Store

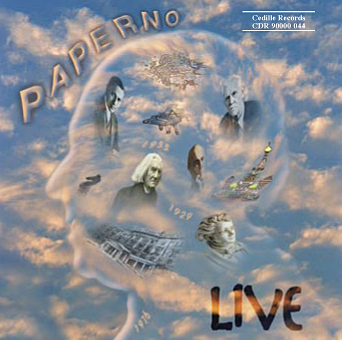

Within a 24-hour period in late 1975, pianist Dmitry Paperno’s distinguished profile in the Soviet music world rose sharply and then disappeared. No sooner had Melodiya, the state record label, released Paperno’s fourth solo album then the Moscow-trained musician notified officials of his intentions to emigrate to the West, effectively ending his two-decade career as a major Soviet concert and recording artist.

This CD comprises what Paperno considers some of his best recordings from his heyday as a Soviet artist. The CD booklet includes excerpts from Paperno’s memoirs, Notes of a Moscow Pianist (Amadeus Press), his firsthand account of the rich musical life, the tensions of international music competition, and the political repression of the Cold War years in Moscow.

The 76-minute disc comprises digital transfers of Melodiya master tapes from 1967 and 1975. Paperno’s 1975 recordings of Brahms’ Rhapsody in G minor, Op. 79, No. 2; Liszt’s Tarantella and Polonaise No. 2 in E major; and Grieg’s Ballade, Op. 24, appeared on his final Melodiya album. An adulatory Fanfare review (September/October 1978) of that LP, available briefly in the US, praised Paperno’s wide interpretive range, carefully controlled dynamics, and “splendidly clean passagework and much subtle rhythmic inflection.” The Liszt Tarantella displays “an intelligence rarely brought to the performance of music by Liszt.” The Brahms Rhapsody is “elegantly shaped and bears much rehearsing.” The Grieg Ballade is “a real achievement.”

“In this particular Romantic repertoire, Paperno’s pianism stands with that of such celebrated Russian pianists as Richter and Gilels,” asserts Cedille Records producer Jim Ginsburg, who has worked with Paperno on four previous CDs. “To Paperno, every note has a role to play in the unfolding drama of the piece,” Ginsburg says. For example, he invites listeners to compare Paperno’s revelatory reading of Liszt’s Rhapsodie Espagnole with Gilels’ on BMG/Melodiya.

Stereo Review‘s Richard Freed, in reviewing Paperno’s first disc on Cedille, was struck by Paperno’s “affectionate conviction” in what he plays and the “touch of poetry” in his playing: “That quality makes itself felt throughout the entire program, in fact, in the least aggressive way: You feel the pianist is really finding it in the music rather than imposing it from the outside,” Freed wrote. CD Review noted, “Paperno avoids the twin traps of overinterpretation and repression of honest expression.”

Born in Kiev in 1929, Paperno studied at the Moscow Conservatory with legendary teacher Alexander Goldenweiser, whose personal contacts included Tchaikovsky, Rimsky-Korsakov, Rachmaninov, Scriabin, and Medtner. Although Paperno performed throughout the Soviet Union and Eastern-bloc countries and made numerous recordings for Melodiya, the introverted, self-effacing pianist was only occasionally permitted to concertize in the West, most notably as soloist with the USSR State Orchestra at Expo in Brussels in 1958. Since emigrating to the US in 1976, Paperno has pursued a characteristically low-profile career as a professor at Chicago’s DePaul University (since 1977), while maintaining a modest concert schedule. In 1989 Cedille Records coaxed Paperno into the recording studio after a long absence, and a new audience began noticing that Paperno is, as the Cleveland Plain Dealer says, “clearly a remarkable pianist.”

Preview Excerpts

JOHANNES BRAHMS (1833-1897)

FRANZ LISZT (1811-1886)

EDVARD GRIEG (1843-1907)

FRANZ LISZT

FREDERIC CHOPIN (1810-1849)

Sonata No. 2 in B-flat minor, Op. 35

FRANZ LISZT

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletRecording Experiences in the Soviet Union

Excerpts from Notes of a Moscow Pianist

Notes by Dmitry Paperno

Since 1955, I had recorded about fifteen hours of music on Melodiya LPs and master tapes for the so-called Golden Fund (that is, preserved forever in the Moscow House of Recording archive). Recording is a special field of performance, which seems at first not to require as much expenditure of nervous energy as a public performance. You may do as many takes as needed to capture a stubborn spot (a group of measures, one passage, whatever) faultlessly, and then an experienced audio engineer will physically splice it into a master tape, which will sound over the air for many years (at least this was the common practice before the digital method revolutionized the editing process in the 1980s).

On the other hand, a recording session requires you to sit at the piano in a huge, empty studio (meaning the Moscow Recording House), “face to face” with the microphones. There is no audience, none of those creative impulses that only a concert hall can provide. And yet the tape should not only be perfect in a technical sense but emotionally bright as well. Sometimes it takes long hours to make the spirit and the letter of the performance conform, its expressiveness and precision, emotions and logic.

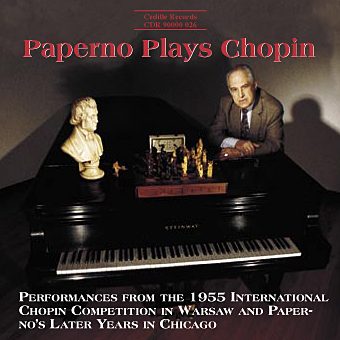

After returning from the 1955 International Chopin Competition in Warsaw, by order of the recently anointed minister of culture, all four Soviet laureates made Chopin recordings. These records quickly sold out and soon became collector’s items. One memorable episode in this connection: in the studio, I learned that I could not play one of the two planned études (Op. 10, No. 8, in F), since Ashkenazy just made a tape of it earlier that day, and our programs were not to coincide. I had practiced for some fifteen minutes while they set the microphones, and decided to try another one — C-sharp minor, No. 4 — from the same opus. It had not even been a part of my competition program, even though I, of course, knew and played it by heart. To our surprise, it went off so dashingly and assertively that it became one of the best pieces on the record (musicians will understand my satisfaction). (The étude in F, as performed during the second stage of the 1955 Competition, was included on my Chopin-live CD — Cedille CDR 90000 026.)

The first several years I preferred to work with the experienced, somewhat conservative Vassily Fedulov (the only sound producer with whom the microphone-phobic Vladimir Sofronitsky felt comfortable). In the summer of 1955, simultaneously with my Chopin LP, the Moscow Recording House commissioned several more pieces, including Liszt’s acrobatically difficult 9th Rhapsody (“The Carnival in Pest”). After the Chopin Competition, I was exhausted, and taping the 10-minute 9th Rhapsody, difficult though it may be, took six nervous hours. Sometime later, Fedulov, having spent nearly twice as long on the complicated process of editing, called me to listen to the tape. Everything seemed clear and correct, but the spirit and life were not there. I felt guilty — so many hours of hard, tedious work had been spent practically in vain — one would not want to present such a tape to the Audio Council. But it was not for nothing that performers loved to work with Fedulov.

“You know what,” he said, “I can see you don’t like the tape. Me too. Let’s try it once again in autumn; and I’ll save this tape, just in case.” I returned to the studio in September; we taped the Rhapsody for three hours and edited for six. The audio council accepted the tape with honors.

In 1958, we were making a second recording with Fedulov, which included the Bach-Busoni Chaconne. Close to midnight, when our time was up and everybody was exhausted, I risked telling him through the mike, “Vassily Vassilievich, give me five more minutes, I want to try the beginning one more time. There is something I still do not like.” Without saying a word, Fedulov sat down heavily at the control panel, and then one of those things happened that makes the performing arts so unpredictable. The same first five pages, which we had re-taped several times due to wrong notes or emotionally flat tones, sounded unexpectedly in one wave, bright, strong, and without the tiniest blot. As soon as I hit a wrong note, I stopped. “Well done,” Fedulov’s voice came over the speaker. “Five minutes ago, it was hard to believe, but it seems now we can use it whole, without editing.”

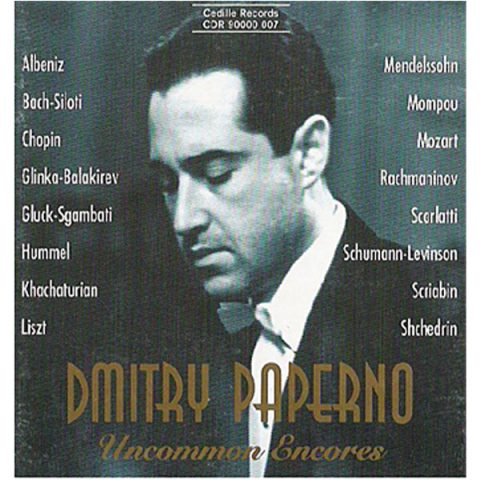

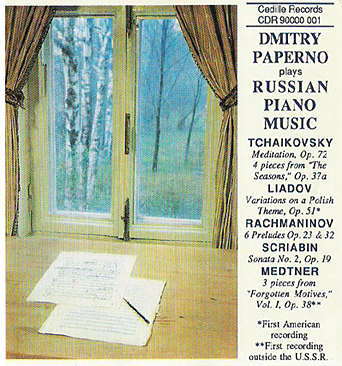

This recording also included two preludes by Debussy and three pieces by Nikolai Medtner from the first book of Forgotten Motives, Op. 38. Soon after its issue, an old friend, a musician and radiologist, Lev Tarassevich, told me that Anna Mikhailovna Medtner, the widow of the great Russian composer and a relative of Lev’s wife, wanted to visit with me. She had recently returned from England to spend her last years in her native Moscow. (Incidentally, Gilel’s authority helped to make her dream come true.) I met the small, active old lady, filled with the memories of her brilliant husband. She made a very flattering compliment regarding my Medtner recording (she liked especially the Danza Silvestra, Op. 38, No. 7, a very refined piece with an unusual rhythmical structure). Later the same evening she offered me the chance to do the Russian premiere of Medtner’s Third Concerto. I asked for some time to think it over and finally turned the offer down several days later, causing some chagrin on her part, and real displeasure to my teacher, Alexander Goldenweiser, who had always loved Medtner’s music dearly. Indeed, my reasons were practical rather than artistic — work on this very long and complicated Concerto would have taken no less than half a year. So, I was wrong again. The Third Concerto was recorded and played a few times by Tatiana Nikolayeva under conductor Evgeny Svetlanov, a 1951 Gneissin graduate from the studio of Maria Gurvich, herself a student of Medtner. (The three Medtner pieces were included on the program of my first CD — Cedille CDR 90000 001.)

One significant event from 1957: my second performance in Tblisi, when for the first time I appeared on stage in a long tailcoat. But another circumstance attached to this concert was much more important and totally unexpected: the great pianist and pedagogue Heinrich Neuhaus, who was visiting friends in Tblisi, attended the concert and came to my dressing room afterward. He was very benevolent (“Really good playing — well done! We don’t hear such a Spanish Rhapsody too often. And your Medtner!”) In a few minutes, not without his help, I managed to compose myself, and he stayed a while, to the delight of those present, talking in his unique, animated manner about music, the stage, composers. Can one forget such an evening?

My biggest disappointment was what happened in the mid-1960s to a recording of the Schumann Humoresque, Op. 20. An excellent audio producer, Yury Kokzhayan, and I had worked on it with great excitement. When we listened to the master tape, it was rewarding to watch the creative, temperamental Kokzhayan enjoying every phrase as his own brainchild (and in many respects, it was so).

While some of my 1950s recordings eventually came to disappoint me and yet were still aired (Beethoven’s Thirty-two Variations, Scriabin’s Waltz Op. 38), the council this time did not approve our Humoresque for the Golden Fund, but only for the so-called limited one. Kokzhayan cursed so sincerely that to watch and listen to him was a comfort. In five years this, the best of my Soviet tapes, was probably demagnetized, according to regulations. My friend, the composer Victor Kouprevich, who was then serving a term in the council, told me with outrage that before the thirty-five minute Humoresque they had listened to some even longer piece, quite monotonous, and part of the panel simply got bored.

Harsh budget cuts throughout the Soviet economy had spread to both the Moscow Recording House and the Melodiya firm. By the beginning of the 1960s the honorarium per audio minute had been cut by two-thirds. To be a recording artist was still honorable, but the remuneration for it now seemed more symbolic than real.

At the end of the 1960s, Moscow Radio commissioned several performers to make master tapes of light instrumental pieces (no longer than two minutes at most) to fill in pauses on the “Lighthouse” channel. I was offered an interesting task, one that was not as simple as it may sound — twelve études of Czerny (from Opus 740) and Moszkowski. In my school years, before switching to Chopin’s études, I had played them often and, to Goldenweiser’s satisfaction, quite dashingly. Coming back to these pieces after a twenty-five-year break, I spent a lot of time and effort to make them not only masterly but more imaginative, for all their unassuming nature. The simple and salutary music of Carl Czerny — a student of Beethoven and teacher of Liszt — captures the essence of classical piano technique and should continue to benefit many generations of pianists. This unusual tape was also accepted by the audio council with honors.

In the winter of 1975, I made my last Soviet record, which included Grieg’s Ballade, Op. 24, Liszt’s Polonaise in E and Tarantella, and Brahms’s Rhapsody, Op. 79, No. 2. (Chopin’s Sonata No. 2 and Liszt’s Spanish Rhapsody were on my previous Melodiya LP, released in 1967.) Soviet emigration was in its first wave in 1975, and every application handed in by a more-or-less known figure in Moscow immediately became a sensation. The initial shock of disbelief gave way to a wide spectrum of reactions. But not among the authorities — Homo sovieticus remained true to himself. The applicant immediately became a traitor and was treated accordingly, less obviously by the big shots, and worst of all by small fry of every kind. We decided to hand in our application immediately after my last Melodiya recording was issued (so as not to jeopardize its release). On the evening of November 15, the scheduled day of my recording’s sale, we checked the record store next to the Conservatory, having decided that tomorrow, no matter what, I would inform Mosconcert of my decision — highly unpleasant news for them. The record went on sale earlier the same day…

NOTES ON THE PROGRAM

Brahms: Rhapsody in G minor, Op. 79, No. 2

In contrast to the brightly expressive folk genre of Liszt’s famous Hungarian and Spanish Rhapsodies, the piano rhapsodies of Brahms are closer in their somber spirit to the German romantic ballades of the 18th century.

The influence of Schumann, with whom the life and creative work of Brahms was closely connected, is obvious in the G-minor Rhapsody. The texture and rhythmic pulse of the Rhapsody are reminiscent of the first piece from Schumann’s Kreisleriana. Images of tense dramatic action come in contraposition to lyrical yet emotional episodes. The overall color of this music is gloomy and severe.

In the coda, Brahms gives a brilliant example of a “100 percent natural” slowing down; that is, without indication in words (like ritenuto, piu sostenuto, etc.), but only by the gradually changing durations of the notes. This “device” is relatively rarely used (the first case known to me is the transition from stormy middle section to serene recapitulation in the slow movement of Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 20 in D minor). The execution of these four measures of “(quasi rit.)” (as Brahms tactfully marks it in the score) should be strictly precise. The two last chords — ff — make a strong final command.

Liszt: Polonaise No. 2 in E major

Almost forgotten by pianists today, the Polonaise No. 2 (1851) is now heard more often in Liszt’s own orchestral version. During the 19th century, though, it used to be part of the regular concert repertoire of Busoni and Rachmaninov. The piece is typical of Liszt’s large scale “theater” works: noble, proud and descriptive, full of action. Liszt’s inexhaustible creativity truly amazes here. The listener always perceives the generous variety of pianistic textures presented. Particularly striking is the approach and beginning of the almost dreamy recapitulation, where the filigree passages in the right hand attach the twinkling rings of many little bells to this “reminiscence of Polonaise.” In this case, as well as with the first Mephisto Waltz or Tarantella, it does not seem to matter which was created first — the orchestral or piano version. In fact, those who have heard first these great piano pieces with their rich variety of colors, texture, and overall brilliance, might well prefer them forever (at least this is my personal experience).

Grieg: Ballade in G minor, Op. 24

The Ballade, Op. 24, is one of Grieg’s most significant works for piano. It was created, in Grieg’s own words, “in days of despair and mourning,” in 1875, soon after he lost both parents. The piece is a big, lyrical-epic canvas, embodied in variation form. Grieg’s diverse transformations of the original, simple Norwegian folk melody render the tune at times almost unrecognizable.

The Ballade intersperses lyrical, melancholic reflections with variations spanning a wide variety of moods, including a strongly rhythmic Halling (Norwegian folk dance). As the work progresses, a “funeral march” and triumphal culmination are suddenly overcome by a stormy tragic coda marked allegro furioso. The beautiful return of the unchanged, original sad melody frames the big-scale picture with a touch of eternity as no words could.

The rather unusual, almost elusive form of the Ballade requires special attention from both performer and listener. The whole piece sounds like an inspired improvisation.

The harmonic language of the Ballade is highly distinct and sounds fresh even today. In my lectures on the role of harmony in piano performance, I never miss an opportunity to invite the audiences to enjoy the beauty and creativity of Grieg’s harmonization of the simple four-part texture of the opening.

Liszt: Tarantella from Venezia e Napoli

Not much needs to be said about the Tarantella from the appendix to the 2nd book of the Années de pèlerinage (Venice and Naples). In this bright picture of a folk festival, Liszt used actual Neapolitan tarantellas and a “Canzona Napolitana” as well. It is worth mentioning the clarity of the well-proportioned big-concept and form, and the variety of piano techniques represented. Note the chain of variations in the Canzona (the middle section): a non-stop fountain of creativity. The fiery, joyful finale is also captivating. It’s interesting that in the Tarantella, Liszt freely uses the repeated-note technique that only began to flourish some 30 years later, after piano makers designed and implemented into their instruments so-called “double action.” By the way, in his last years the great musician was presented with this new type of piano by Bechstein as a token of admiration. (I had the enormous privilege to practice on it in Liszt’s house in Weimar in 1961.)

Chopin: Sonata No. 2 in B-flat minor, Op. 35

Chopin used the Polish word “zal” (pronounced “zhal” — “sorrow” is the closest English translation) to describe the emotional substance of his music. Liszt defined it as “an inconsolable mourning over an irreparable loss.” These words could apply wholly to the Sonata No. 2, Op. 35, in which the scope of human suffering is expressed with staggering force. Both its musical images and means of expression appeared so new and uncommon for Chopin’s contemporaries that even great musicians, including Chopin’s friends, were critical. Schumann call the sonata a “Sphinx,” and declared, “it is hardly a sonata but rather his four most unruly children whom he has put together.”

Chopin left no comments on this greatest of his works, except for a passing remark about its unusual Finale: “the right and the left hands play in unison, chattering with each other after the march.” Anton Rubinstein put it differently in his well-known aphorism: “A wind howling over the graves.” This poetic description points out for the first time the integrity of Chopin’s tragic work. (It is interesting that Chopin composed the Funeral March — the focal point of the whole concept — several years before he wrote the rest of the Sonata, which he finished in 1839.) The great Russian musician was virtually the first to comprehend fully the magnitude of the sonata and initiated its enormous popularity.

Liszt: Rhapsodie Espagnole

We finish the disc with Liszt again, and one of the most brilliant piano pieces ever written. One may say that, with the exception of double notes, the Spanish Rhapsody incorporates virtually every kind of piano technique. (It’s worth pointing out at least one of Liszt’s novelties in fingering, namely the 1-5 pattern in the series of ascending scales at the end of the Jota section.) Liszt wrote it during his last Roman period in the 1860s. The Rhapsody is based on two Spanish folk melodies, Jota (from Aragon) and the equally popular La Folia, which until recently had been attributed to Corelli. Liszt’s mastery of variational development reaches its highest level here. At the end, the fiery and pianistically very effective culmination of the Jota turns spontaneously into an exultant last transformation of La Folia, hardly recognizable in this hymn of life and rejoicing.

— Dmitry Paperno

Dmitry Paperno’s Notes of a Moscow Pianist is available from Amadeus Press (800-327-5680).

Album Details

Total Time: 76:00

Recorded: Material under license from Melodiya, Moscow

Producer: James Ginsburg

Remastering Engineer: Konrad Strauss

Cover photo: Paperno in the Moscow Conservatory

Design: Cheryl A Boncuore

Notes: Dmitry Paperno

© 1998 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 037