crociata

© 1997 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 033