Store

There’s a joke about a tourist in New York who asks a passerby how to get to Carnegie Hall. “Practice, practice, practice,” he’s told. During the 1970s and ’80s, the answer could also have been, “Emigrate from Russia.” With numbing regularity, another Russian emigre “sensation” would fly into New York on the wings of hope, only to fall off the cultural radar soon after.

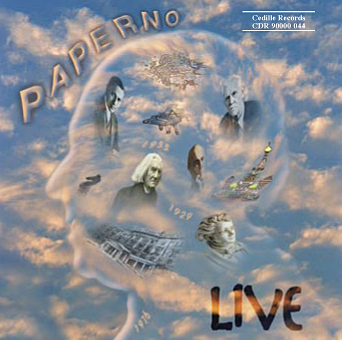

Few of these ballyhooed Soviet defectors arrived with the talent or credentials of Dmitry Paperno, an unpresuming pianist who celebrated his seventieth birthday in 1999 in his adopted hometown of Chicago. Culled from Paperno’s live broadcasts for Chicago fine arts station WFMT-FM from 1980 to 1991, this CD pays tribute to Paperno, his sixth for the independent Chicago label.

Preview Excerpts

FRANZ JOSEPH HAYDN (1732-1809)

Sonata No. 20 in C minor

FRANZ SCHUBERT (1797-1828) / tr. Liszt

ROBERT SCHUMANN (1810-1856) / tr. Liszt

FRANZ LISZT (1811-1886)

ROBERT SCHUMANN

Bunte Blatter Op. 99, Nos. 1-8

JOHANNES BRAHMS (1833-1897)

PIOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY (1840-1893)

SERGEI RACHMANINOV (1873-1943)

NIKOLAI MEDTNER (1880-1951)

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletDmitry Paperno Live

Notes by Raymond Tipper

Franz Joseph Haydn (1732-1809) wrote the Sonata No. 20 in C minor (Hob. XVI: 20) in 1771 at the court of Prince Nikolaus Esterházy, where Haydn worked as musical director for almost three decades. Even for a work in a minor key (rare for Haydn) the mood is unusually sad — sometimes almost dark — for the typically jovial “Papa” Haydn. There is even a suggestion of drama and protest in the Finale: several stops and restarts are used, not humorously, as with Haydn’s “big” E-flat Major Sonata (No. 52), but to indicate uncertainty or anxiety. (Haydn used this technique in at least one other melancholic piano sonata (No. 32, 1776), written in the key of B minor — especially rare for the classical period — and also in his Andante and Variations in F minor, and the “Farewell” Symphony No. 45 in F-sharp minor.) While one always hesitates to assign extra-musical associations to non-programmatic works, it seems more than a coincidence that Haydn would write such a forlorn-sounding work at a particularly troubled time in his life: He had recently learned of an affair between his wife and a painter Esterházy hired to produce a family portrait.

Franz Liszt (1811-86) transcribed for solo piano more than fifty Schubert songs. Both of the works here, Gretchen am Spinnrade and the Barcarolle, Auf dem Wasser zu singen, come from a collection of twelve Schubert transcriptions Liszt published in 1838. The Barcarolle offers the better example of Liszt’s amazing creativity as a transcriber. Here Liszt turns the verses of a simple strophic song into a set of variations by shifting the voicing of the melody: from the tenor voice (second from bottom) in the first verse, to alto in the second, to soprano in the third. The final verse expresses the melody chordally, above the stormy, undulating accompaniment, converting the prevailingly sad feeling of Schubert’s song into an exclamation of the jubilation of love. While Schubert shifts into the major key at the end of each verse, Liszt adds to the final excitement by intensifying the texture and boosting the dynamics to fff at the end.

Liszt’s transcription of Gretchen at the Spinning Wheel (from Goethe’s Faust) is more of a “straight” transfer, except for one ingenious departure from the original song: Because Gretchen’s vocal line often collides with the swirling accompaniment depicting the turning of the wheel, Liszt places such coincidental notes in the “vocal” part a sixteenth note later to preserve the melody. Impressively, Liszt’s transcription manages to convey all the passion of one of Schubert’s earliest and most dramatic songs. Note, for example, how Liszt preserves, almost verbatim, Gretchen’s fervent reminiscence of her first kiss when the spinning wheel suddenly stops, followed by a long pause and the wheel’s gradual return to its monotonous rotation.

Frühlingsnacht (Spring Night), from Schumann’s 1840 collection of twelve songs, Op. 39, is one of only four Schumann songs Liszt transcribed for piano, only two of which are still in the concert repertoire (Widmung is the other). Liszt’s transcription, which he published in 1872, reproduces the restless, vibrating accompaniment of the original song, which expresses the beauty of a misty, moonlit spring night with twinkling stars and rustling leaves. As with the transcription of Schubert’s Barcarolle, the hymn-like jubilation at the end of this piece derives from the original, but Liszt’s bright textural and dynamic treatment makes it sound even more joyous.

Sposalizio (Betrothal), composed in 1839, is the first piece from Liszt’s Années de Pèlerinage Book II (Italy). Liszt modeled Sposalizio after a 1504 painting by Raphael depicting the exchange of rings between Mary and Joseph. The piece opens with a pensive, descending melodic line followed by a three note “question.” Liszt gradually develops this indivisible design into a triumphant climax with bells tolling (signaling what, or rather Who, is to come . . .). Shimmering descending eighth notes, like a curtain slowly falling on the blessed scene, lead to a quiet ending of utmost calm and serenity.

The set of fourteen pieces Robert Schumann (1810-56) titled Bunte Blätter (Many-Colored Leaves), Op. 99, contains many relatively early works (despite its late opus number). The collection comes in three sections: Drei Stücklein (Three Pieces), composed in 1839; Albumblätter, five pieces composed 1836-41; and six individual pieces composed 1838-49. The eight miniatures performed here, which comprise the two grouped sets, are from the same period as Schumann’s finest piano cycles, including Fantasiestücke, Op.12 (1837) and Humoresque, Op. 20 (1838). Schumann had even originally planned the sixth piece (A-flat major) in Op. 99 for Carnaval, Op. 9. Like Medtner’s “Forgotten Motives” (Op. 38-40), and Prokofiev’s “From Old Notebooks” Sonatas (Nos. 3 and 4), Bunte Blätter shows a composer turning for inspiration to earlier themes and pieces, with especially fortunate results. The first piece in Op. 99 is one of Schumann’s melodic masterpieces. The second offers a beautiful example of polyrhythmic ingenuity: In each measure, Schumann incorporates simultaneously eighth-note triplets in the upper voice, thirty-second notes in the middle, and delayed quarters in the bass. Nos. 5 and 6 are closely associated with Brahms, who wrote a set of piano variations on No. 5, and used the texture of No. 6 in one of the variations.

In 1892, toward the end of his life, Johannes Brahms (1833-97) wrote four sets of piano pieces: the seven Fantasies, Op. 116; three Intermezzos, Op. 117; six Pieces, Op. 118; and four Pieces, Op. 119. While harmonically identical to Brahms’s earlier works, these later pieces display a simplicity and economy of expression that is clearly the music of a mature genius. Even among these late sets, a distinction can be made between Op. 116, with its three stormy Capriccios, and the last three groups, which are even more philosophical and pessimistic in their outlook.

Even for the gloomy Op. 117 set, the C-sharp minor intermezzo is especially dark. The work’s message seems intensely personal, as though the composer was already preparing to say “farewell” to the world. The listener is immediately struck by the slow pace of its sadness as the desolate melody is constantly expressed through “empty” octaves. The major key middle section is racked with bittersweet reminiscences, and the return of the “A” section is even sadder than the beginning. All these features and others — the inevitably descending cadences; the prevalence of very narrow intervals, primarily seconds — create a feeling of departure and despair, but with a dignity that makes the feeling even stronger. There is a flash of hope in the recapitulation, when the music makes a passionate attempt to stay in B major a little longer than in the exposition, only to fail bitterly one bar later. Other than this brief moment, there is not a shade of protest or complaint, as though Brahms were saying that, no matter how hopeless, one must accept one’s fate.

Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-93) wrote the Dumka, Op. 59 in 1886. (A Dumka is a type of Slavic folk song.) The work occupies a unique place in Tchaikovsky’s output as the only single-movement solo piano piece Tchaikovsky published separately (i.e., not as part of a larger collection). It is the most virtuosic or “Lisztian” of Tchaikovsky’s piano works. A Russian rhapsody analogous to Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsodies, the Dumka begins with a simple, melancholic melody and then travels through a series of increasingly animated episodes — first dance-like, then becoming more fervently emotional and tragic. Tchaikovsky’s “rhapsody” does not end triumphantly as Liszt’s do. The Russian composer concludes by returning to the melody that opens the piece, now in a lower register — an ending that feels even more melancholy because of the jubilation that precedes it.

Sergei Rachmaninov (1873-1943) wrote his six Moments musicaux, Op. 16, dedicated to the amateur pianist Alexandre Zatayevich, in 1896, at the age of 23. The fifth of these, marked Adagio sostenuto, is an example of the utmost beauty, dignity, and lyricism. It is not at all sentimental, yet touches the heart in the most profound way, bringing a sense of peace, balance, and contentment to the listener. Especially magical are the angelic echoes of the melody that Rachmaninov adds in the upper register at the end. A piece of such simplicity and wisdom, it is an extraordinary achievement for such a young composer.

Nikolai Medtner (1880-1951) composed his three-volume cycle of “Forgotten Motives,” Op. 38-40, in the winter of 1919-20. During this devastating post-revolutionary period, Medtner lived outside of Moscow in a house with no electricity or running water, and an out-of-tune piano. The title “Forgotten Motives” refers to themes and fragments from old sketchbooks (c. 1916). The longest and most ambitious piece in Op. 38 is the single-movement Sonata Reminiscenza, which opens the cycle. Its combination of romantic lyricism — sometimes almost improvisatory — with strong classical architecture makes this one of the most Beethovenesque of Medtner’s works. (Medtner was a great admirer and interpreter of Beethoven.) It is also a stellar example of motive work within the sonata form, and of Medtner’s unique polyphony, which permeates the piece.

Unlike Beethoven, however, whose stormier sonatas usually present conflicts from the outset, Medtner’s exposition offers little hint of the struggles to come: It opens with a disarmingly simple statement of the melancholic theme on which all eight of the Op. 38 pieces are based and never strays far from that theme, concluding with a restatement (in E minor instead of the original A minor). The composer balances this placid exposition with an extremely dramatic and turbulent development, which explodes onto the scene with a veritable thunder-clap. Medtner takes the listener on an amazingly wide-ranging harmonic and emotional journey throughout the development and recapitulation. Yet even the most adventuresome passages remain saturated with thematic material from the exposition. After this wild ride, Medtner frames the piece with a beautiful recurrence of the bittersweet opening melody.

Album Details

Total Time: 77:17

Recorded:

Tracks 7 & 17 recorded at DePaul Concert Hall, May 15, 1980.

All other tracks were recorded in WFMTs Studio One:

Tracks 1-3, & 19 on November 22, 1983;

Tracks 4 & 5 on March 22, 1987;

Tracks 6, & 8-15 on September 21, 1986;

Track 16 on November 3, 1991;

and Track 18 on August 7, 1995 during a special recording session to replace the original performance (May 15, 1980)

Producer: James Ginsburg

Cover Photo & Design: Nesha & Kumiko Fotodesign

Booklet Design: Cheryl A Boncuore

Notes: Raymond Tipper

© 1999 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 044