Store

On Haydn & Mysliveček Cello Concertos, American cellist Wendy Warner, a protégé of Mstislav Rostropovich, and Camerata Chicago, conducted by its British-born founder, Drostan Hall, present Franz Joesph Haydn’s essential C Major and D Major Cello Concertos, harmoniously paired with a genuine rarity: the C Major Cello Concerto of Czech composer Josef Mysliveček (1737–1781), a Haydn contemporary.

Preview Excerpts

FRANZ JOSEPH HAYDN (1732–1809)

Cello Concerto in C major

JOSEF MYSLIVEČEK (1737–1781)

Cello Concerto in C major

FRANZ JOSEPH HAYDN (1732–1809)

Cello Concerto in D major

Artists

7: Cadenza: Emanuel Feuermann

8: Cadenza: Maurice Gendron

Program Notes

Download Album BookletHaydn and Myslivecek Cello Concertos

Notes by Andrea Lamoreaux

Were it not for the extraordinary individual musical genius of a few in 18th century Europe — Bach, Handel, Haydn, Mozart — we might better remember and admire the myriad of other composers who were active during the periods musicologists identify as the High Baroque and Classical eras. In the 20th century, musicians revived interest in two composers from the earlier period: Georg Philipp Telemann and Antonio Vivaldi. These had not been completely forgotten but their music was performed very infrequently compared to their celebrated colleagues’ masterpieces.

There’s lots more rediscovery still to do, especially within the Classical period. One can only hope that the quality of Joseph Mysliveček’s C major Cello Concerto, revealed on this CD, will encourage further investigation of this composer’s prolific output. Born in Prague in 1737, Mysliveček was successful and widely admired during his brief lifetime. In some ways, he’s a forerunner of Mozart, whom he met and befriended in 1770. Mysliveček emigrated from Prague to Venice in 1763 to study composition. He rarely left Italy after that, producing a string of operas that were successfully produced at numerous Italian theaters, including the famous Teatro San Carlo in Naples. Along the way, Mysliveček also wrote symphonies, concertos, chamber music for winds and strings, oratorios, and solo sonatas.

Mozart rearranged an aria from one of Mysliveček’s few failures, the opera Armida, as the concert aria “Ridente la Calma” (K. 152), which remains a favorite of singers and audiences today.

Both Mozarts — father and son — admired Mysliveček, but he and Wolfgang parted company in the late 1770s, apparently because Mysliveček failed to fulfill a promise to get Mozart an opera commission from the Teatro San Carlo. By this time, the composer known in Italy as Il Boemo (The Bohemian) was ill and poverty-stricken. He died in Rome in 1781, a month shy of his 44th birthday.

Before his falling-out with Mozart, Mysliveček was one of the most successful opera composers in Europe. Mozart would struggle for years to achieve similar operatic success. Today, of course, Mozart’s operas are among the most loved and performed, while Mysliveček’s have been completely forgotten. Unfortunately for Il Boemo’s legacy, his music dramas all stayed firmly within the realm of the old-fashioned opera seria, with fancy arias and static plots, while Mozart branched out into newer styles and created human rather than mythological characters.

Most of Mysliveček’s surviving concertos are for the violin. The Cello Concerto in C is an arrangement of a violin concerto. Mysliveček also wrote concertos for flute, keyboard, and wind quintet.

The Cello Concerto is scored for two oboes, two horns, and strings. The Allegro moderato opening movement, which conspicuously delays the entrance of the soloist, follows sonata form in its modulation from C major to the relative G major and back again. The themes and their development are characterized by syncopation, displaced accents, and several touches of chromaticism, plus wide interval leaps — octaves and tenths — that recall melodic lines from some of Mozart’s opera arias. Cast basically in 4/4 time, the movement often features a contrasting triplet rhythmic pattern. The solo part is virtuosic, with a notably high range. The recapitulation is highlighted by an elaborate solo cadenza.

The central movement, marked Grave, has the soloist accompanied by strings alone. Alternately plaintive and intense, it emphasizes the chromaticism that was occasionally heard in the Allegro. The ending is quiet and serene. Cheerfulness characterizes the finale, which is marked Tempo di minuetto and, as with many other 18th-century concertos, proceeds in the manner of a rondo. Again the virtuosic solo part is often placed in a very high range, giving the work special brilliance as it moves toward its close.

When Bach worked for the princely court in the small German town of Cothen, he found that his music-loving patron employed an orchestra of highly skilled players. Bach composed for these a number of solo concertos, challenging instrumental suites, and (in spite of their name) the Brandenburg Concertos. A generation or so later, Haydn discovered the same thing when he accepted a job as composer and orchestra leader for Prince Esterhazy. Although this Hungarian native lived far from the central European musical capital of Vienna, he brought to his country estate an instrumental ensemble full of virtuosos. Over his many years with the Esterhazy family, Haydn wrote numerous concertos for these players. One that was rediscovered only in the 1960s is a Concerto in C major written for the Esterhazy orchestra’s principal cellist, Josef Weigl, who was apparently a performer of truly uncommon skill. Haydn scholar H.C. Robbins Landon notes that Haydn wrote the cello solos in many of his symphonies with Weigl in mind. The C major concerto dates from the early 1760s.

The scoring in both of Haydn’s cello concertos is identical to that of Mysliveček’s: two oboes, two horns, and strings. Both of Haydn’s are also in the standard three movements. Haydn’s C major Concerto was first performed at the Prague Spring Festival of 1962. János Starker gave the U.S. premiere at Carnegie Hall in 1964. Mr. Starker rated the concerto “among the purest music Haydn ever wrote.” It’s also a tremendous challenge and triumph for the soloist. Some scholars have claimed that Haydn disliked virtuosic display. His popular Trumpet Concerto, however, suggests otherwise. This early cello concerto is, likewise, a virtuoso romp. The opening movement is marked Moderato. It unfolds more in the manner of a Baroque concerto than a Classical-era one, with alternations between soloist and orchestra, tossing the main theme and its variants back and forth. Also reminiscent of the Baroque are its frequent dotted rhythms. An intricate solo passage mid-movement fore-shadows the fancy finger-work to come in the finale.

The Adagio has the feel of an instrumental aria. It’s in F major and the accompaniment is strings only. The soloist enters on a long, sustained note. This lyrical, virtually monothematic movement serves as a serene interlude before the Allegro molto finale, where the soloist really takes off. The full orchestra is employed once again, but the spotlight is on the solo cello. The finale’s rapid pace is emphasized by the soloist’s frequent run passages, which often scale the instrument’s highest range. The basic key has returned to C major, but with many sudden departures into the minor mode for contrast. Cheerful and dramatic at the same time, it provides a sizzling conclusion to this happy rediscovery.

By the 1780s, composer-performer Anton Kraft was leading the Esterhazy orchestra’s cello section. For some time he was believed to be the real author of Haydn’s Cello Concerto No. 2 in D major. That claim was refuted when Haydn’s original score was uncovered in the 1950s, but it’s entirely possible that Haydn consulted with Kraft on some details of the solo part. Once again the solo part is virtuosic, though emphasizing expressiveness more than sheer brilliance.

Haydn casts the opening Allegro moderato in the standard Classical sonata form he established so firmly with his symphonies. This opening movement is considerably longer than the other two combined, often characterized by a thoroughly symphonic integration of the solo part and orchestral texture, although the soloist still has opportunities to stand out. An Adagio in A-B-A’ form, the second movement is in the closely related key of A major. The orchestral scoring is for strings and oboes (no horns). The expressiveness and melodic beauty of Haydn’s writing is especially evident in Wendy Warner’s lyrical performance. The horns return for the rollicking D major finale, cast in 6/8 time with definite suggestions of folk music. It’s structured as a rondo and modulates freely through a number of keys, including F major, plus a striking section in its relative D minor that contrasts strongly with the generally cheerful and outgoing nature of the rest of the work.

Scholars believe Haydn wrote many more solo concertos for the Esterhazy players that have been lost. Cellists and all music lovers are fortunate we have these two.

Andrea Lamoreaux is music director of 98.7WFMT, Chicago’s classical experience.

Album Details

Total Time: 73:05

Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineer: Bill Maylone

Recorded: November 26–29, 2012, in College Church, Wheaton, Illinois

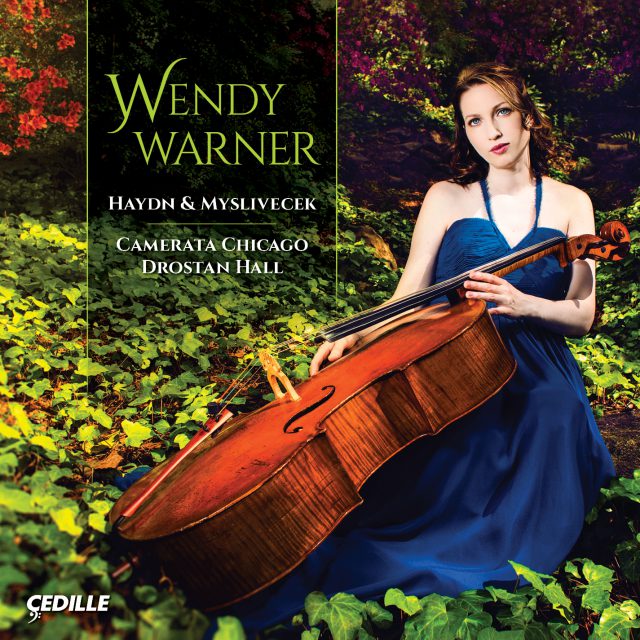

Cover Photo: Sammie Saxon Photography

Cover Design: Sue Cottrill

Inside Booklet and Inlay Card: Nancy Bieschke

Cello: Giuseppe Gagliano 1772

Cello Bow: François Xavier Tourte, c.1815, the “De Lamare” on extended loan through the Stradivari Society of Chicago

© 2013 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 142