| Subtotal | $18.00 |

|---|---|

| Tax | $1.85 |

| Total | $19.85 |

Store

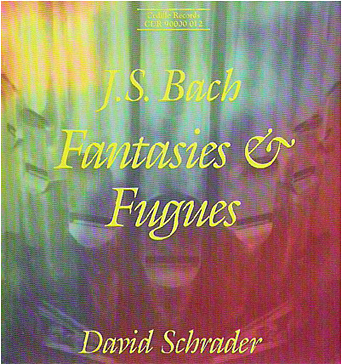

A major portion of JS Bach’s organ masterpieces — his complete Fantasies, Fantasies & Fugues, and isolated Fugues — is contained on this CD.

“The fantasies on this recording represent a wide range of composition, from the very freely composed to works that are obviously contrapuntal,” writes Schrader in the liner notes.

In this, his second Bach organ recording for Cedille, Schrader returns to the Jaeckel organ at the Salem Lutheran Church in Wausau, Wisconsin. Modeled on the late 17th-century northwestern German organs of Arp Schnitger, it’s the sort of instrument Bach knew well and made good use of during his career.

The organ is well suited to Schrader’s “unusually light and rhythmically quick pace,” writes Joseph Stevenson in Stevenson’s Classical Compact Disc Guide (July-September, 1992), in a perceptive review of Schrader’s complete Bach Toccatas and Fugues.

Critics have praised Schrader for eschewing the menacing, melodramatic, Phantom-of-the-Opera intonations of other Bach organists. Denver’s Rocky Mountain News noted with pleasure the absence of “heaven-storming theatrics”; the San Jose Mercury News said Schrader’s “minute rhythmic variations turn these familiar Bach works into a vivid listening experience”; and the Chicago Tribune lauded his “nimble-fingered panache.”

Preview Excerpts

JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH (1685-1750)

Fantasy & Fugue in G minor, BWV542

Fantasy & Fugue in C minor, BWV537

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletBach: Complete Fantasies and Fugues

Notes by David Schrader

The term fantasy (or fantasia) usually denotes a piece in which the composer is free from aesthetic constraints. From the sixteenth century onward, however, the term seems to indicate a piece which, although free of excessive constraints, is conceived contrapuntally. The fantasies of Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck (1562-1621) and composers of the English virginalist school are similar to the works which Mediterranean composers were calling ricercars. In any event, until the close of the seventeenth century, compositions which bear the title “fantasy” are basically imitative (the same themes are carried by different voices at different times).

During the final half of the seventeenth century, a style generally known as the stylus phantasticus, developed in what is now northern Germany. The stylus phantasticus emphasized a type of composition that was not always purely contrapuntal; it made use of musical materials designed to reflect caprice rather than consideration. Out of this tradition, which was so finely represented by Franz Tunder (1614-67), Dietrich Buxtehude (1637-1707), Nikolaus Bruhns (1665-97), Georg Böhm (1661-1733), Vincent Lübeck (1654-1740), and others, came the early works of Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750).

Bach’s predecessors tended to combine elements of extempore virtuoso playing and contrapuntal mastery in pieces called praeludia. Buxtehude, Lübeck, and Bruhns usually employed a five-part scheme that alternated freely composed sections (1, 3, 5) with fugal ones. Böhm favored a three-part form with the fugue placed between two freely composed sections.

It should be noted that the works Bach called “Fantasies” were often referred to as preludes in his day — nomenclature in the eighteenth century was far less dogmatic than it is today. The fantasies on this recording represent a wide range of composition, from the very freely composed to works that are obviously contrapuntal.

The Fantasy in C major, BWV 570, probably dates from 1704. Its melodic material, through-composed style, and ad libitum use of pedal (the pedal is used throughout the piece on this recording) are reminiscent of the works of Johann Pachelbel (1653-1706) and Johann Kaspar Fischer (c.1662- 1746).

The Fantasy and Fugue in G minor, BWV 542, were paired only after Bach’s death, and are believed to have been composed at different times. The fantasy probably dates from between 1708 and 1712. Its form represents a distillation of the five-part praeludium of Bach’s north German predecessors. The first, third, and fifth sections are freely composed and highly inventive, while the second and fourth sections are contrapuntal. The fugue, with its motoric rhythm and clear tonality, most likely comes from Bach’s later years in Weimar — sometime between 1712 and 1717. The fugue survives in seventeen different copies, one of whose scribes left the message, “in my opinion, the best work of Sebastian Bach with pedals.”

Although the Fantasy in C minor, BWV 562, was probably composed originally during the years 1706-1712, the version heard on this record comes from around 1730. This revised version had been paired with an even later but, regrettably, unfinished fugue.

The Piece d’orgue, BWV 572, is also known as the Fantasia in G major. With its five-part scoring in the central section marked gravement, the Piece bears some similarity to the early church cantatas of Bach’s Weimar period (1708- 1717), suggesting that it was written sometime between 1708 and 1712. The Piece is unique among Bach’s organ works for its form and French tempo indications.

The Fantasia con imitatione in B minor, BWV 563, with its circumscribed tonal direction and abrupt modulations, may have been composed as early as 1704 — about the same time as the Fantasy in C, BWV 570.

From Bach’s years in Leipzig (after 1723) we have the Fantasy and Fugue in C minor, BWV 537. The fantasy makes use of two rhetorical devices: the exclamatio — the upward melodic leap heard at the beginning of the work — and the suspiratio, identified by the two-note phrase that constitutes the piece’s secondary motive. The fugue is very closely related to the fantasy, which ends on the dominant chord to ensure the immediate and expected entrance of the fugue.

Bach’s independent fugues for organ are a highly diversified lot. The Fugue in C minor, BWV 575, has a concluding section in the stylus phantasticus tradition, suggesting that it is a relatively early work. Two of the fugues employ subjects taken from Italian composers, demonstrating Bach’s emerging interest in non-Germanic music. The mellifluous Fugue in B minor, BWV 579, is based on a theme by Archangelo Corelli (1653-1713), while the powerful Fugue in C minor, BWV 574 makes use of a theme by Giovanni Legrenzi (1626-1690). The “Legrenzi” Fugue is actually a double fugue that concludes with a stylus phantasticus ending much like that of the other independent fugue in C minor.

The lovely Fugue in G minor, BWV 578, is often referred to as the “Little G minor,” to distinguish it from the great Fantasy and Fugue in the same key. While the “Little G minor” is known to be by Bach, the Fugue in G major, BWV 576, known as the “Gigue” Fugue, is now of disputed authorship. It is included on this recording for its intrinsic merit and infectious rhythm, not merely for the sake of “completeness.” (Bach or no, it‘s a heck of a good piece!)

The first movement of the four-movement Pastorale, BWV 590, is the only one to require the use of the pedal, which plays, appropriately enough, pedal points (held notes over or under which harmonies change) — a hallmark of pastoral-type compositions of almost any period. The second movement also uses pedal points, but here they are played by the left hand. The third movement is a highly ornamented aria (cellists are fond of this movement in transcription because it presents such a lyrical example of the beauty and complexity of Bach’s ornate style). The finale is a lively fugal movement in binary form. For this recording, the doors of the organ’s Brustpositiv department (located directly above the keyboard) were partially closed to create an echo effect.

Album Details

Total Time: 74:51

Recorded: June 25 & 26, 1992 in Wausau, Wisconsin

Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineer: Bill Maylone

Front Cover: Photo by Eric S. Lieber

Design: Cheryl A Boncuore

Notes: David Schrader

© 1992 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 012