Store

Store

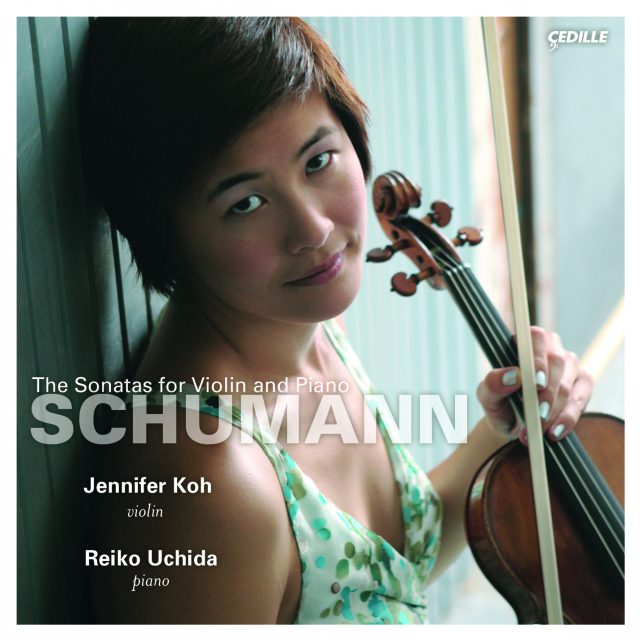

Schumann: The Sonatas for Violin and Piano

Playing and recording the Schumann Sonatas is one of my most personal projects to date. Schumann’s music has always compelled me as a musician and a listener for as long as I can remember. Schumann’s music is the most human with its viscerally haunting, obsessive, tender, and vulnerable extremes. One can connect a lifetime of experiences (birth, love, hate, death) into every phrase of his music. These disparate experiences are tied together into one life (one phrase, one movement, one sonata) in Schumann’s music. A single phrase is like a poignant memory that returns and with each visit is reborn more vividly, more passionately, more tenderly than before.

This recording is dedicated to the memory of Edward Aldwell. His warmth, generosity and wit are missed by all who knew him. His integrity and intelligence as a musician will always inspire us.

Preview Excerpts

Robert Schumann

Sonata No. 1 in A minor, Op. 105

Sonata No. 2 in D minor, Op. 121

Sonata No. 3 in A minor, WoO 27

Artists

Program Notes

View Album BookletSchumann: The Sonatas for Violin and Piano

Notes by Andrea Lamoreaux

Devotees of 19th-century Classical-Romanticism, on both sides of the music stand, have usually experienced uncomplicated enjoyment of Robert Schumann’s music, so beautifully melodic and passionately expressive. Academic commentators, on the other hand, have been known to tie themselves up in knots about it, by turning musical analysis into after-the-fact psychoanalysis, thus adding complication instead of casting light. Knowing that Schumann showed symptoms of mental instability from as early as 1828, when he was in his late teens; that his struggles with depression were likely one reason Clara Wieck’s father didn’t want her to marry him; and that he died at age 46 confined to an insane asylum after a suicide attempt — some historians have sought to evaluate his works in terms of mental aberration. An awkward orchestral passage or meandering piano piece can thus be fitted into an overall theory that posits a composer beset by psychological obstacles and unevenness of focus.

While there can be no doubt that a composer’s personality influences his or her style, the sometimes-obsessive concentration on Schumann’s mental state at various stages of his sadly short life has tended, at times, to obscure some plain facts: his music is challenging and involving to play, rewarding and enjoyable to hear. And, oddly, some of it remains relatively unknown. Despite explorations in concert and on recordings of lesser-known works such as the ambitious Scenes from Goethe’s Faust, we usually think of Schumann in terms of the magical, youthful piano suites like Carnaval, the lyrical song outpourings of 1840 (the year of his marriage to Clara), the four symphonies, the Cello Concerto, and the beloved Piano Concerto. In addition to these standards, most of his chamber music has remained in the repertory: his string quartets, Piano Quintet, and duo works such as the Three Romances (oboe and piano), Adagio and Allegro (horn and piano), and fairy-tale works involving viola. But his sonatas for violin and piano? They’re out there, they get played, but they’re also new discoveries for many of us.

All three violin sonatas date from Schumann’s rather unhappy time as general music director for the city of Dusseldorf, a tenure that began in 1850. Never an outstanding conductor, he was in constant conflict with the city’s orchestra and its administrators. But this time in his life was extremely productive for composition. He wrote his Symphony No. 3, the “Rhenish,” revised an earlier symphony that became No. 4 in D Minor, initiated a number of choral projects, and returned to the realm of chamber music for the first time in several years. The opus-numbered Violin Sonatas — Op. 105 in A Minor and Op. 121 in D Minor — both date from 1851. They were first performed in private settings, later in public, with Clara at the piano in partnership with good friends who were also exceptional violinists: Joseph Wasielewski from Mendelssohn’s Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, who would be Schumann’s first biographer; Ferdinand David, the Gewandhaus concertmaster, to whom were dedicated both Mendelssohn’s E Minor Violin Concerto and the second Schumann sonata; and Joseph Joachim, the young virtuoso who would become a colleague and friend of Brahms, and who would also partner with Clara in many recitals as she continued her concert career after Schumann’s death. Joachim was also, in a sense, the inspiration for Schumann’s third violin sonata, two movements of which originated in a collaborative work he wrote with Brahms and another colleague to honor their violinist friend.

The three sonatas, while all quite different, have characteristics in common. One that stands out immediately is the prominence of the piano. These are all true duo-sonatas, emphasizing each instrument in turn. The keyboard player may sometimes introduce a theme or its variant, take over a passage from the violinist, or offer elaborations in striking contrast to the violin’s progressions. Another element that emerges is the almost-constant shifting between major and minor modes. Each sonata is cast in a minor home key — A Minor, D Minor, A Minor — and following the traditions of sonata form in his first movements and elsewhere, Schumann generally casts the second, contrasting section in the major mode. But the motives refuse to stay in their traditional places. Throughout each sonata, there is an almost constant shifting between major and minor, a progression that contributes to the feeling of steadily-evolving thematic exploration. This links to another element these works share: the recalling of themes and motives from earlier movements to unify each sonata in subtle yet strong connections. And each has a headlong, rhapsodic nature only briefly interrupted by passages of serenity, tending to make those calmer sections, such as the variations in the Second Sonata, stand out even more.

The first movement of the First Sonata is more than adequately characterized by its tempo indication, which translates as “With Passionate Expression.” Rhapsodic and lyrical, its pace is largely determined by the prevailing rhythmic unit: rapid 16th notes. It is virtually monothematic: the agitated and expressive A minor tune introduced in the violin’s lower register persists almost throughout. The modulation of this theme to the relative C Major is standard procedure, but the persistent major-minor fluctuation makes the delineation of sections unclear and gives us an impression of constant variation. Also standard procedure is the progression from A Minor to A Major in the recapitulation; but whereas Mozart, for example, might have ended the movement in A Major, Schumann reinforces the passionate nature of the entire movement by a sudden and emphatic return to the minor.

The Allegretto movement, much more serene in character, is in the nature of an Intermezzo or a gentle Scherzo. The key fluctuates among F Major, C Major, and F Minor. Once again, there is basically one theme, elaborated and expanded through violin ruminations. The piano seems more of an accompaniment here, but it is the keyboard that first states the assertive main theme of the A Minor finale. The violin quickly takes it up, and runs with it; as with the first movement, the predominant rhythmic unit is the 16th note. A short and concentrated finale, this “Lebhaft” (Lively) movement is structured as a Rondo, with a major-mode additional theme set against the recurrences of the opening melody. Toward the end, Schumann dramatically recalls the main theme of the first movement, tying all his thematic threads together.

In its juxtaposition of the keys of A Minor/A Major and F Major/F Minor, the First sonata harks back to Schumann’s three string quartets of the early 1840s, and to the Piano Concerto of the same decade. The key of D Minor, meanwhile, had special personal resonance for Schumann, as it did for Mozart, implying unusual depth of emotion. The second violin sonata, in D Minor, is much more expansive than the concentrated First Sonata. Schumann dubbed it Grand Sonata, and in both length and expressiveness, it fully qualifies for the name. The first movement alone is nearly as long as the entire First Sonata. After a flourish of chords and octaves, the violin plays a slow (Langsam) introductory melody that recalls operatic recitative. The main section of the movement, marked Lebhaft or Lively, presents two vigorously-contrasted themes that are each extensively developed and recombined. Once again the mode shifts continually between minor and major, and related keys are tantalizingly explored. The piano often takes the lead in this movement. The violin has a characteristic motto, an upward run, but basically stays in its middle register. D Major appears to be the intended key of the final part of the recapitulation, but as with the First Sonata, Schumann asserts the minor at the movement’s close.

This sonata has both a Scherzo and a slow movement, unlike the First Sonata (where those functions were more or less combined in the Intermezzo). Moving rapidly in 6/8 time, the Scherzo contrasts two themes that culminate in a quotation from the traditional chorale “Gelobet seist du, Jesu Christ” (All praise to you, Jesus Christ).

The chorale melody — a gorgeous tune — then becomes the basis for a remarkable set of variations in the slow third movement. The piano introduces the theme with the violin playing pizzicato over it. Then the violin takes up the theme with the bow, playing it first as a single line, then in double-stops. G Major shifts to minor as the variations unfold, and the insistent triplet patterns from the Scherzo are brought back to link these two central movements both rhythmically and thematically.

The final movement is marked “Bewegt”: moving. Move it does, almost in perpetual motion, with an emphatic opening theme repeated and insisted upon by both instruments at the very beginning, then reiterated after contrasting motives in a quasi-Rondo structure. The concluding key is a triumphant D Major. The piano figurations are especially interesting in this movement: running and rippling for measure after measure, they are often suddenly punctuated by bravura octave passages.

The collaborative F-A-E Sonata was written for Joseph Joachim in 1853. Albert Dietrich (an otherwise unremembered composer) contributed the first movement; Brahms offered a Scherzo, which is often played nowadays as a separate piece; and Schumann composed an Intermezzo and a Finale. The letters F-A-E stand for a motto Joachim adopted, “Frei Aber Einsam,” Free But Lonely. Those letters, of course, are also musical notes, and they are combined to form motives of the work. After the gift was presented, Schumann decided to add two movements of his own to the Intermezzo and Finale to construct a third, all-Schumann, violin sonata. It has been suggested that Clara suppressed this little-known work because it brought back painful memories of her husband’s final years. In any event, it was not published until 1956 and is still seldom played.

In some respects this sonata (A Minor once again) resembles the D Minor work in its expansiveness, emotional range, and layout in four movements, the first with a slow introduction. This opening, dramatic and emphatic, is characterized by flourishing runs for the piano and energetic leaps in the violin part, a technique little used in the other two sonatas. The wandering through keys, and back and forth between major and minor, remains characteristic. A triumphant climax is reached via piano octaves and violin double-stops. The Scherzo opens with the violin playing a theme that’s related to the main theme of the first movement. The string player definitely leads in this movement, especially in the brief, songlike midsection. The Intermezzo is even more song-like. It’s not really a slow movement — the tempo marking is “Moving” — but its mood is one of serenity and gentle melancholy. The piano briefly picks up the main melody as the violin meditates gently above it. The finale begins as a march and presents its themes with strong rhythmic emphasis throughout. Contrasting with this overall texture is an almost cadenza-like passage for the violin, playing elaborate runs over a piano statement of the main theme. The movement’s coda, highly dramatic and rhapsodic, is a sheer celebration of sound.

Andrea Lamoreaux is music director of 98.7 WFMT-FM, Chicago’s classical-music station.

Album Details

Total Time: 66:39

Producer & Engineer: Judith Sherman

Assistant Engineer: Jeanne Velonis

Graphic Design: Melanie Germond

Artist Photos: Janette Beckman

Recorded:

Sonatas Nos. 1 and 2 recorded May 27-29, 2005 in Theater A, Performing Arts Center, SUNY, Purchase, NY

Sonata No. 3 recorded June 1 & 2, 2006, in the American Academy of Arts and Letters, New York City

Microphones: Schoeps MK2, Sonodore

Steinway Piano

© 2006 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 095