Store

A Personal Note from Rachel Barton Pine

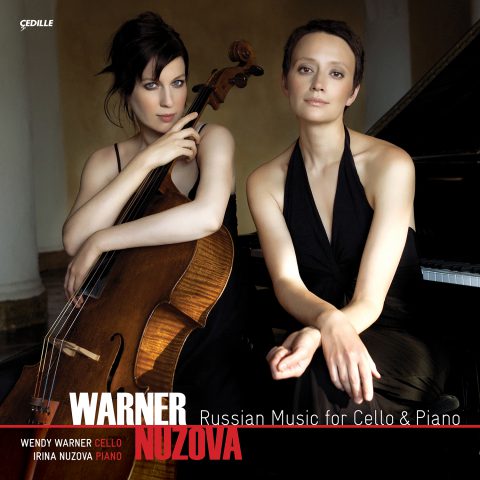

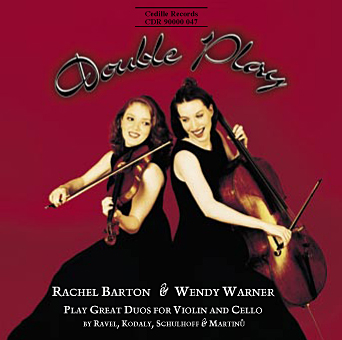

Wendy Warner and I began playing chamber music together in 1985 at the Music Institute of Chicago (formerly the Music Center of the North Shore) when I was 10 and she was 12. From the beginning, we enjoyed rehearsing and performing together. We quickly became fast friends and continued to play in string quartets until the end of high school. In 1988, our group, the Diller String Quartet, won first prize in the Junior Division of the Fischoff National Chamber Music Competition. The two of us had as much fun jamming on the last movement of the Prokofiev Quartet No. 2 as we had acting silly at our hotel afterwards.

After high school, Wendy went off to Curtis (in Philadelphia) and eventually settled in New York City. As each of us participated in international competitions and launched solo careers, we always kept in touch. We were reunited in 1996 to perform the Brahms Double at the Grant Park Music Festival in Chicago. While each of us had grown musically over the years, playing together was so natural that it seemed as though we had never spent the time apart.

That performance inspired us to assemble a program of duos for violin and cello. The Ravel and Kodaly, two of the most famous compositions for this combination of instruments, were obvious choices. After reading both of Martinu’s Duos, we agreed that No. 2 was so energetic and optimistic that we had to include it. Wendy introduced me to composer Erwin Schulhoff, and I became a fan immediately. His Duo for violin and cello had been recorded with others of his works, but never with other violin/cello compositions. We were very excited about presenting it among the more famous works in this genre, as it more than holds its own.

It’s a great pleasure to share with you this joyful collaboration with one of my best friends and favorite musicians.

Preview Excerpts

BOHUSLAV MARTINU (1890-1959)

Duo No. 2

ERWIN SCHULHOFF (1894-1942)

Duo

MAURICE RAVEL (1875-1937)

Sonata

ZOLTAN KODALY (1882-1967)

Duo, Op. 7

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletDouble Play - Duos for Violin and Cello

Notes by Todd E. Sullivan

The violin and cello have enjoyed a relatively limited musical partnership over the past two centuries. Duo literature specifically geared toward the amateur salon-music audience proliferated during the Classical and early-Romantic periods. Some composers wrote specifically for violin and cello, focusing on the string members of the then-defunct Baroque solo sonata grouping. Music publishers seeking the largest possible clientele also issued scores in flexible instrumentation with violin and cello as one option. By contrast, the twentieth century has seen a surge of violin and cello duo writing for professional musicians. Composers have responded less to market demand than personal circumstances, such as collaborations between colleagues, a poignant or tragic moment in time, or just the sheer intimacy of the duo grouping.

A native of Poliãka, Bohemia, Bohuslav Martinu (1890-1959) lived most of his adult life – thirty-six years – outside his homeland, first in Paris, then the United States, and finally back in western Europe. In October 1957, the composer and his wife Charlotte were once again on the move. MartinÛ, having just completed a consulting professorship at the American Academy of Music in Rome, sought a quiet place to complete his opera The Greek Passion, based on Nikos Kazantsakis’ novel, Christ Crucified. The couple traveled to Paris for two weeks, visited their former villa on Mont Boron (near Nice), and eventually settled in Switzerland.

The Martinus enjoyed the generous hospitality of Maja and Paul Sacher, the Swiss conductor, at their Schönenberg Estate in Pratteln. Charlotte recalled, “We lived there surrounded by nature, in great stillness, in a comfortable apartment, warmed by the deep friendship of the Sachers.” Martinu needed this support and peace more than ever: painful inflammation in his hands made writing nearly impossible, or at least illegible, a situation relieved slightly by electric therapy. Less hopeful, though, was his other infirmity, an incurable case of stomach cancer diagnosed during surgery for a suspected ulcer on November 7, 1958. Martinu died nine months later on August 28, 1959.

The Duo No. 2 for Violin and Cello quickly emerged over a four-day period at Schönenberg, June 28-July 1, 1958. Swiss musicologist Ernst Mohr commissioned this work to honor the fiftieth birthday of his wife, Trauti Mohr. Martinu did not live to hear his duo performed: violinist Hansheinz Schneeberger and cellist Dieter Stehelin gave the first private reading in Basel on March 4, 1962 and the public premiere in the spring of 1963.

Martinu sustains high energy throughout his Allegretto by contrasting metrically ambiguous duo writing with short, lilting, and often very French-sounding chordal segments. The two string partners merge as one voice in the Adagio’s initial phrases, although the cello deferentially moves its chord accompaniment into the background for the violin’s contrasting theme. In the Poco allegro, a Bartókian spirit pervades the wild refrain theme, with its bariolage (a bowing effect involving rapid shifting between strings) and tight wavering around a single pitch.

The Czech-born composer and pianist Erwin Schulhoff (1894-1942) received early musical encouragement from Antonín Dvorák. On his advice, the ten-year-old Erwin entered the Prague Conservatory. He later studied in Vienna, Leipzig (with Max Reger), and Cologne. Other important musical influences of his youth included Richard Strauss, Claude Debussy (with whom Schulhoff had private lessons in Paris), and members of the modern Russian school: Mily Balakirev, Anatoly Liadov, and Alexander Scriabin. At age seventeen, Schulhoff won Leipzig’s Mendelssohn Prize for piano and, five years later, for composition.

Four years of military service during World War I changed the direction of Schulhoff’s life. But action on the Russian and Italian fronts did not prevent Schulhoff from composing – even as he battled to save his hands from frostbite in Russia. He emerged from combat with a sizeable body of new works. After the war, he remained in Germany, cultivated an association with the avant-garde Dadaist movement, and became heavily influenced by jazz. Arnold Schoenberg’s expressionist techniques and the neo-Classical idiom of Igor Stravinsky also informed his broadening, eclectic style.

Schulhoff returned to Prague in 1923 to teach private piano lessons, and instrumentation and score-reading at the conservatory. His compositions during this period display the growing influence of Czech folk music. He also found a direct source of inspiration in fellow countryman, Leos Janácek. Schulhoff knew several of Janácek’s works, in particular the opera Jenufa, which he had prepared as répétiteur for a 1918 performance in Cologne. Then, in 1924, he published an article in Anbruch commemorating Janácek’s seventieth birthday; the master, in turn, later expressed his deep gratitude to “my dear friend.”

The Duo for Violin and Cello – composed between February 2 and 5, 1925 (the revised score is dated November 11, 1925) and dedicated to “Mr. Leos Janácek in deep admiration” – illustrates Schulhoff’s persuasive merger of folk and contemporary elements. Its initial pentatonic counterpoint quickly “modernizes” with the free introduction of chromatic pitches. Schulhoff recycles this material in later movements as a means of integrating the entire work. For example, the finale begins with a compressed version of this opening duo. The five-beat meter and complex rhythmic subdivisions of the opening Moderato are characteristic of many Central European folk music traditions. As the movement progresses, modern string effects such as left-hand pizzicatos and artificial harmonics appear. The Zingaresca sizzles with fiery Hungarian fiddle playing. Schulhoff at times seems to imitate Janáãek’s technique of rotating variations of simple melodic cells, as in the Andantino movement and the finale’s Presto fanatico conclusion. Stanislav Novák and Maurits Frank gave the world premiere in Prague on October 30, 1925.

An avowed communist, Schulhoff considered relocating his family to the Soviet Union in 1939, after the signing of the Munich Agreement and Hitler’s seizure of Czechoslovakia. He took Soviet citizenship in 1941, but his efforts to avoid the Nazis failed. Schulhoff, a Czech Jew now associated with an enemy nation, was captured and imprisoned in the Wälzburg concentration camp, where he died from tuberculosis on August 18, 1942.

For a commemorative issue of La Revue Musicale (December 1, 1920), editor and musicologist Henri Prunière commissioned several works in memory of Claude Debussy, who had died two years earlier. The musical contributors were all of international caliber: Béla Bartók, Paul Dukas, Manuel de Falla, Eugene Goossens, Gian Francesco Malipiero, Albert Roussel, Erik Satie, Florent Schmitt, and Igor Stravinsky. Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) offered a single-movement memorial composition for violin and cello.

During the summer of 1921, Ravel returned to his violin and cello score while vacationing in the Basque region. These comfortable ancestral surroundings – his mother was Basque – inspired a more colorful vision of the music: Ravel’s friend and biographer Roland-Manuel (pseudonym of Alexis Manuel Lévy) reported that the composer commenced the Lent in black and blue pencil and changed to poppy yellow in the middle. The original commemorative piece took its place as the first movement of this large-scale sonata. The project proved troublesome for Ravel: “This rascal of a duo makes me extremely ill,” he reported in September 1921. On January 30, 1922, he wrote to music critic Michel-Dimitri Calvocoressi expressing dissatisfaction with the scherzo. Ravel threw out the movement, immediately began its replacement, and completed the four-movement score in February.

The difficulty of composing for this sparse two-instrument texture ultimately diverted Ravel into new stylistic territory, marked by a contrapuntal orientation and concise Classical structures, very near Debussy’s later music. Ravel understood this work’s significance to his creative development: “I believe this sonata marks a turning point in the evolution of my career. In it, thinness of texture is pushed to the extreme. Harmonic charm is renounced, coupled with an increasingly conspicuous reaction in favor of melody.” He did not easily recover from the experience, however, and produced only one minor work over the next two years.

In the opening Allegro, the violin repeats a bimodal pattern, alternating A-minor and A-major arpeggios, in quasi-ostinato fashion. This basic idea, though transformed in character, reappears in the three remaining movements: the scherzo’s pizzicatos constantly shift between C-natural and C-sharp (in the context of “A” chords); these motives are rearranged to create the slow movement’s canonic theme; and the finale juxtaposes several new ideas with first-movement motives. Ravel occasionally extends half-step relationships to a tonal level, such as the bitonal passage in the scherzo that pits B major against C minor.

Arbie Orenstein observed that the final two movements convey a Hungarian quality in their “folk flavor” and “driving and harsh dissonances.” Ravel evidently knew Kodály’s duo, written eight years earlier; his original title (“Duo”) made the connection more apparent. The direction of influence might not be so clear cut, however. In a 1918 memorial tribute to Debussy, Bartók commented that “It was of great interest to us Hungarians that we could see the influence of eastern European folksong in Debussy’s melodies; certain pentatonic progressions were noticeable such as are found in the ancient Hungarian melodies, especially those in the Székely region.” So Ravel may have absorbed these qualities indirectly, through his deceased countryman.

Violinist Hélène Jourdan-Morhange, who played the sonata’s world premiere with Maurice Maréchal at a Société Musicale Indépendante concert at the Salle Pleyel on April 6, 1922, recalled the precise ensemble coordination Ravel demanded of his performers. The scherzo movement required countless repetitions (“The cellist and I went over it again and again till we were giddy”) to ensure uniform spiccatos in the two string instruments. Jourdan-Morhange protested: “‘It’s complicated,’ I said, in order to keep my end up. ‘The cello has to sound like a flute and the violin like a drum. It must be fun writing such difficult stuff but no one’s going to play it except virtuosos.’ ‘Good!’ he said, with a smile, ‘then I shan’t be assassinated by amateurs!'”

Zoltán Kodály (1882-1967), the Hungarian composer, pedagogue, and ethnomusicologist, composed his Duo for Violin and Cello, Op. 7 in 1914. Imre Waldbauer and Jenö Kerpely gave the first performance in Budapest on May 7, 1918. Kodály owed a considerable debt to these two artists, who individually and as members of the Waldbauer Quartet promoted his works both at home and abroad. Non-Hungarian audiences first encountered Kodály’s music at the Festival Hongrois in Paris (March 1910; Kerpely and Béla Bartók performed the Sonatina for Cello and Piano on March 17) and the International Congress of Musicians in Rome (April 1911). The lively aesthetic debate and controversy sparked by these performances enhanced Kodály’s international reputation. Bartók, who with his compatriot became known as the “young barbarians” from Hungary, reported after the Paris festival that “Kodály had an enormous success. The effect of his program was quite sensational, for here was a man emerging from complete obscurity to become one of the foremost composers.”

The early 1910s witnessed Kodály’s rise to prominence in other musical avenues as well. He and Bartók laid plans to establish the New Hungarian Music Association with its own orchestra and journal, but the idea never reached fruition. They collaborated on an ambitious folksong project – the accumulation of more than 3,000 melodies collected in Transylvania – and, in 1913, pitched their Plan for a New Universal Collection of Folk Songs to the Kisfaludy Society, which politely declined. Kodály again ventured into the countryside to record peasant songs among the Székely people of Bucovina in 1914. He also taught composition at the Budapest Academy of Music, which awarded him full tenure in 1912.

Kodály’s dual professional interests as a music ethnographer and teacher ultimately coalesced in a vision for the future regeneration of Hungarian music, beginning with the reform of music education in elementary school. “The foundations of a genuinely national musical consciousness have to be unearthed from beneath the accumulated rubble of Hungarian indifference and a misconceived and outmoded method of training . . . Our movement rejects all distinctions based on class or social status. Music belongs to all.” His populist, folk-based approach provided a model for educational systems worldwide.

The Duo for Violin and Cello, Op. 7 models perfectly the cross-pollination of Hungarian folk materials and the formal structures of art music. Its opening pentatonic melody falls into the Dorian mode, while a contrasting theme, alternating melodic phrases and pizzicato accompaniment, sounds Aeolian. Intensely heartfelt lyricism, which occasionally bursts forth in deep torment, courses through the Adagio. The middle section employs a “trio” texture: the cello provides the bowed soprano melody and a plucked bass accompaniment, while the violin spins an active countermelody in the alto range. Kodály’s Magyar-styled finale simulates the radical tempo changes of the verbunkos (recruiting dance) style with its exciting alternation of slow (friss) and rapid (lassu) sections.

– © Todd E. Sullivan 1999

Todd E. Sullivan is Assistant Professor of Music (musicology) at Indiana State University and is program annotator for the Ravinia Festival.

About the Instruments

Rachel Barton plays the ex-Lobkowicz Antonius & Hieronymous Amati of Cremona, 1617, on generous loan from her patron.

The Seal of the Lobkowicz Family on the back of the violin identifies it as one of the instruments held by this illustrious European family. Prince Lobkowicz was a significant patron of Beethoven.

The Amati family is responsible for the violin as we know it today. Andreas Amati invented the violin c. 1550. His sons Antonius and Hieronymous, known as the Brothers Amati, brought violin making forward into the 17th century. Hieronymous’s son Nicolo continued to nearly the end of the 17th century and was the teacher of Andreas Guarneri and Antonio Stradivari.

The violin Miss Barton plays is a particularly fine example of the makers’ work and is excellently preserved. The top is formed from two pieces of spruce showing fine grain broadening toward the flanks. The back is formed from two pieces of semi-slab cut maple with narrow curl ascending slightly from left to right. The ribs and the original scroll are of similar stock. The varnish is golden-brown in color.

For this recording, Wendy Warner performed on a 1707 Joseph Filius Andreas Guarneri, courtesy of Morel & Gradoux-Matt, Inc.

Album Details

Total Time: 72:40

Recorded: December 1-4, 9, 10, 1998 at WFMT Chicago

Producer: James Ginsburg

Engineer: Bill Maylone

Cover: Nesha & Kumiko Fotodesign

Design: Cheryl A Boncuore

Notes: Todd E. Sullivan

© 1999 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 047