Store

Store

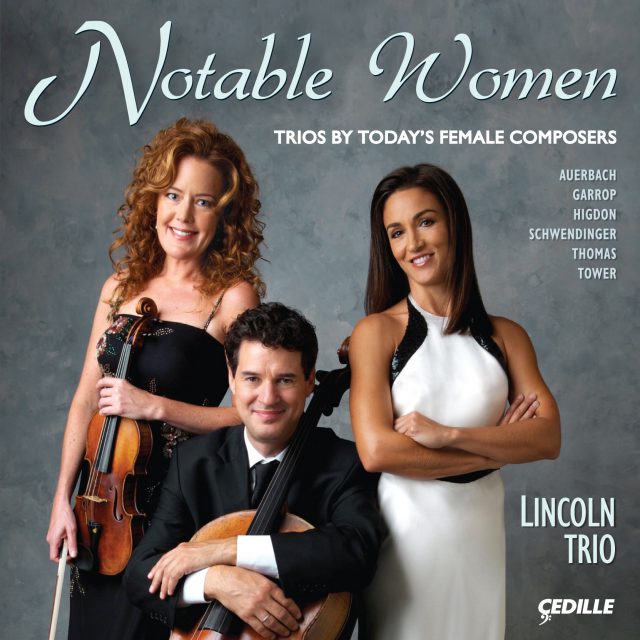

Notable Women: Trios by Today’s Female Composers

Stacy Garrop, Lera Auerbach, Augusta Read Thomas, Marta Aznavoorian, Desirée Ruhstrat, David Cunliffe, Jennifer Higdon

This imaginative program, devised by the dynamic Lincoln Trio, features works by six celebrated contemporary American female composers. Four of the pieces are world-premiere recordings: Lera Auerbach’s Trio, Stacy Garrop’s Seven, Laura Elise Schwendinger’s C’è la Luna Questa Sera?, and Joan Tower’s Trio Cavany. Writing for ChicagoClassicalReview.com, former Chicago Sun-Times critic Wynne Delacoma called the program (played live at a 2010 concert), “an afternoon of bracing, highly varied music written by some of contemporary music’s most talented composers — male or female” offering “a window to what’s happening on the contemporary music scene.”

Preview Excerpts

LERA AUERBACH

Trio for violin, cello, and piano

STACY GARROP

JENNIFER HIGDON

Piano Trio

LAURA ELISE SCHWENDINGER

AUGUSTA READ THOMAS

JOAN TOWER

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletNotes by the composers and Andrea Lamoreaux

Notes by Andrea Lamoreaux

A popular form of home music-making in 18th-century Vienna, trios for piano, violin, and cello were transformed into concert music during the 19th and 20th centuries but still retain their sense of intimacy and personal conversation. The six trios on this CD, all by living American women composers, reflect the genre’s twofold advantage of providing an opportunity for ensemble playing — from emphatic unison passages to flowing contrapuntal sections — plus the chance for each player to shine in a solo role.

Moon Jig (2005)

Notes by Augusta Read Thomas

Traditionally, a Jig (or Gigue) has been a lively dance with leaping movements, comprised of two sections each repeated. Somewhat of a cross between jazz — Monk, Coltrane, Tatum, Miles, etc. — and classical — Bartók, Brahms, Stravinsky, etc. — Moon Jig can be heard as a series of outgrowths and variations, which are organic and, at every level, concerned with transformations and connections. The piano serves as the protagonist, as well as fulcrum point on and around which all musical force-fields rotate, bloom, and proliferate. The piano part starts with (and returns four times with) a low-register jig, which is an earthy, punchy, rhythmic, asymmetrical walking bass. The second, contrasting section (which is also repeated four times) is always led by the strings, which play long, animated, expressive lines. This very short work alternates five times total between these two sections: piano-jig, tutti, piano-jig, tutti, piano-jig and so forth, yet as the repetitions proceed, the two musics eventually blend together. One clear-cut example is when the string pizzicatos blend into the low-register, jazzy piano rhythms. A multi-faceted merging process finally results in one long sweep of music rushing to the end in the highest registers of the trio, as if the Jig leaped skyward and moonward. Moon Jig, commissioned by the Music Institute of Chicago, was premiered by the Lincoln Trio on May 5, 2005, at the Four Seasons Hotel in Chicago at a private party.

Thomas’s moon metaphor is strikingly different from Schwendinger’s: the moon here seems a spectacular goal to be reached via rhythmic intensity, rather than Schwendinger’s source of evocative, ambient light. The piano’s first iteration of its jazzy walking bass is marked to sound like “Funky, asymmetrical, sporadic jabs.” The composer uses the indication Rubato right at the beginning to indicate rhythmic freedom. With the strings’ first entry we hear the cello’s insistent repeated notes in a high register, underpinning the violin’s exuberant, improvisatory motive. From this point on, the entrances and exits of the three instruments are abrupt and unexpected, with sudden accents, quick dynamic changes, emphatic chords, and rapid shifts between pizzicato (plucked) and arco (bowed) figures in both string parts. The violin’s opening figure returns to punctuate the work’s progress toward a rapidly-accelerating fortissimo conclusion.

Piano Trio

Notes by Jennifer Higdon

(2003; dedicated to Joan Tower; commissioned by the Bravo-Vail Music Festival)

Can music reflect colors and can colors be reflected in music? I have always been fascinated with the connection between painting and music. In my composing, I often picture colors as if I were spreading them on a canvas, except I do so with melodies, harmonies, and through the instruments themselves. The colors that I have chosen in both of the movement titles and in the music itself, reflect very different moods and energy levels, which I find fascinating, as it begs the question, can colors actually convey a mood?

The first movement, a moderate Andante, is subtitled Pale Yellow. Listening to it, other colors might come to mind, but they would all be pastels. If the movement were a work of visual art, it would definitely be a representational painting. The opening key is a radiant A major, with flowing themes presented in traditional diatonic harmonies in which triads and the interval of a major sixth are emphasized. The three instruments play mostly together, with brief soloistic interludes or passages of imitation. There is no transition to the minor mode. The movement intensifies with increasing sixteenth-note patterns and dotted rhythms until a sudden key change, with similar motives to the opening, arrives in another serene-sounding key, B-flat major. This transition from a key of three sharps to one of two flats imparts a subtle, almost indefinable change to the sound. A quiet, sustained ending gives a hint of what is to come, as a B-flat chord is enriched with intervals of a major seventh and a major second: just a slight touch of dissonance.

Fiery Red is the name for the blazingly fast second movement. Here the color is quite definite: the music is indeed fiery. Beginning with abrupt sixteenth-note patterns, huge string chords, and octaves in the bass of the piano, the movement soon turns to brilliant up-and-down runs for the strings, complemented by a fast-moving, dissonant piano part accentuated by glissandos. The dynamic is loud, with sudden softer contrasts; the strings are asked to play “sul ponticello” and to use harmonics. Then as the piano part becomes less insistent, a brief interlude emerges with ostinatos — repeated notes and double-stops — for violin and keyboard. These ostinato passages are interspersed with sixteenth-note passages reminiscent of the movement’s opening. After some measures in which all three instruments play in high registers, there comes a recapitulation of sorts with the return of the up-and-down runs while, rondo-like, the ostinato pattern returns in its midst. At the end, the piano plays increasingly powerful chords until all is suddenly resolved on an A major chord.

Trio Cavany (2007)

Notes by Joan Tower

Trio Cavany was commissioned by La Jolla Music Festival, the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, and the Virginia Arts Festival. It is dedicated to violinist Cho-Liang Lin, who gave the premiere in the summer of 2007 at the La Jolla festival with cellist Gary Hoffman and pianist Andre-Michel Schub. The title covers the three states the festivals are in. [The trio] is in one movement . . . and features all three instruments in solo and in combination.

Trio Cavany emphasizes the solo potential of each instrument within a piano trio, bringing them together into a unified whole, but with constant solo statements along the way. It begins with a pianissimo violin statement of the basic three-note motive that will constantly recur, in various registers and rhythms, to unify the work: it drops down one step, then rises by a minor third. The cello also enters very high-pitched, and the two strings play in tandem for a while, imitating and echoing each other, until they drop out in favor of an extended, dramatic, and virtuosic piano solo. The cello then presents a melody derived from the three-note motive and is soon rejoined by the violin. Another lengthy piano passage is accompanied by sustained, muted notes from the violin and cello, then rhythmic interest is emphasized in a section of two-against-three patterns. Double-stops and sixteenth notes become prominent in the string parts as we lead up to a “drammatico” cello solo followed by another piano statement.

The violin gets its solo chance with a virtuosic passage that ends with a restatement of the three-note motive. This is followed by a new section, analogous to a slow movement, launched in a mellow 6/4 time. There’s a sense of distance here, with another high-register cello part and pianissimo chords in the piano. The section grows in dynamic intensity toward reiterated fortissimo piano octaves. The three-note motive, in cello, then in violin, takes us to a brief piano solo statement, where the pace momentarily slows down as the composer indicates, “broaden.”

With violin and cello soon rejoining the piano, we’re led onward to a final section, announced by repeated dotted rhythms that become insistent ostinatos for all three players. These quickly become powerful fortissimo octaves, first in the piano, then in all three parts, with a return to the two-against-three rhythms. The violin reaches a high point that is almost a scream. Syncopated patterns and rapid imitations, another brief piano solo, and a sudden unison passage bring us to the final measures, with strong, dissonant chords and a final fortissimo accent.

C'è la Luna Questa Sera?

Notes by Laura Elise Schwendinger

(1998/2006; in memory of Donald Martino)

C’è la Luna Questa Sera? [Is There a Moon Tonight?] was inspired by the moonlight reflected on the surface of Lake Como. After spending a lovely and productive month at the Bellagio Rockefeller Center in 1997, my memories of the evenings there revolve around standing out on the veranda and watching the moonlight dance off the water. Surrounded by the dramatic views of the Dolomite Mountains to the east, and the Alps to the north, the setting was magical, yet mysteriously enigmatic at night, as the purple hue of the Dolomites gave the surrounding visual frame a dark aura of ambiguity. The other side of the Dolomite Mountains was visible only when there was a full moon, and even then the color lent an almost ethereal ambience to the scene. The work was originally for violin, cello and percussion and was transcribed specifically for the Lincoln Trio, to which this version is dedicated.

The piece unfolds in one continuous and rhapsodic movement. The violin and cello are often placed in extremely high registers and sustained over multiple measures. When the violin is not sustaining high notes, it frequently plays in octave-separated unisons with the cello, with the same “bell-like” material heard in the opening piano part. The thematic patterns that emerge are characterized by augmented intervals: fourths (tritones), fifths, and sixths, with the rhythmic patterns becoming more intricate. Slowly a motivic figure emerges, characterized by a three-fast-note-turn figure leading to a sustained one. Beginning with a strongly accented note, the piece immediately drops to a quiet dynamic level then gradually increases toward a midpoint. A long unison melody, very lyrical, very moonlit, is presented mezzo-piano by violin and cello, with rapid piano figuration to provide an undercurrent of a new momentum. This momentum leads to a very high-register cello solo, and to the return of stratospheric notes in the violin part. Toward the end, the cello restates the motive with the three- fast-note-turn figure, over which the violin plays an extended tremolo. The piano part ends after some emphatic forte notes, and underneath the violin’s high song, the cello gets the final word.

Trio for Violin, Cello and Piano(1992/1996)

Notes by Lera Auerbach

In 1991, at the age of 17, during a concert tour in America, six months before the fall of the Soviet Union, I decided to defect. The following year, 1992, when the first two movements of this trio were written, was perhaps the most difficult of my life. I was alone, and did not know whether I would ever see my family again. Many of the works of that period were not completed until a few years later; this trio is one of them. The last movement, Presto, was written four years later, in 1996. The first movement is marked Preludium Misterioso. Its melodic line is angular with steady rhythm, interrupted by accents and syncopations, and the writing is polyphonic in nature. The second movement, Andante, is the emotional center of the work. It is a lyrical and tragic dialogue between violin and cello, with piano providing a sustained harmonic pedal. In this trio the whole structure is built as one continuous crescendo towards the end. Crescendo is not meant in the dynamic sense, but rather as a buildup of the gravity of the material: the first movement is a short Scherzo, the second an emotionally-charged Andante, and the third, Presto, a toccata with its climatic modulation to C major. The last movement requires virtuosity in all instruments. The main material of the third movement is characterized by its obsessive quality, while its middle section is contrastingly still and dead. The main themes of the first and second movement are incorporated and intertwined with the material of the toccata. In the climax of the third movement, all the main themes of the trio become one.

The Prelude begins with that angular theme in the piano, taken up by the cello and then the violin (starting it a fifth higher). There are indications for violin and cello to play “sul ponticello,” meaning the bow is near the instrument’s bridge, producing a dry and detached sonority; the piano part is sometimes marked staccato and “secco” (dry). As the Prelude moves toward its peaceful C major close, the cello plays eerie glissandos, passages where the fingers slide rapidly up and down the strings. The score says: “Imitating the cries of seagulls.”

The Andante gives the piano a slowed-down variant of the Prelude’s main theme, supporting a lyrical, melancholy cello solo: there’s a momentary bluesy sound before the violin enters with a soaring, highly chromatic melody that proceeds in counterpoint with the cello’s material. A brief piano solo takes up the cello’s theme and decorates it with a “glass-like sound.” As the movement builds up intensity, the violin is asked to play “flautando” (literally, “flute-like”): the bow is drawn across the strings near the fingerboard, producing yet another unusual sound. The Andante dies away to a quiet ending in C.

The Presto is a marked contrast of both mood and texture: agitated and rapidly-paced, it features emphatic piano chords and octaves, flying 16th-note passages, and double- and triple-stops for the strings. The sense of headlong perpetual motion is enhanced by frequent dynamic markings of fortissimo, contrasted by sudden indications to play softly. The relatively lean sounds of “sul ponticello” and “flautando” appear again. The brief “still and dead” midsection is marked Misterioso to recall the first movement. Heavy chords and string tremolos over a pounding piano lead to a triple-forte final C.

Seven

Notes by Stacy Garrop

(1997-98; in memory of my father, Norman Garrop)

The genesis of Seven emerged from two separate sources. The first is Anne Sexton’s evocative poem ”Seven Times” in which the speaker longs for release from life. Upon dying, she is surprised to find a quiet, peaceful place:

I died seven times

in seven ways…The second source was the TV show Star Trek Voyager. One of humanity’s worst enemies are the Borg, which are a half-machine, half-organic species who assimilate all species they encounter and add them to their collective consciousness. The crew of Voyager managed to sever one Borg’s connection with the collective, thus leaving the Borg isolated and human for the first time since she had been abducted as a young girl. This Borg, named Seven of Nine, found the isolation of being an individual almost unbearable for numerous episodes before she began realizing her full potential in her new human life. As I began writing the trio, I saw a connection between Sexton’s poem and Seven of Nine. Both represent change. Anne Sexton’s speaker craves death. Seven of Nine fought her forced change from collective consciousness to isolated individualism. Neither character expected what waited for them on the other side. This change is represented musically near the end of the piece. You might imagine the change to be Sexton’s moment of death, or of Seven’s switch from Borg drone to human.

Seven, in seven interlinked sections with frequent tempo contrasts, features several sonic special effects, with particular demands on the pianist. She must hit the instrument’s strings with the palm of her hand, physically mute some of the strings, hit numerous keys at once, play with the forearm, and then quickly shift back to playing normally, while using the sustaining pedal for sudden punctuations. The string players are asked to play with and without mutes, to play “sul ponticello” and “col legno” — with the wooden part of the bow. They also play frequent tremolos and glissandos plus harmonics: faint sounds produced by placing the fingers very lightly onto the strings instead of pressing down onto the fingerboard. These shifting sonorities serve to evoke the strange states of being Garrop had in mind while the many fast-paced passages and frequent fortissimo playing keep us simultaneously anchored in the here-and-now. Often the players are asked to “freeze,” incorporating sudden pauses into the music. A thematic three-note motive emerges at the start in the cello and the pianist’s left hand: starting on D, it moves up a half step, then down a whole step. Often hidden by other motives, it recurs steadily throughout each section to unify the work in the midst of often-wild commentary. The fourth section, marked Light and Playful, gives violin and cello a melody that’s soon echoed in the piano part. In section five, insistently repeated notes give way to a reiteration of the basic motive in the strings with wide octave displacement. This portion ends with a passage “like a machine out of control.” It’s succeeded by a rhythmically free, gorgeously serene passage before Tempo I returns “machine-like; reminiscent of beginning.” Playing pizzicato, violin and cello repeat the three-note motive very quietly while the pianist strikes the instrument’s lowest strings, and Seven ends “like a machine slowing to a stop.”

Album Details

Total Time: 67:20

Producer & Engineer: Judith Sherman

Assistant Engineer & Digital Editing: Bill Maylone

Editing Assistance: Jeanne Velonis

Front Cover Photo: Marc Hauser

Recorded: November 1-5, 2010 and April 15, 2011 in Bennett-Gordon Hall at Ravinia, Highland Park, IL

Steinway Piano Technicians: James Hudson & William Schwartz

Front Cover Design: Sue Cottrill

Art Direction: Inside Booklet & Inlay Card Nancy Bieschke

Publishers

Auerbach: Trio for violin, cello, and piano © 2009 Musikverlag Hans Sikorski GmbH & Co. KG, Hamburg

Garrop: Seven © 2000 Theodore Presser Co.

Higdon: Piano Trio © 2003 Jennifer Higdon

Schwendinger: C’è la Luna Questa Sera? © 2006 Laura Elise Schwendinger

Thomas: Moon Jig © 2005 G. Schirmer, Inc.

Tower: Trio Cavany © 2007 Associated Music Publishers, Inc. (BMI)

This recording is made possible in part through a generous grant from The Aaron Copland Fund for Music.

© 2011 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 126