Store

Store

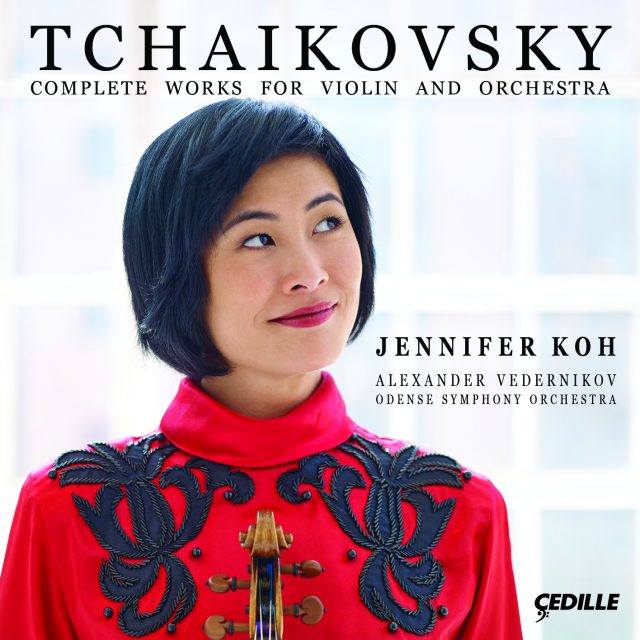

Tchaikovsky: Complete Works for Violin and Orchestra

Alexander Vedernikov, Odense Symphony Orchestra

Jennifer Koh, Musical America’s 2016 Instrumentalist of the Year, headlines an album of Tchaikovsky’s complete works for violin and orchestra. It’s the “remarkable . . . thoughtful and vibrant” (Strings Magazine) American violinist’s first recording of music by Tchaikovsky, who has figured prominently in her rise to the top ranks of violinists worldwide. Tchaikovsky’s Concerto in D Major is one of the most celebrated and daunting works in the violin repertoire. The subdued Sérénade mélancolique illustrates the composer’s ear for orchestral color. The delicate Valse-Scherzo melds old-fashioned elegance with spirited playfulness. Souvenir d’un lieu cher’s poignant, nostalgic mood gives way to a delightful finale.

Koh shared the top prize in the 1994 Tchaikovsky International Competition in Moscow, where she played the Tchaikovsky (and Brahms) concerto and won three special prizes, including for the best performance of Tchaikovsky’s work. The star violinist has a long history with her album collaborators, Denmark’s Odense Symphony Orchestra and its chief conductor, Alexander Vedernikov. In recent years, audiences have heard Koh perform the Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto with the Munich Philharmonic under Lorin Maazel, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra under Carlos Miguel Prieto, Japan’s NHK Symphony under Vedernikov, and the Odense Symphony Orchestra under Christoph Poppen.

Listen to Steve Robinson’s interview

with Jennifer Koh on Cedille’s

Classical Chicago Podcast

Preview Excerpts

Piotr Illych Tchaikovsky

Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 35

Souvenir d’un lieu cher, Op. 42

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletTchaikovsky: Works for Violin and Orchestra

Notes by Patrick Castillo

Tchaikovsky’s music for violin and orchestra spans just three years of his prolific career. Yet in both substance and circumstance, these few works capture an essential part of the composer’s vita. Certainly, they contain the hallmarks of Tchaikovsky’s language — above all, melodic and dramatic instincts that shake the listener to the core — that have enshrined him among the repertoire’s most cherished voices (and, among his countrymen, as the most revered composer bar none). They moreover nod to various important figures in his life and chronicle a period marked by personal turmoil and artistic triumph.

Tchaikovsky’s first essay for violin and orchestra, the Sérénade mélancolique in B minor, Op. 26, dates from early 1875. The work was intended for Leopold Auer, whose later criticism of the Violin Concerto stung the composer and cost Auer the Concerto’s dedication. This went instead to Adolph Brodsky, who premiered both works. The Sérénade manifests Tchaikovsky’s melodic gift not in soaring lyricism, but in pithy stoicism. The soloist’s tearful first utterances, played on the dark-hued fourth string, chasten the deceptively idyllic introduction. Even as the music quickens and delves into a major key, its melodic profile remains tautly contained; the prevailing melancholia precludes any indulgence in rhapsodic flow (as we encounter later in the Concerto). On the reprise of the opening section, a quiet oscillating patter in the flutes, like a wispy gauze surrounding the melody, illustrates Tchaikovsky’s ear for orchestral color, an under-recognized facet of his artistry.

The Sérénade marked the end of Tchaikovsky’s first decade in Moscow, where he had taken up a position at the newly opened Conservatory following his studies in St. Petersburg. This was a formative period, during which he became a prominent figure among Moscow’s cultural elite, rubbing shoulders with the literati and other sophisticates.

As he gained in social celebrity, his horror at the prospect of public gossip about his sexual inclinations intensified. In 1877, Tchaikovsky married Antonina Milyukova, “a woman with whom I am not the least in love” (and, according to his brother Modest, “a crazed half-wit” to boot). The couple separated after two torturous months, though never divorced. Later that year, Tchaikovsky began his curious relationship with Nadezhda von Meck, the eccentric millionaire widow of a railroad tycoon and mother of eleven. Meck, ten years Tchaikovsky’s senior and moonstruck by his music, became his patroness for the next thirteen years. By her own request, the two never formally met — yet through their constant written correspondence, they developed a strong bond.

The Valse-Scherzo in C major, Op. 34, was completed in this consequential year. Tchaikovsky dedicated the score to violinist Iosif Kotek: his former composition student; the intermediary in his initial correspondence with Meck; and, for a time, likely his lover. Tchaikovsky confided to Modest, “When he caresses me with his hand, when he lies with his head inclined on my breast, and I run my hand through his hair and secretly kiss it … passion rages within me with such unimaginable strength.”

The delicately scored Valse-Scherzo combines forms emblematic of distinct eras. Tchaikovsky infuses the old-world salon elegance of the waltz with the more modern scherzo’s devilish mischief, churned by impish repeated notes and fiendish double-stops in the solo part. Like the Sérénade before it, this modestly scaled score would not be out of place as the inner movement of a larger concerto. (A cadenza even appears, bridging the work’s soulful middle section to the reprise of the opening.)

Such was the origin of Souvenir d’un lieu cher, Op. 42. Over the course of three days in March 1878, Tchaikovsky wrote a Méditation in D minor, originally intended as the slow movement of his Violin Concerto but quickly discarded. He returned to the work in May, now envisioning it as the first movement of a three-movement work for violin and piano. On May 25, Tchaikovsky traveled to Brailov, Meck’s estate where he was welcomed at a guesthouse (so long as their agreement to avoid personal contact remained in effect; during one stay, while the composer was out for a walk and Meck was running late for a social appointment, the two inadvertently came face to face for the only time). His retreat to Brailov provided much-needed catharsis in the wake of the marriage crisis, which, in addition to the psychological trauma it caused, had moreover halted Tchaikovsky’s creativity.

At Brailov, rejuvenated, he added a Scherzo and Mélodie to the Méditation. The resultant Souvenir d’un lieu cher — “memory of a beloved place” — bears an enigmatic dedication to “B******.” The dedicatee is Brailov itself; Tchaikovsky made a gift of his manuscript to Meck. Glazunov later orchestrated the Scherzo and Mélodie to prepare an arrangement of Souvenir d’un lieu cher for violin and orchestra, in which incarnation it is commonly heard.

The Méditation opens with an introduction of searching poignancy. The music is set in D minor, but chromatic turns and sighing appoggiaturas shroud the harmony in an enigmatic haze. The music settles unequivocally into somber D minor as the violin enters, issuing the melancholic theme. A second theme appears in B-flat major, graceful and elegant. Tchaikovsky marks the accompaniment dolce as the violin takes a fanciful turn, marked by dancing triplets and decorative trills. Although the music’s character has changed, a sense of nostalgia continues to permeate the movement. As the Méditation approaches its close, the violin shows flashes of virtuosity, reflecting Tchaikovsky’s original intention for the work.

The remainder of Souvenir echoes Mendelssohn. The blistering Scherzo recalls that composer’s signature Midsummer Night’s Dream scherzo, just as the concluding Mélodie evokes his Lieder ohne Worte; indeed, Tchaikovsky alternately described this movement as a “chant sans paroles.” It likewise harkens back to Schubert in its uncannily expressive melodic sensibility. Particularly in its lighthearted grazioso scherzando moments, this delightful finale strongly suggests the composer’s fond appreciation of his benefactress’s hospitality.

The jewel among Tchaikovsky’s music for violin and orchestra, the Violin Concerto in D Major, Op. 35, is also one of his most rapturous creations. Its composition was contemporaneous with that of Souvenir: Tchaikovsky completed the Concerto in an astonishing twenty-five days over March and April of 1878. Kotek served as muse to the composer, offering instrumental insights and feedback. “How lovingly he’s busying himself with my concerto!” Tchaikovsky wrote to his brother Anatoly. “It goes without saying that I would have been able to do nothing without him. He plays it marvelously.” The same anxiety over whispers about his sexuality that drove Tchaikovsky to marry likely precluded the Concerto’s dedication to Kotek.

With Auer demurring to play it, the Concerto received its premiere only three years later, in Vienna, conducted by Hans Richter, with Brodsky as soloist. The Concerto fared poorly among Viennese audiences (who were generally hostile to new music) and was infamously derided by Eduard Hanslick as “long and pretentious … [The Concerto] brought us face to face with the revolting thought that music can exist which stinks to the ear.” Its enormous popularity over the following century and into the present day have, of course, overruled Hanslick and vindicated Tchaikovsky. Straightforward in form, the Concerto holds tremendous appeal for its melodic content and virtuosic flair.

The work betrays a debt to Édouard Lalo, whose Symphonie espagnole Kotek and Tchaikovsky played together in an arrangement for violin and piano around the time of the Concerto’s composition. Tchaikovsky praised the Symphonie to Meck in terms that would equally well describe his forthcoming score: “It has a lot of freshness, lightness, of piquant rhythms, of beautiful and excellently harmonized melodies. … [Lalo] does not strive after profundity, but he carefully avoids routine, seeks out new forms, and thinks more about musical beauty than about observing established traditions.”

The opening Allegro moderato’s pleasing melodic character suggests Tchaikovsky’s contentment in Kotek’s company with the anguish of his marriage to Milyukova behind him. The unforgettable tune with which the soloist first enters is initially one of easy gracefulness; this is steadily transfigured by means of dazzling virtuoso writing into an expression of euphoric ecstasy. As in Souvenir d’un lieu cher, Tchaikovsky recalls Mendelssohn, placing the cadenza before the movement’s recapitulation, as Mendelssohn does in his own violin concerto.

The integration of Western models and his own Russian cultural identity was an aesthetic balancing act throughout Tchaikovsky’s career. While the Concerto’s first movement relates strongly to the German Romantic tradition, the composer’s mother tongue permeates the second and third. The Canzonetta begins as a hymn suffused with Slavic harmonies, soon giving way to the violin’s plaintive melody. The rollicking rondo finale answers the mournful Canzonetta with an irresistible folk dynamism, the soloist firing a steady fusillade of gypsy pyrotechnics. Noteworthy here is a tender episode, introduced as a duet between oboe and clarinet and redolent of Tatyana in Tchaikovsky’s opera Eugene Onegin — a fleeting but earnest moment of introspection before the Concerto races to its exultant conclusion.

© 2016 Patrick Castillo

Patrick Castillo leads a multifaceted career as a composer, performer, writer, and educator.

Album Details

TT: 74:20

Producer: Judith Sherman

Session Engineer: Viggo Mangor

Post-production Engineer: Bill Maylone

Editing Assistance: Jeane Velonis

Recorded: September 14—17, 2015, in the Odense Concert House’s Carl Nielsen Hall, Odense, Denmark

Photos of Jennifer Koh: Jürgen Frank

Graphic Design: Nancy Bieschke

© 2016 Cedille Records

CDR 90000 166