Store

Store

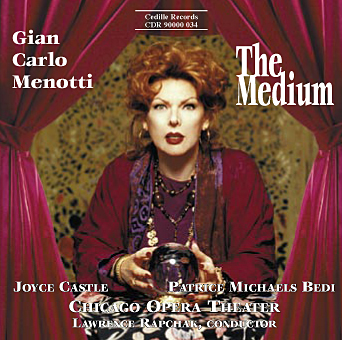

Gian Carlo Menotti: The Medium

Patrice Michaels, Lawrence Rapchak, Barbara Landis, Diane Ragains, Joyce Castle, Peter Van De Graaff

Oft-performed but mysteriously absent on recordings, Menotti’s eerie opera The Medium has materialized in its first recording in more than a quarter century. This two-act “musical drama” is about a fake psychic whose surprise encounter with the unknown leads to murder and mayhem. It is stage a dozen times annually in the US alone. Yet, recordings haven’t been available for years, and (until now) it has never appeared on CD.

A “sensational success” for Menotti (Kobbé’s Opera Book), the present version of The Medium had its premiere February 18, 1947 at New York’s Heckscher Theater. New York Times music critic Olin Downes wrote, “we have here the quality of opera. It is dramatic music, emphatic in action as well as feeling, and in essence song, which is what opera must be. No other American composer has shown the inborn talent that Mr. Menotti, an Italian by descent, unquestionable possesses for the lyric theater.” Critic (and composer) Virgil Thomson called it a “first-class musico-theatrical work . . . the most gripping operatic narrative [he] has witnessed in many a year . . .[It] wrings every heart string, and the music is thoroughly touching.”

Its success led to Broadway, where it opened on May 1, 1947, at the Ethel Barrymore Theater for a run of 211 performances. “Deaf (in the musical sense) as I am,” wrote Saturday Review’s drama critic, John Mason Brown, “I responded to Mr. Menotti’s score and felt its rightness for its book . . . they fused with arresting results.” New Yorker drama critic John Lardner described “an enraptured audience, which kept shouting ‘Viva!’, ‘Encore!’, and even, now and then, ‘Bis!'”

In Cedille’s recording, Miss Castle brings to the title role a finely crafted interpretation developed through two stage productions comprising more than forty performances. A favorite of the Metropolitan and New York City operas, she has performed and recorded a wide variety of 20th century music. Her association with the operas of Menotti, which began early in her career, includes The Saint of Bleecker Street, The Consul, and The Old Maid and the Thief.

As Monica, Miss Michaels reprises the role she played with great success in Chicago Opera Theater’s 1992 production. The Chicago Sun-Times wrote, “Patrice Michaels Bedi offered a deft balance between innocence and knowledge. Her bright soprano was a ray of youthful sunlight.”

The 1992 production, which likewise featured Miss Ragains in the role of Mrs. Gobineau, was the genesis for Cedille’s recording, according to label producer James Ginsburg.

Produced by Ginsburg and recorded by Grammy award-winning engineer Lawrence Rock, Cedille’s The Medium includes sound effects (gunshots, the cracking of a whip, and more) to aid the listener’s imagination, in the tradition of radio drama. Ginsburg explains, “After the music was recorded, effects were added to emphasize events, gestures, and emotions, and to help create an atmosphere of dramatic immediacy.” Scenes involving movement were blocked out and performed before an array of microphones for added realism, Ginsburg says.

Preview Excerpts

GIAN CARLO MENOTTI (b. 1911)

Act I

Act II

Artists

Program Notes

View Album BookletGian Carlo Menotti’s The Medium

Notes by Andrea Lamoreaux

Despite its eerie setting and gruesome conclusion, THE MEDIUM is actually a play of ideas. It describes the tragedy of a woman caught between two worlds, a world of reality which she cannot wholly comprehend, and a supernatural world in which she cannot believe.

— Gian Carlo Menotti

In the 1990 movie GHOST, the main character is killed in a mugging. Dead at the feet of his girlfriend, he enters into existence as a ghost: able to move about the streets, and to see and touch his beloved fiancée. She, however, cannot see him, or respond to his caresses, or hear his voice. Desperate to communicate, he visits a psychic, a woman who claims she can contact the spirits of the dead. Upon meeting a true ghost, she nearly has a nervous breakdown; instead of manipulating living clients into seeing ghosts that aren’t there, she now finds herself persuaded to convey urgent messages from a real ghost who is manipulating her. The psychic’s successful transformation from con to conduit is, arguably, the most absorbing and memorable aspect of the film.

But for Madame Flora, the fake psychic who headlines Menotti’s opera, an encounter with a perceived supernatural force leads to disaster. Her fear of the unknown and helplessness upon experiencing something she has not planned and cannot understand, causes her whole world to spin out of control.

The particular language of seances, in which people try to communicate with the dead through the aid of a medium or intermediary, gives special meaning to the word “control”: a medium is more psychically articulate than others, allegedly able to bring forward the spirits of dead loved ones. Madame Flora’s seances do not literally posit this kind of controlling spirit, but for her, control is still everything. She has two accomplices in her profession of deception: her daughter, Monica, whose job is to fake ghostly apparitions and voices, and Toby, a mute boy who stages supernatural effects for atmosphere. She believes she has the two young people totally under her thumb, that they will do anything she tells them, being merely living stage props for the con.

And she has control not only over her crew, but also over her clients — who are so grief-stricken over the loss of people they love, that they will believe anything. They both want and need to believe in Madame Flora.

Then, in the midst of a routine evening, just another seance — looking forward, perhaps, to laughing at the fools once they pay their money and depart — Madame Flora feels the touch of a cold hand on her throat. She is terrified. Her clients are within sight, motionless, mesmerized; Monica is off in a corner, imitating a ghost; Toby is behind a curtain. Yet someone or something has touched her. She is no longer in control, and she is transformed from a purveyor of the inexplicable into a relentless seeker after an explanation.

Menotti himself analyzed the disintegration of Baba, as her daughter calls her, in these words:

“[She] has no scruples in cheating her clients…until something happens which she herself has not prepared. This insignificant incident, which she is not able to explain, shatters her self-assurance and drives her almost insane with fear. From this moment on, she rages impotently against her still credulous clients, who are serene in their naive and unshakable faith, and against Toby…who seems to hide within his silence the answer to her unanswerable question….Monica, in the simplicity of her love both for Toby and Baba, tries to mediate between them. But Baba, in her anxiety and insecurity, is finally driven to kill Toby, ‘the ghost,’ the symbol of her metaphysical anguish, who will always haunt her with the riddle of his immutable silence.”

Toby, of course, can neither deny nor confess any mischievous interference with the events of the staged seance. He cannot speak in his own defense. Monica is helpless to defend him or to comfort Baba, whose fear she does not understand, and Baba is helpless to overcome her terror and guilt. Obsessed with regaining control over her increasingly chaotic world, she destroys all by a murder that gives no answer at all except Toby’s dead body, with a mouth that spoke no words this side of the grave, and will never speak from beyond it either.

Menotti wrote both the words and the music for The Medium. Here he describes its genesis:

“Although the opera was not composed until 1945, the idea… first occurred to me in 1936 in the little Austrian town of St. Wolfgang near Salzburg. I had been invited by my neighbors to attend a seance in their house. I readily accepted their invitation but, I must confess, with my tongue in my cheek. However, as the seance unfolded, I began to be somewhat troubled. Although I was unaware of anything unusual, it gradually became clear to me that my hosts, in their pathetic desire to believe, actually saw and heard their dead daughter, Doodly (a name which I retained in the opera). It was I, not they, who felt cheated. The creative power of their faith and conviction made me examine my own cynicism and led me to wonder at the multiple texture of reality.” (Emphasis added)

Baba, unlike Menotti, cannot confront her cynicism, and is incapable of contemplating the “multiple texture of reality”. She reacts to the phantom touch with panicky fear, which bewilders her three clients: Mr. and Mrs. Gobineau, who attend the seances to hear the happy laughter of their son Mickey, who drowned accidentally at the age of two, and Mrs. Nolan, a newcomer who wants to contact her daughter.

After the clients have been sent away, Baba panics again, with a sudden, almost comic attack of conscience: “we must give their money back.” She derives some comfort from Monica, who sings a sad ballad called “The Black Swan”; its slow rhythms and mournful tune, its focus on death, seem somehow to calm her, and the song ends as a duet.

But the calm does not last long, for while Monica is still singing, Baba seems to hear ghostly laughter and the voice of a young girl. In terror, the medium turns to prayer — perhaps for the first time in a long while — yet over her voice reciting the “Ave Maria” we still hear, as she does, the faint laughter.

In the staged seances, of course, it is Monica who produces the otherworldly voices — but now? Is it her imagination, or a trick, or is there something there?

An opera takes shape through its music, its plot, its characterizations, and finally, its stage setting: scenery, costumes, props, lighting, and the actions of the performers while they are singing. Though the music of an opera conveys a good deal of its drama — and while some opera-lovers claim to care only about the singing — it is inevitable that some of the impact of the whole operatic creation is lost on a recording. It is left to our imagination to re-create Baba’s shabby flat, her gypsy-colored clothing, the haunted and eager faces of the clients, the white robes that turn Monica into a floating spirit.

To aid the imagination and to enhance the sense of true music theatre, this recording of The Medium has added sound effects to highlight some of its important events. Producer James Ginsburg says: “I conceived this recording as a kind of radio play, a performance in which our ears are the sole receptors of impressions that in an actu – al theatre would come through both ears and eyes. Sound effects are used in radio plays, and they have been similarly used in this production of The Medium. After the music was recorded, effects were added, to emphasize events, gestures, and emotions, and to help create an atmosphere of dramatic immediacy.”

SYNOPSIS OF THE OPERA

The short overture to Act One creates an instant sense of foreboding; the first vocal music, “Where are my new golden spindle and thread,” gives us an immediate clue to the character of the singer, Monica. Her music is almost always simple and folklike, and shows a romantic, fairy-tale imagination utterly at odds with the cynical use her mother makes of her.

The young people play games together instead of preparing for the evening’s seance, but in the music we hear the sudden slamming of the door. Baba appears, angry that nothing is ready and that Toby has been costuming himself in her clothes. She has been out to collect money from a former client, and triumphantly slaps it down on the room’s big table to announce her success.

The seance preparations, now quickly made, include thin wires attached to the table, which Toby surreptitiously pulls from behind the curtain of a puppet theatre. Monica wears the ghostly veils. She and Toby are hidden by the time the shrill call of the doorbell announces the arrival of Mr. and Mrs. Gobineau and Mrs. Nolan.

The Gobineaus reassure Mrs. Nolan that they have never failed to hear the voice of their Mickey. As the lights are lowered and the seance begins, Baba begins to moan eerily, and Monica becomes visible in the corner: “Mother, mother, are you there?”. Mrs. Nolan believes this is her dear Doodly, and Monica sings to her about putting away her grief; she is happy where she is, only her mother’s sadness makes her sad too. Once again, the musical style for Monica is simple and gentle, even though she is expressing more complex emotions in this aria.

Mr. Gobineau now begs for his son, and faint childish laughter is heard. The illusion is complete, when suddenly Baba screams: she has felt the touch of a cold hand, and now nothing can be the same for her.

Stamping and shouting, Baba insists that the clients leave, and we hear the door once again as they depart in bewilderment and distress. Baba is hysterical; with a violent gesture she pulls back the curtain of the puppet theatre to accuse Toby of trying to frighten her.

Act One draws toward its close with the “Black Swan” aria and duet; it is almost the last period of serenity in the opera, as Toby, in spite of Baba’s accusations, joins in the performance. He cannot sing, but he plays along with the women softly on a tambourine. The act ends with eerie voices and laughter that only Baba, praying frantically, can hear.

The same ominous chords heard at the beginning of Act One open Act Two. Once again Toby and Monica are alone together; he is entertaining her with a puppet play, characterized by lively woodwind music, and she rewards him with a waltz song that becomes a one-sided love duet. Once again, the music reveals the girl’s shining, innocent goodness. As Toby dances for her, and then kneels at her feet, Monica not only tells him of her love, but speaks for him, of the love she realizes he feels for her.

The door slams; Baba has returned. She has turned from the conscience-stricken remorse and prayerful pleading at the end of Act One to an old refuge: drink. Monica has fled to her room, and Baba is alone with Toby. In the most lyrical music so far, she reminds the boy how she has cared for him all his life, and promises to reward him if he will just confess that he tried to frighten her with a ghostly touch. The boy makes no sign either to acknowledge or deny, and Baba again becomes violent; the boy’s shirt is suddenly ripped from his back, and in final desperation, Baba grabs a whip to beat him. Will she beat him to death? She does not get the chance, because the doorbell shrills again, to announce the return of the Gobineaus and Mrs. Nolan. Baba has forgotten there was supposed to be a seance tonight.

Once again we hear money being slapped down on the table; Baba confesses the deception, concluding with, “There is your money.” But the clients refuse to believe that they have not seen and heard their beloved dead children, not even when Monica demonstrates Doodly’s song and Mickey’s laugh. As Mr. Gobineau puts it, “It might well be you thought you were cheating us all the while, but you were not, you were not.” They plead for one more seance, but Baba drives them out mercilessly. She also turns once again on Toby, drives him away too, and locks Monica in her room.

Alone, in a drunken, grieving stupor, she recalls the poverty and degradation she witnessed in her youth, but those terrible things never made her afraid; why is she afraid now? Once again she prays, for forgiveness this time, and then falls asleep. Toby now creeps back; he scratches gently on the locked door, but there is no response. He runs behind the couch when Baba knocks over the bottle she had been drinking from, but emerges when he sees she is still asleep. Tiptoeing behind Baba, he heads for the trunk where he keeps his tambourine; when he accidentally drops the lid, with a loud crash, Baba awakens. Toby hides behind the curtain of the puppet theatre, so Baba sees no one; she must have heard the ghost! In terror, she grabs a gun and shoots at the curtain; with a rip and a crash, his dead body falls forward, and she screams in triumph, “I’ve killed the ghost!” Monica pounds on the bedroom door, demanding to be released; seeing the bloody scene, she runs away screaming for help.

“As the curtain falls,” the composer writes, “Baba kneels over Toby’s lifeless body, desperately seeking the truth in his unanswering eyes.”

— Andrea Lamoreaux

Andrea Lamoreaux is Program Executive at Fine Arts Radio Station WFMT-FM in Chicago.

Album Details

Total Time: 62:05

Recorded: November 12, 16, 17, & 23, 1996 in Bennet-Gordon Hall at Ravinia, Highland Park, Illinois

Producer: James Ginsburg

Co-Executive Producer: Barre Seid

Engineer: Lawrence Rock

Production Assistant: David Dieckmann

Cover: Carol Rosegg

Design: Cheryl A Boncuore

Notes: Andrea Lamoreaux

© 1997 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 034