Store

Store

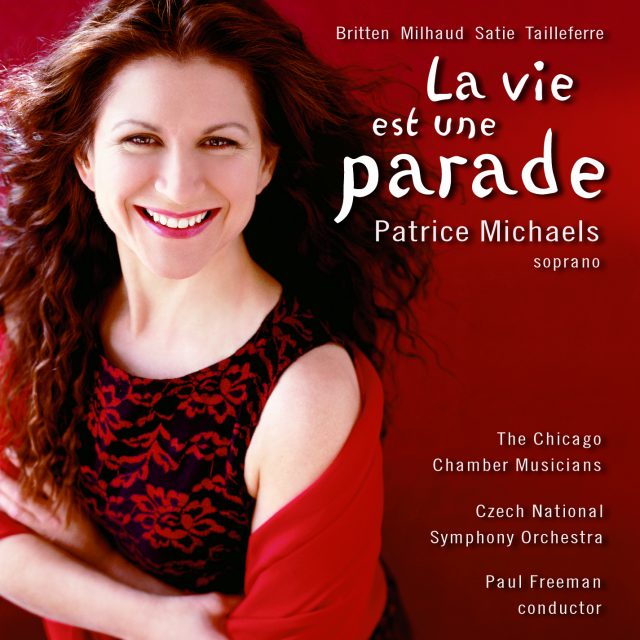

La vie est une parade

Chicago Chamber Musicians, Paul Freeman, Czech National Symphony Orchestra

This unique program features Benjamin Britten’s evocative masterpiece for soprano and strings, Les Illuminations, and Darius Milhaud’s rarely-recorded vocal tour de force, originally written for Lily Pons, Quatre Chansons de Ronsard; along with delightful rarities by Erik Satie and Germaine Tailleferre (the only female member of “Les Six”).

From Patrice Michaels:

“I fell in love with Milhaud’s music early in my singing life, and was privileged to perform these songs with the Montreal Symphony during my first international competition. The Britten setting of Rimbaud poems has also challenged and sustained me for some years now. I came to the world of song literature through my passion for theater and my fascination with folk music. The Tailleferre songs use deceptively simple material the way a master baker makes a baguette: the result appears inevitably natural and tastes irresistible. Satie’s songs are an amazing collection of dramatic wit and warmth that tie the whole program together the way wine and spices unify a meal. We might well have titled this disc “La vie est un repas,” except that the project really was a parade across continents, involving a legion of artists: we began performing and recording with the Czech National Symphony in Prague and ended in Chicago, assisted by the extensive vocal/instrumental archives of Editions Salabert in Paris. It was a sweet surprise to receive among the Tailleferre scores from Salabert four songs that were (to my knowledge) previously unrecorded. These, of course, joined the procession along with the newly made Satie arrangements from Easley Blackwood, all of which were a thrill for me to premiere with The Chicago Chamber Musicians. Performing this wealth of literature with so many great musicians has been a wonderful sojourn for me. I hope listening to it will prove equally rewarding for you. Bon appetit, and enjoy the parade!”

Preview Excerpts

ERIK SATIE (1866–1925) / EASLEY BLACKWOOD (b. 1933)

ERIK SATIE / ROBERT CABY (1905–1992)

GERMAINE TAILLEFERRE (1892-1983)

BENJAMIN BRITTEN (1913–1976)

Les Illuminations, Op. 18

GERMAINE TAILLEFERRE

ERIK SATIE / ROBERT CABY

DARIUS MILHAUD (1892–1974)

Quatre Chansons de Ronsard, Op. 223

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletLa vie est une parade

Notes by Erik Eriksson

Erik Satie (1866–1925): Songs

Perpetually stimulating for artists of all types, France’s blend of fresh thought and strong tradition is exemplified by Erik Satie. Throughout his creative life, Satie sought to avoid the inauthentic, the falsely emotional, the unobservant glance at the commonplace. In artistic circles, Satie was a peripatetic disturber of the peace. He is owed a great debt by countless others (including the group of subsequent French composers known as “Les Six”) who emulated and developed his ideas of harmony, melodic line, and musical architecture.

Satie’s music does not order itself into one style. The songs presented here include three parlor tunes alongside several miniature art songs. Tendrement and the forthright, heady Je te veux would be perfectly at home in a popular music hall, and La Diva de l’Empire could easily become a vehicle for a fin du siècle grisette. In the latter, however, Satie’s uncompromising compositional integrity helps his listener focus vividly on the “leetle girl” with the mocking smile. In the two waltzes, a predictable lilt never obscures Satie’s erotic intention and appreciation for his poets’ ability to surprise. For this recording, arrangements of La Diva and Je te veux were commissioned from composer Easley Blackwood.

Satie’s art songs have a bracing directness; they never dissemble. When the text ends, so does the music. Elegie is an unblinking, sad look backward, not without a certain theatricality. By contrast, Sylvie is a shy, adoring paean to a beloved, set over a modulating accompaniment moving in circular patterns. The art songs were arranged by Robert Caby (1905–1992), a composer and ardent admirer of Satie’s music. A former classmate of Jean-Paul Sartre, Caby knew Satie for little more than year, but became a close friend who devotedly visited the elder composer at Paris’s Saint-Joseph Hospital until Satie’s death on July 1, 1925. For the remainder of his own life, Caby kept fresh his devotion through the editing and orchestration of Satie’s works and by contributing numerous articles to music journals. Caby employed winds and strings (as does Blackwood) to expand upon, yet respect, the brisk simplicity of the original piano accompaniments. A subtle use of accent instruments (such as the clock-like percussion blocks in Daphéneo and the harp figures in Les Anges) keeps the music buoyant.

Germaine Tailleferre (1892–1983): Chansons du Folklore de France

Groves Dictionary of Music and Musicians, fifth edition, published in 1954, questioned the efficacy of Germaine Tailleferre’s gifts, describing her talent as “slender.” Since then, opinions of her work have become more favorable, although her music remains too little heard. For one thing, the composer, a member of “Les Six” (together with Georges Auric, Louis Durey, Arthur Honegger, Darius Milhaud, and Francis Poulenc) completed many significant works after 1954. For example, her 1981 Concerto de la fidélité pour voix élevée et orchestre won the 1982 Prix de la Ville de Paris. She also remained a force in pedagogy into her eighties.

Tailleferre’s arrangements of popular French songs transcend the usual genre but never overburden the melodies with orchestrations or harmonizations that detract from their vitality. The composer’s work here sparkles with the clarity of a perfectly cut gem stone. According to soprano Patrice Michaels, “the simple melodies are underscored, overlaid, and reworked with wonderfully complex harmonies, neatly and sparely orchestrated with an ensemble that seems at times transparent and at times surprisingly rich.” These songs offer no opportunities for technical display, but rather test the singer’s narrative gifts. Variety of vocal color is required in songs such as La Pernette se lève, where a dialogue between daughter and mother is in play. In these nine songs, life is often hard; pleasures are simple and to be taken whenever opportunity knocks (L’autre jour en m’y promenant). Tailleferre’s knowing way of scoring for woodwinds is everywhere evident. Whether plodding, marching, waltzing, or tripping along in 6/8 meter, the instruments propel in rhythmic figures as readily as they color the more sustained cadences.

Benjamin Britten (1913–1976): Les Illuminations, Op. 18

Through the friendship and influence of W. H. Auden, Benjamin Britten was introduced to the poetry of Arthur Rimbaud (1854–1891). Britten described Auden as “a powerful, revolutionary person,” and was deeply affected by the opinions and attitudes of this writer six years his senior. In 1977 (during a radio broadcast), Swiss-born soprano Sophie Wyss recalled that Britten had shared with her his excitement in having read Rimbaud’s Les Illuminations for the first time, declaring “I must put them to music.”

Wyss was the work’s dedicatee. She did not possess a particularly sensuous voice or extraordinary interpretive skills, but was nonetheless appreciated by many twentieth-century composers as a resolute advocate of their music (Rawsthorne, Milhaud, Berkeley, and Frank Martin among them). Britten admired her singing when he heard her in a London performance of Milhaud’s Pan et Syrinx and got to know her when she asked him to accompany her in a 1936 recital of Mahler, Walton, and Britten’s own song, “The Birds.” Wyss was impressed with Britten’s instinctive approach to music, his ease in accompanying, and his gift for extracting a wide range of colors from each orchestral instrument. When Britten, a resolute pacifist, decided to follow Auden to America, he left England in May of 1939, carrying with him the uncompleted score to Les Illuminations. Wyss introduced two of the songs before the full work was finished. In Birmingham and again at the Proms on August 17, 1939, the soprano sang Being Beauteous and Marine. Soon thereafter, Britten, residing with his partner Peter Pears in the home of Dr. and Mrs. William Mayer in Amityville, New York (on Long Island), finished the work: the date of completion was October 25, 1939. On the following January 30th, Sophie Wyss sang the premiere of the entire work in London, accompanied by the Boyd Neel Orchestra. Almost alone among British critics, Edward Sackville-West recognized the work’s quality, describing each piece as, “perfectly finished and original in character.” Critiques from other prominent reviewers betrayed both mistrust of Britten’s musical aims and resentment over his accelerating celebrity.

Britten’s scoring calls for first and second violins, violas, cellos, and double basses. Solo passages for violin occur throughout the work; viola solos are heard in IV, VII, and VIII and a solo cello passage informs VI. In IIIb, Britten specifies the balance he wishes, calling for four first violins, three violas, three cellos, and two double basses (second violins are silent).

Fanfare opens with upper strings sounding flurries of arpeggiated fanfares to herald the singer’s imperious announcement: “I alone have the key to this parade.” Next, over rushing, rustling cadences in the orchestra, the singer cries, “These are towns!” Disturbing towns, indeed. Phrase holds some of the blanched, unearthly orchestral timbres Britten was unique in conjuring. The singer rises sinuously to a very soft high B-flat, sliding quietly down to the B-flat an octave below. In Antique, the sensual text is limned over the small orchestra thrumming in 6/8 time (the score indicates “staccatissimo”). Royauté catches exquisitely the expansive mock solemnity surrounding the couple who would be royalty, wreathing it in swirling vocal figures. In Marine, the sea is invoked through a suggestive ostinato in the orchestra and a vocal line sharply accented (marked by eighth-note rests) and broken by more flights of ascending and descending scales. The Interlude that follows calls to mind the interludes Britten would compose for Peter Grimes a half decade later. The singer enters at the end to once more assert, “I alone have the key to this parade, this savage parade.” The text of Being Beauteous is graphically realized in the music: quivering and moaning in the 12/8 sostenuto of the orchestra under a restless vocal line in 4/4 meter. For the contemptuous lines of Parade, Britten provided a dark accompaniment in 2/2 meter, under a vocal part that is near speech in several low-lying passages. At the end, “I alone have the key” is heard yet again, as the singer finishes with a defiant, sustained “savage parade!” Départ concludes the work as singer and orchestra often move together, sounding satiated, spent: “Enough seen — Enough had — Enough known.”

Darius Milhaud (1892–1974): Quatre Chansons de Ronsard, Op. 223

Composed in 1941, the Quatre Chansons marked Milhaud’s second time setting a group of poems by Pierre de Ronsard (1524–1585). Milhaud wrote the set for and dedicated it to soprano Lily Pons, the diminutive fellow French artist who, a decade earlier, captured the hearts of New York audiences with her sensational debut at the Metropolitan Opera (the first major house in which Pons sang). As Donizetti’s Lucia in that January 3, 1931 debut, Pons’s gamin charm, crystalline voice, and extraordinary vitality instantly won the hearts of opera enthusiasts. She became a celebrity from coast to coast, charging fees among the highest of her time. At the Metropolitan Opera, her presence assured large audiences, making her central to that financially challenged institution’s survival during the decade following the crash of 1929. Pons premiered the Chansons de Ronsard on December 8, 1941 at New York’s Waldorf-Astoria Hotel.

Milhaud’s first response to Ronsard’s verse, Les Amours de Ronsard from 1934, was scored for vocal quartet or chorus accompanied by small orchestra. With the National Socialists developing their agenda in neighboring Germany, the mid-1930s were an uncomfortable time in France. These paled in comparison to 1941, however, by which time Milhaud had fled Nazi-held France to settle in Oakland, California as a visiting professor at Mills College.

One can only marvel at the composer’s ability to set aside personal turmoil and enter the world of a master poet of the French Renaissance. Ronsard was a member of the Pléiade, convened to replicate the purpose and accomplishment of classical writers. Many composers have been attracted to his verse including, from the poet’s own lifetime, Anthoine de Bertrand, Orlando de Lassus, Jean de Castro, and François Regnard; from the nineteenth century, Georges Bizet, Pauline Viardot, Jules Massenet, Richard Wagner, Cécile Chaminade, and Camille Saint-Saëns; and in the twentieth century, Francis Poulenc, Albert Roussel, Jacques Leguerny, Jacques Ibert, Arthur Honegger, Frank Martin, and Ned Rorem.

For this group of four songs, Milhaud designated an orchestra of strings, winds, brass, and percussion with the unusual requirement that the second clarinetist also play saxophone in the second and fourth songs. The singer’s tessitura is consistently, demandingly high. The first song, A une Fontaine, is a waltz of champagne lightness in which the singer evokes the magic of the fountain: source of refreshment, sacred place of repose, gathering place for nymphs to leap and revel. On the final word, the vocal line ascends to an A above the staff held for five measures and a quarter note. In A Cupidon, the singer chides Cupid for having aimed in her direction. The vocal line rises and falls in 9/8 time. Here, too, the song ends aloft; this time on a softly voiced B-flat. Tais-toi, babillarde is a plea to a noisy sparrow to hold his prattling song in the morning when Cassandre drowses by her lover’s side. As the orchestra pulses insistently, the vocal line bounces lightly through myriad roulades on its way to yet another high, soft ending, this time on high C. The final song, Dieu vous gard’ (God Keep You), celebrates spring’s arrival with a catalog of birds, flowers, butterflies, and flowing streams. Its vocal line soaring and twittering, the song advances quietly for the most part, growing to mezzo forte or double forte in only a few places. At the end, the vocal line flickers to B above the staff, then drops to a comfortable G, while the orchestra crescendos over the last two measures to a final, double-forte chord.

Erik Eriksson is music critic for Metropolitan Newspapers (Green Bay) and a major contributor to the internet-based All Classical Guide. He is a member of the Music Critics Association of North America.

Album Details

Total Time: 73:37

Recorded: November 5, 11 & 12, 2000 (with CNSO); March 25 & 26, 2002 (with CCM)

Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineer: Bill Maylone

Front Cover Photograph: McArthur Photography

Graphic Design: Melanie Germond & Pete Goldlust

PUBLISHERS: Satie/Blackwood: Blackwood Enterprises, Chicago. Satie/Caby: Editions Salabert, Paris. Tailleferre: Gerard Billaudot, Paris. Britten: Boosey & Hawkes. Milhaud: Boosey & Hawkes

© 2003 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 070