Store

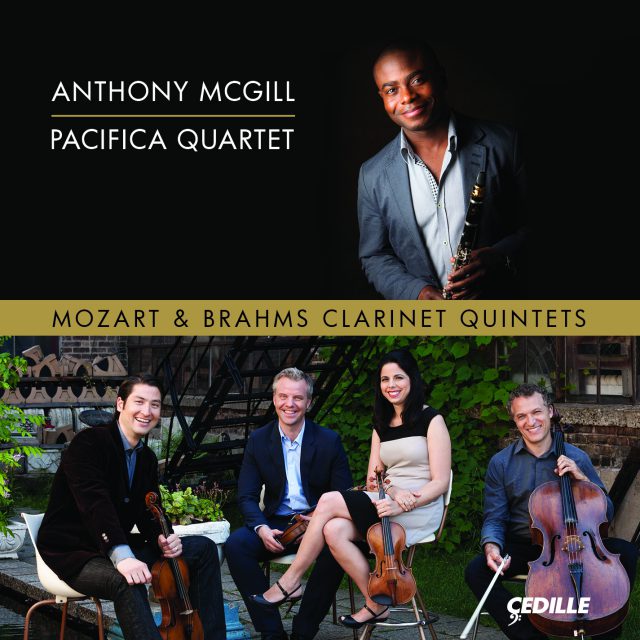

The dynamic, Grammy Award-winning Pacifica Quartet and the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra’s superstar principal clarinetist Anthony McGill join forces for the clarinet quintets of Mozart and Brahms — widely considered the greatest chamber works for this combination of instruments.

Mozart’s radiant Clarinet Quintet in A major, K. 581, with its aria-like melodies, and Brahms’s expansive Clarinet Quintet in B minor, Op. 115, with its haunting, sunset glow, are mature masterworks inspired by phenomenal clarinetists of the day.

Preview Excerpts

WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART (1756–1791)

Quintet in A major for Clarinet and Strings, K. 581

JOHANNES BRAHMS (1833–1897)

Quintet in B minor for Clarinet and Strings, Op. 115

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletMozart and Brahms Clarinet Quintets

Notes by Andrea Lamoreaux

Anton Paul Stadler (1753–1812) and his brother Johann were both clarinetists with the Vienna Music Society in the 1770s, and were also employed as musicians in the household of Count Dmitry Golitsin, Russian ambassador to the Viennese imperial court. In the early 1780s, Emperor Joseph II organized his own wind band — oboes, clarinets, bassoons, and horns — and the Stadlers became part of this group, known in 18th-century Germany and Austria as a Harmonie. By the time they became the first official clarinet players in the imperial court orchestra, Anton Stadler had already met a talented Viennese newcomer whose reputation as both composer and performer had preceded his arrival from his native city of Salzburg: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.

Stadler organized the 1784 concert at which Mozart’s grand Wind Serenade (Gran Partita) was premiered, and also participated in the first performance of the composer’s Quintet for Piano and Winds (K. 361 and K. 452, respectively). Later he’d be the inspiration for the Kegelstatt Trio for Clarinet, Viola, and Piano (K. 498) and Mozart’s last completed instrumental composition, the Clarinet Concerto K. 622. Stadler first played the concerto in Prague, where he was in the opera orchestra for La Clemenza di Tito, whose score features clarinet prominently.

During the 1790s Stadler toured Russia, Germany, and the Baltic states as a concert soloist while continuing his role in the imperial court orchestra. He retired as a performer around the year 1800 but continued to teach.

The Serenade, Piano and Wind Quintet, Concerto, and Trio are all marvelous, but it’s the piece Mozart wrote in 1789, calling it Stadler’s Quintet, that immortalized this great woodwind artist’s name. The A Major Quintet for Clarinet and Strings can be heard as a musical manifestation of friendship, reminding us in every measure how Mozart and Stadler found each other kindred spirits.

They even shared a joint attraction to the Freemasonry movement, with its promise of universal brotherhood and enlightenment. Both were members of the Viennese Masonic lodge called New Crowned Hope.

This is one of Mozart’s best-known chamber compositions and a special favorite for the sheer beauty of its themes and skillful interplay among the five instruments. Mozart was an outstanding composer of concertos, and the Quintet has the sound of a mini-concerto at times when the clarinet comes to the fore. For the most part, however, it’s pure chamber-music with equal partners.

The serenity and sunlit good cheer of the entire piece is heralded right at the beginning by the strings’ gently harmonious opening theme. The clarinet joins in almost immediately with a comment that starts in its mellow low register and rises to its bright higher one. As the sonata-form movement unfolds, the first violin and cello have important solo passages along with the clarinet. In the exposition, three distinct themes are presented. The short development mostly features the string players; the recapitulation brings the original themes back in elaborated form.

The Larghetto movement has been compared to a Nocturne or Romance — terms that came along in the 19th-century’s Romantic era (and are perhaps unsuited to describing a Classical-era quintet). Another comparison that’s sometimes made is to an operatic aria, which feels more relevant, given Mozart’s mastery of that realm. It’s less an aria than a duet, however, because the movement is dominated by a lyrical dialogue between the clarinet and the first violin. Muted strings add an aura of enchantment and distant beauty.

In the elegant Menuetto, inward-turning emotion gives way to extroverted conversation, led by the clarinet. The movement contains two contrasting Trio sections, the first for strings alone, the second a dancing duet for clarinet and violin. To conclude the Quintet, Mozart presents a cheerful theme with five variations and a coda. Contrasts of tempo and a brief excursion into the minor mode enliven the sequence of variations, with the viola given prominence in Variation 3. Throughout this finale, the clarinet takes the lead and, as in a concerto, is given a short solo cadenza. The coda brings all five players together in happy harmony.

Richard Mühlfeld (1856–1907) joined Germany’s Meiningen Court Orchestra as a violinist, but soon switched over to his second instrument, the clarinet, on which he was largely self-taught. In addition to his work for Meiningen, which was closely associated with Brahms’s music, Mühlfeld spent several summers as clarinetist for the Bayreuth Festival Orchestra playing Wagner’s operas. Brahms was first captivated by Mühlfeld’s artistry at a Meiningen concert in March 1891, not long after Brahms told his publisher that he was going to retire from composing. It can be debated whether he really meant that, but hearing Mühlfeld certainly fired Brahms up to return to his craft. In summer 1891, he wrote a Clarinet Trio with cello and piano and a Clarinet Quintet with four strings. Three years later, he produced a pair of sonatas for clarinet and piano that he also transcribed for viola and piano. (His canon of final works is rounded out by the Four Serious Songs and a set of 11 chorale-preludes for organ.)

Mühlfeld premiered the Clarinet Quintet in Meiningen in fall 1891 with the string quartet headed by Brahms’s violinist friend, Joseph Joachim. Joachim would later introduce both the Trio and the Quintet at concerts in Berlin.

Similarities (beyond instrumentation) between Brahms’s Op. 115 and Mozart’s K. 581 include their use of muted strings in the slow movements and finales laid out in theme-and-variations form. Yet the tone of the two works is quite different. Predominantly in a minor key, the Brahms is more flavored with melancholy, more passionate, even a little portentous at times. Its first two movements are lengthy, the last two shorter and more direct. There’s a remarkable sense of thematic unity, as Brahms ingeniously transforms and expands his opening idea to generate themes heard later.

The Quintet is often described as “autumnal” — perhaps because, as one of the composer’s last works, it comes from the autumn of his life. But it’s certainly not a sad piece: vigorous and intense, it has a variety of moods and reveals a musical genius still reveling in showcasing his skills.

The Allegro finds the clarinet and violins first in D major, the relative of B minor; this home key is eventually established by the cello’s opening theme. Since the two main themes of this movement are closely related, it can be heard as variations as well as a standard sonata form of exposition–development–recapitulation. In the emotionally intense Adagio, dreamy and distant opening and closing sections surround an agitated central portion that’s been linked to Brahms’s lifelong fondness for the improvisatory style of Hungarian gypsy music. The most prominent voice in the Adagio is the clarinet.

The third movement takes its time reaching the expected Scherzo tempo. It opens Andantino with the clarinet playing in D major, joined by the viola and cello. Then the Scherzo proper finds the strings playing a related theme, but in B minor. In the finale, a passionate, dark-hued theme is varied with the clarinet partnering each string player in turn. The strongly rhythmic second variation is once more reminiscent of the Hungarian style. A variation in which the viola takes a leading voice progresses to a repeat of the Quintet’s opening theme. This leads to the coda and a powerful final chord.

Andrea Lamoreaux is Music Director of 98.7wfmt, Chicago’s Classical Experience

Album Details

Total Time: 68:38

Producer/Engineer: Judith Sherman

Editing: Bill Maylone

Editing Assistance Jeanne Velonis

Recorded:

Brahms: August 30 & 31, 2013; Auer Hall, Indiana University

Mozart: September 9 &10, 2013; The Performing Arts Center

Purchase College, State University of New York

Front Cover Design: Luis Ibarra

Inside Booklet & Inlay Card Design: Nancy Bieschke

Photography Pacifica Quartet: Saverio Truglia

Anthony McGill: David Finlayson

Funded in part by a grant from Elizabeth F. Cheney Foundation.

© 2014 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 147