Store

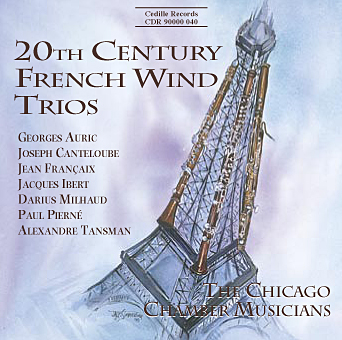

An attractive and neglected area of 20th-century repertoire gets its due on this CD that toasts French composers and their delightful wind trios.

On its second outing for Cedille Records, The Chicago Chamber Musicians — in this instance, a subset comprising oboist Michael Henoch, clarinetist Larry Combs, and bassoonist William Buchman — perform eight sparkling wind trios composed expressly for that instrumentation in the 1930s and 1940s by Paul Pierné (not his better-known cousin, Gabriel), Canteloube, Ibert, Milhaud, Tansman, Auric, and Françaix.

“The airy delicacies on this new CD exude traditional Gallic spirit: clear textures, brilliant colors, and sparkling wit,” says producer James Ginsburg.

Preview Excerpts

JEAN FRANCAIX (b. 1912)

Divertissement

DARIUS MILHAUD (1892-1974)

Suite d apres Corrette

JOSEPH CANTELOUBE (1879-1957)

Rustiques

ALEXANDRE TANSMAN (1897–1986)

Suite pour Trio d Anches

JACQUES IBERT (1890–1962)

Cinq pieces en trio

PAUL PIERNE (1874-1952)

DARIUS MILHAUD (1892-1974)

GEORGES AURIC (1899-1983)

Trio

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album Booklet20th Century French Wind Trios

Notes by Andrea Lamoreaux

“His music is characterized by an engaging spontaneity and great technical proficiency. It is often witty . . . not self-consciously neo-classic, but marked on the whole by a classical restraint and sobriety — in a word, by those qualities of clarity, proportion, and elegance which have always been the hallmark of the Gallic spirit in the arts.” — Critic Rollo Myers on Jean Françaix

Professor Myers might well have been writing about all of the composers represented on this CD, not just Françaix, especially in his references to wit and spontaneity, and to the restraint that takes its inspiration from 18th-century Classicism, rather than the 19th-century Romantic age. Above all stands out that word “clarity,” so often used to describe the music of France. The fondness for woodwinds that so many French composers have shown may be accounted for in part by this paramount desire to achieve clarity of sound, expression, and tone color.

Jean Françaix (b. 1912) was still a schoolchild in the early 1920s, when Stravinsky, Schoenberg, and others were radically transforming the sounds and styles of music. A graduate of the Paris Conservatory, Françaix also studied with Nadia Boulanger, the famous and highly influential teacher of numerous aspiring European and American composers (including Aaron Copland, David Diamond, and Easley Blackwood). First achieving fame at age 20 with his Concertino for Piano and Orchestra, Françaix has gone on to write music for ensembles large and small, for voices, and for solo instruments.

The Schott music publishers have issued a complete catalog of Françaix’s works, with an anonymous biographical note as introduction. The unknown author writes: “[Françaix’s] works are typically French — they have charm, spirit, and grace; they are often touched by irony . . . they show their creator’s innate sense of humor . . . [it is the work of one] who, through his cultured conception of the musical art, is a spiritual brother to Debussy and Ravel.”

Divertissement (Entertainment) would be an appropriate title for most of Françaix’s works. In this case, it is a four-movement, three-sided conversation that goes through various topics and climates: a moderately-paced opening, a succeeding section of complex and competitive chatter, a brief lament, and a light-hearted, virtuosic conclusion.

“Others write music to express ourselves,” Aaron Copland once said; “Milhaud, like no other composer I know, writes music to celebrate life itself.” We can imagine that Darius Milhaud (1892– 1974) would have enjoyed the exuberant song “L’Chaim” (To Life) from Fiddler on the Roof, because it would speak to the Jewish heritage that was so important to him, and for its theme of cheerful courage in the face of adversity — an attitude that characterized his own outlook. Milhaud was bedeviled by poor health for most of his life, but did not let that prevent him from composing hundreds of works; multifarious scores in many different styles for the stage, films, voices, orchestras, chamber groups, and keyboards made him one of the most prolific composers of the 20th century. And he was able to work productively anywhere: Paris, his beloved native Provence, South America, or California, which became his home for several years after his emigration from World War II France.

Milhaud and Georges Auric (also featured on this disc) were members of Les Six, a group of young, iconoclastic composers who emerged in Paris in the 1920s, voicing opposition to the music of France’s past: in their words, “the eloquence of Franck, the impressionism of Debussy, and the scholasticism of D’Indy.” The other members of this famous sextet were Francis Poulenc, Arthur Honegger, Germaine Tailleferre, and Louis Durey. They experimented with all kinds of musical endeavor, from opera to jazz; they defied convention and took special pleasure in shocking — exhibiting an attitude Prokofiev called (in reference to his own music) “teasing the geese.”

Milhaud’s wind trios, the Pastorale and the Suite d’après Corrette, do not share the aggressive modernism preached by Les Six; they reveal instead the composer’s firm roots in the musical past, and his interest in both folk music and the composers of the French Baroque. The Suite originated as music for a Frenchlanguage production of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, staged in Paris in 1937. Milhaud’s inspiration was the early 18thcentury composer Michel Corrette. In its non-stage form the music takes the shape of a neo-Baroque suite of dance pieces, interspersed with self-described sections such as the Fanfare, the gentle Serenade, and the graphic Cuckoo finale. The tiny Pastorale is a kind of miniature prelude and fugue in which the oboe takes the leading role; its mood and atmosphere are amply described by the title.

The French pastoral tradition is also represented in the trio by Joseph Canteloube (1879–1957), whose art took its inspiration from his country’s history and folklore, particularly that of his native region, the district of south-central France known as the Auvergne. Like Bartók and Kodály in Hungary, and Ralph Vaughan Williams in England, Canteloube traversed the countryside noting down traditional songs and dance tunes. His arrangements were published in several collections called Songs of the Auvergne.

As an anonymous biographical note in Grove’s Dictionary of Music declares, “[Canteloube’s] settings of folksongs . . . have gained widespread favor, but his original works have been neglected.” The Chicago Chamber Musicians remedy this situation somewhat with Rustiques, a three-movement evocation of the riches of Gallic folk music every bit as eloquent in the instrumental realm as the Auvergne songs are in the vocal. Especially lovely is the central Réverie that recalls the limpid serenity of a favorite among the songs, Bailerò (Shepherd’s Melody).

All of the composers on this recording were born in France except Alexandre Tansman (1897–1986), a native of Poland who attended the Lodz Conservatory and Warsaw University before moving to Paris in 1919, where he became part of Milhaud’s circle. He also befriended another emigré musician, Igor Stravinsky (Tansman published a biography of Stravinsky in 1948). While Tansman was more famous as a concert pianist and conductor than as a composer, his list of works is lengthy and varied, including film music from his sojourn in the United States during World War II.

Like Stravinsky’s music, Tansman’s Suite pour Trio d’Anches (Suite for Wind Trio) places great emphasis on the element of rhythm. Laid out in four short movements arranged slow-fast-slow-fast in the manner of a Baroque trio sonata, the Suite features frequent ostinatos (repeated rhythmic figures) and passages contrasting slow-moving patterns with rapid ones. Movement titles are self-descriptive. Particularly moving is the Aria, which is highlighted by a wandering, mournful oboe melody.

Jacques Ibert (1890–1962) was a central and highly influential figure in French musical life during the first half of the 20th century whose music has survived in the repertoires of both orchestras and chamber groups. A decorated officer in the French Navy during World War I, Ibert made his name between the wars as a composer of operas and symphonic works (notable among the latter is Escales, Ports of Call, inspired by his seafaring experiences), and also explored the thennew world of film music. In 1937, he became director of the French Academy in Rome, a post he held until 1960 — except for the World War II years, when he was persona non grata to both Mussolini and the Vichy regime. Ibert’s most famous composition for winds is his Trios pièces brèves for woodwind quintet. No less sparkling are the miniatures he titled Cinq pièces en trio. Contrasting fast and slow tempos, the pieces present inviting tunes intricately intertwined up and down the entire range of the instruments. The quasi marziale finale is a very jolly march, with a folk-like theme that suggests more a hike in the country than a military parade.

The Chicago Chamber Musicians’ journey through modern French wind trios began with a virtual “mystery” composer: the nearly forgotten Paul Pierné (1874– 1952), a younger contemporary of Debussy, and cousin to the better-known Gabriel Pierné. A graduate of the Paris Conservatory, winner of the prestigious Prix de Rome, and longtime organist at Paris’s Church of St. Paul and St. Louis, Paul Pierné wrote operas, symphonic poems, songs, and — naturally — quite a bit of organ music. Despite his productivity, virtually none of his music survives in the standard repertory.

Pierné’s Bucolique variée gives a simple, lyrical melody first to the bassoon, then the oboe, with the clarinet providing commentary; the theme is varied with increasingly complex melodic figurations and rhythmic patterns, until simplicity returns at the end. The word Bucolique may be translated as Pastoral Piece.

Georges Auric (1899–1983) was, like Tansman, closely associated with Stravinsky, and also played a major role in the history of French movie-making, composing several scores for films by Jean Cocteau. A sort of junior member of Les Six — Milhaud, Poulenc, and Honegger are viewed as the group’s most significant figures — Auric combined a distinguished career as a music critic with his work as a composer. He has several ballets to his credit, plus orchestral pieces, numerous songs, and quantities of piano and chamber music.

The clarinet takes the initial lead in the dancing, vibrantly rhythmic first movement of Auric’s 1938 Trio. The very lyrical Romance combines the instruments with intertwining melodies; the word expressif and the dynamic marking piano (soft) pepper the movement’s final pages. The final portion of the trio contrasts playful triplet patterns with quieter, more sedate interludes.

Andrea Lamoreaux is Programming Executive at Fine Arts Station WFMT-FM in Chicago.

Album Details

Total Time: 78:35

Recorded: Oct. & Dec. 1997 at WFMT Chicago

Producers: James Ginsburg & Burke Morton

Engineer: Bill Maylone

Production Assistant: David Dieckmann

Cover Painting: Jack Simmerling

Design: Cheryl A Boncuore

CDR 90000 040