Store

Trio Settecento, the “superlative Chicago-based early music ensemble” (Gramophone) completes its geographical grand tour of the European Baroque with An English Fancy, its highly anticipated survey of English Baroque chamber works. It’s the final leg of a musical journey that has delighted record collectors and critics alike. Previous installments include An Italian Sojourn, A German Bouquet, and A French Soirée.

On An English Fancy, trio members Rachel Barton Pine, violin; John Mark Rozendaal, viola da gamba; and David Schrader, harpsichord and positiv organ, focus on the fantasy, the form that infatuated English Baroque composers.

Listeners will venture into unusual realms of sonic imagination by virtue of the daring experiments in melody, harmony, counterpoint, and other musical elements heard in these 16th- and 17th-century works.

English folk tunes infuse many of the pieces. The CD opens with Trio Settecento’s own adaptation of William Byrd’s nine keyboard solo variations on “Sellenger’s Rownde.” It closes with the trio’s variations on Henry Purcell’s “Hole-in-the-Wall.”

Preview Excerpts

WILLIAM BYRD (1539–1623)

TOBIAS HUME (ca. 1569–1645)

WILLIAM LAWES (1605–1645)

JOHN JENKINS (1592–1678)

Suite in G Minor

CHRISTOPHER SIMPSON (d. 1669)

"The Little Consort," Suite in G Minor/Major

THOMAS BALTZAR (c. 1631–1663)

MATTHEW LOCKE (ca. 1621–1677)

"For Several Friends," Suite in B-flat

HENRY PURCELL (1659–1695)

Ayres, Compos’d for the Theatre

Artists

28: PURCELL

29: PURCELL

Program Notes

Download Album BookletAn English Fancy

Notes by John Mark Rozendaal

The most principal and chiefest kind of music which is made without a ditty is the Fantasy, that is when a musician taketh a point at his pleasure and wresteth and turneth it as he list, making either much or little of it according as shall seem best to his own conceit. In this may more art be shown than in any other music because the composer is tied to nothing, but may add, diminish, and alter at his pleasure. And this kind will bear any allowances whatsoever tolerable in other music except changing the air and leaving the key, which in Fantasie may never be suffered. Other things you may use at your pleasure, as bindings with discords, quick motions, slow motions, Proportions, and what you list. Likewise this kind of music is, with them who practise instruments of parts, in the greatest use, but for voices it is but seldom used.

— Thomas Morley

from A Plaine and Easier Introduction

to Practicall Musicke, London, 1597.

Of Musick design’d for Instruments . . . the chief and most excellent, for Art and Contrivance are Fancies, of 6, 5, 4, and 3 parts, intended for Viols. In this sort of Musick the Composer (being not limited to words) doth employ all his Art and Invention about the bringing in and carrying on of . . .

Fuges, according to the Order and Method formerly shewed. When he has tried all the several wayes which he thinks fit to be used therein; he takes some other point, and does the like with it; or else, for variety, introduces some Chromatick Notes, with Bindings and Intermixtures of Discords; or, falls into some lighter humour like a Madrigal, or what else his own fancy shall lead him to; but still concluding with something that hath Art and excellency in it.

— Christopher Simpson

from The Division Viol, London, 1659.

All European nations developed musical genres with the name (in one form or another) “fantasy.” But only the country that gave the world William Blake, Lewis Carroll, and Monty Python — only the English — had the extravagant turn of mind to adopt the Fantasy as its primary vehicle for instrumental chamber music for a full century. English composers of the 16th and 17th centuries gave wing to their flights of fantasy with daring experiments in musical form, melody, harmony, counterpoint, decoration, instrumental techniques, gestures, colors, combinations, and even spiritual exploration. Trio Settecento’s recital of English music includes forays into all of these realms of sonic imagination.

A feature of this repertoire is the prominent role of the viola da gamba. At the turn of the 17th century, the lute was giving way to the viola da gamba as the preeminent vehicle for stringed-instrument virtuosity in England; the viol (as the English economically refer to it) held that status until the Restoration, when new continental styles of violin playing came to Britain. Five of the composers represented here were themselves virtuoso viol players, renowned in their day for their performing as much as for their compositions. Solo performers on the bass viol in England developed two distinct modes of execution. The “lyra viol” and the “divisions viol” seem not to have been two different musical instruments (although a particular viol may be designed to suit one idiom better than the other) but two ways of performing on and composing for the viol. In playing “divisions” the violist takes a tune or bass line written in slow note values and creates variations by dividing those long notes into smaller, faster ones. Henry Butler developed the technique to a pinnacle of virtuosity in which those very long notes may be rendered as lyric melody, glittering cascades of scales, leaping and turning figures, or tortured passages of simulated counterpoint exploiting the instrument’s entire four-octave range.

The lyra viol, on the other hand, was a viol played in the manner of a bowed lute. Lyra viol repertoire is notated in lute tablature, a sort of graphic notation that facilitates writing and reading of dense or airy chordal textures in a variety of tunings. Tobias Hume, William Lawes, John Jenkins, and Christopher Simpson all used both manners of writing for the viol. In the works presented here, we find these virtuosi exploring a variety of approaches to integrating these specific instrumental idioms into ensemble textures.

One time-honored format for expression of a musician’s fancy is variations on a theme. Britain’s vast repertoire of traditional tunes for ballads and dances provided a rich source of material, including many melodies whose beauty led to sustained popularity both at home and abroad. William Byrd seems to have had a special love for this music, for traditional tunes frequently appear embedded in various ways in his solo keyboard and chamber music. In such works, one hears a brilliant composer of art music both receiving inspiration from and paying tribute to his nation’s native lyric genius. Trio Settecento has adapted Byrd’s nine solo keyboard variations on Sellinger’s Rownde for ensemble performance.

The remarkable composition, Captaine Hume’s Lamentation, is found in the 1605 print Captaine Hume’s Musicall Humors, dedicated to King James I. Tobias Hume was the model for the character of Sir Toby Belch in Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night. Like Sir Toby, Tobias was a mercenary soldier gone to seed at court. Sir Toby also mentions his admiration for Sir Andrew’s playing on the “viol de gamboys.” The biggest giveaway, however, is Shakespeare’s pun on the name of Hume’s book, Captaine Hume’s Musicall Humors, so titled to indicate the rich variety of moods in the music. Hume’s use of the word humors refers to the renaissance conceit that human emotions result from the balancing of four fluids in our bodies: blood (for the sanguine mood); black bile (melancholy); yellow bile (choler); and phlegm (self-explanatory). Thus the pun: Hume – humor – bodily fluid – Belch. Buffoon though he may have been, Hume was capable of writing deeply serious music, including a meditation on “Deth,” [sic] several profound pavans, and a heart-wrenching portrait of the ill-fated Lady Arabella Stuart. Captaine Hume’s Lamentation is unique in several respects. Composed for a lyra viol in “normal” tuning accompanied by a single, unspecified treble instrument, the seven-minute piece is a through-composed emotional odyssey trans-porting performers and listeners through regions of grief, despair, rapture, tranquility, and mystery. This is music worthy of the age that gave us Shakespeare.

The term fantasy suite has been coined to describe a genre invented by Giovanni Coprario (aka John Cooper, the Italian-trained dean of English composers who tutored William Lawes and Prince Charles (later King Charles I) in music and mentored a generation of English composers). The form consists of a fantasy followed by a pair of dances scored for two or three instruments (combinations of bass viols and treble instruments) accompanied by elaborate obbligato organ parts. Often the second dance is completed or followed by a slow section referring back to the opening fantasy. These perorations make it clear that the pieces are not just collections of individual movements but truly integrated multi-movement works. These were the first such works ever composed — created decades before the Italian sonata and French dance suite achieved a similar balance of articulation and integration. Coprario’s suites are of such simplicity that one can easily imagine the prince playing the bass viol parts himself, as legend has it he did. The fantasy suites of Lawes and John Jenkins are another matter, featuring brilliant virtuoso passagework for all instruments.

The wonderfully strange and passion-ate sound world of William Lawes defies description. Lawes’s fantasia sets for four, five, and six viols have achieved cult status due to their remarkable combination of musical beauty, emotional intensity, and sheer weirdness. These qualities are likewise present in his works for smaller ensembles.

In the Almaine, subtitled “la goutte,” the instrumental delivery of a single tone is a musical event capable of development by imitation, repetition, extension, sequence, stretto, and so on, creating a sort of proto-minimalism.

If Lawes was the Mozart of his day in England, John Jenkins was the corresponding Haydn figure for that time and place. Like Haydn, Jenkins worked mainly in the country homes of music-loving aristocrats and produced, throughout a long career, a steady stream of innovative work characterized by wit, infinite melodic invention, craftsmanship, and generous good nature. Also like Haydn, Jenkins seems to have been content to watch his younger, more romantic colleague shine in the more brilliant and dangerous orbit of the court. Where Lawes’s music continuously flirts with contrapuntal and affective disaster, involving performers and listeners in a sort of musico-emotional brinksmanship, Jenkins’s art depicts strong passions and serene pleasures with unfailing aplomb. In the Suite in G Minor, Jenkins gives extra scope to his fancy by writing out the repeats of his dances with elaborate, transformative ornamentation. These differences notwithstanding, the music of Jenkins and Lawes (again, like that of Haydn and Mozart) gives evidence of a fruitful dialogue wherein the two composers traded inspirations as they explored different possible realizations of a set of musical genres.

While Christopher Simpson is best remembered for his works for the divisions viol, he also composed music for the lyra viol. The suites in Simpson’s collection The Little Consort are scored for treble viol or violin, lyra viol, and basso. Here the lyra viol contributes modestly to the filling out of the harmony, but its main function is that of a second melodic instrument in dialogue with the violin, creating a true trio-sonata texture.

We have chosen movements from Simpson’s lengthy suites in G minor and G major to create a more condensed set, taking a cue from the tendency of Lawes, Simpson, and Locke to group more or less closely related sets in minor/major key pairings. The suite opens with a pavan. Thomas Morley, directly after his description of the fantasy quoted at the start of these notes, tells us that, “The next [kind of music] in goodness and grace unto this is called the Pavan.” In Morley’s time, the pavan had evolved from a straightforward court processional into an imposing vehicle for carrying substantial and complex emotional material. In the consort sets of Simpson and Matthew Locke, a briefer, lighter type of pavan appears, relying less on harmonic drama and more on melodic gesture, and sometimes taking the honored position usually reserved for the fantasy, at the opening of a set.

The Lübeck-born violinist Thomas Baltzar’s advent on England’s musical scene in 1655 was a sensation colorfully recorded by diarist John Evelyn and music chronicler Anthony Wood. Evelyn heard Baltzar at the London house of Nicholas L’Estrange and relates that he “plaid on that single Instrument a full Consort, so as the rest, flung-downe their Instruments, as acknowledging a victory.” Wood describes a musical meeting in Oxford at which Baltzar

[P]layed to the wonder of all the auditory; and exercising his finger upon the instrument several wayes to the utmost of his power. Wilson, thereupon, the public professor, the greatest judge of Musick that ever was, did, after his humoursome way, stoop down to Baltzar’s feet, to see whether or not he had a huff on, that is to say, to see whether he was a devil or not, because he acted beyond the parts of a man.

Baltzar’s famous multi-stopping and agility in passage work are in evidence in the exciting variations on “John Come Kiss Me Now,” published in John Playford’s The Division Violin of 1684. Not in evidence here or in any surviving work of Baltzar is his use of high positions, remarkable and remarked upon in his day. In recognition of Baltzar’s pioneering achievement, Rachel Barton Pine has adapted this piece to include passages up to the seventh position.

In his later years, Matthew Locke, the finest English composer of his generation, revised his important corpus of chamber music and copied it into a fair manuscript now housed at the British Library. The book contains six groups of suites, each for a different scoring. The works for treble and bass in the group charmingly titled For Several Friends are prime examples of Locke’s genius for leading the listener through a refined series of affective states using only a small number of miraculously entwined melodic voices (two here, never more than four).

Between 1680 and 1695, Henry Purcell composed music for more than 50 theatrical productions — a flood of lyric inspiration comparable to the achievements of Mozart or Gershwin. In this music, Purcell grafts his native melodic gift and mastery of classic English counterpoint onto French overture and dance forms and Italian vocal styles. The result is music whose immediate attractiveness, enduring freshness, and satisfying complexity have never been surpassed in the history of English music. Like all popular theater music, Purcell’s show tunes were immediately adapted and published for domestic use. We have drawn our suite from the 1697 publication A Collection of Ayres, Compos’d for the Theatre, and Upon Other Occasions, freely arranging for our own combination of instruments.

Transcriptions of theater music for performance as keyboard solos were as popular in the 17th century as they are now. Following this practice, David Schrader has made his own arrangement of the Overture from Bonduca for this program. Listeners will certainly notice the harsh dissonances that occur when this piece is performed on a keyboard tuned in a mean-tone tuning. This effect is intentional. The keyboard repertoire of the period exploits the variety of sounds available in these tunings to intensify expressions of desire and anguish on the one hand, and fulfillment and repose on the other when the shrill clashes yield to purest harmony.

Purcell’s Pavan in B-flat Major is one of a group of four pavans scored for two violins, bass viol, and organ, an archaic scoring recalling the fantasia suites of Jenkins and Lawes. Here, however, the ostentatious busy-ness of the cavalier virtuosi is replaced by a more modern, simple, and poignant flow of melodic gesture.

Our program ends as it began, with variations on a beloved English tune. Purcell’s music for the 1695 revival of Aphra Behn’s 1676 play, Abdelazer, contains two hornpipes. One appears in the 1698 edition of John Playford’s collection, The English Dancing Master, under the title “Hole in the Wall,” and achieved lasting fame in country dance circles under that name. (The other hornpipe for Abdelazer is Purcell’s most famous tune, thanks to Benjamin Britten’s The Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra.) The variations on “Hole in the Wall” heard here are our own, fashioned following the instructions of Christopher Simpson in his 1659 book, The Division Viol.

A note on performance practice:

The question of pitch — whether musicians choose to tune their instruments starting at A=440, or A=415, or some other standard — is a vexed one that historically minded performers prefer to consider with care and an open mind. Trio Settecento usually performs at A=415, a pitch close to some of the common standards recorded in the Europe in the 18th century. The trio has performed and recorded French music at A=392, a low pitch known to have been used in France, and one that produced the sweet sound sought in the style précieuse. For this recording we have chosen to play at A=440, a higher pitch than usual for us. Evidence suggests that music may have been performed at this pitch (or possibly even as high as A=460) in early 17th-century England. What is certain is that string players of the period were instructed to tune their highest strings as high (i.e., as tight) as possible without breaking. (It is possible to tell before the string actually breaks.) This high tension produces a quick response and brilliant sound ideal for the quickly running and leaping passage work found in this repertoire. So for this project we have adopted what is for us a high, if not string-breaking, pitch level, not out of a slavish devotion to authenticity but simply attending to the advice of our forebears in our attempt to best serve the music.

An additional track, Henry Butler’s (d. 1652) Sonata in F, is available as a download on iTunes. Henry Butler was a viol virtuoso who spent his career at the court of Philip IV of Spain. According to James Wadsworth, author of The English Spanish Pilgrim (1629), Butler “teacheth his Catholike Majesty to play on the Violl, a man very fantasticall, but one who hath his pension truly paid for his fingers sake.” To perform what he wrote, Butler must have been “fantasticall” indeed, and the pension earned by those fingers should have been a very good one.

Album Details

Total Time: 79:50

Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineer: Bill Maylone

Editing: Jeanne Velonis

Technical Editing: Bill Maylone

Graphic Design: Nancy Bieschke

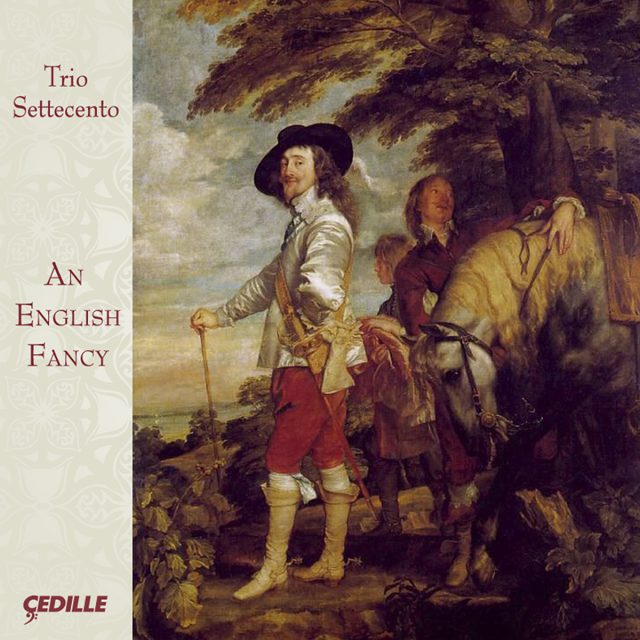

Cover Painting: King Charles I of England Out Hunting, c.1635 (oil on canvas),

Sir Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641) / Louvre, Paris, France / Giraudon / The Bridgeman Art Library

Recorded: August 1–5, 2011, in Nichols Concert Hall at the Music Institute of Chicago, Evanston, Illinois

Instruments:

Violin: Jason Viseltear, 1999, renaissance treble violin based on models of Gasparo da Salò (1542–1609), generously loaned by David Douglass.

Violin Strings: Natural gut by Daniel Larson at Gamut Music, Inc.

Violin Bow: Harry Grabenstein, replica of early 17th Century model.

Bass Viola da Gamba: William Turner, London, 1650.

Harpsichord: Willard Martin, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, 1997. Single-manual instrument after a concept by Marin Mersenne (1617), strung throughout in brass wire with a range of GG-d3.

Positiv Organ: James Louder, Montreal, 2009. Five stops.

©2012 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 135