Store

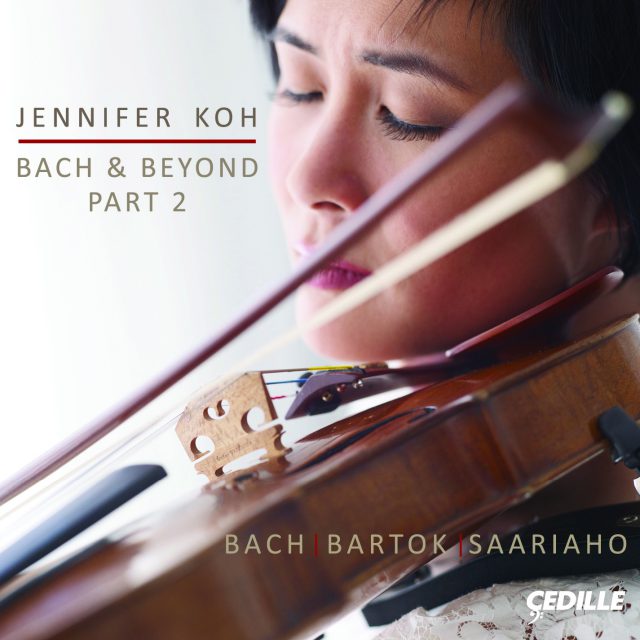

Violinist Jennifer Koh’s Bach & Beyond Part 2 is the newest installment in a three-CD cycle based on her groundbreaking, multiyear recital series of the same name. Koh, “a masterly Bach interpreter and a champion of contemporary repertory” (The New York Times), performs J. S. Bach’s landmark violin Sonatas and Partitas alongside 20th and 21st century solo violin works they’ve inspired, including new commissions.

Bach & Beyond Part 2 offers J.S. Bach’s expressive Sonata No. 1 and contemplative Partita No. 1 for solo violin, Bela Bartok’s lyrical Sonata for Solo Violin, and the world premiere recording of Finnish composer Kaija Saariaho’s alluring, otherworldly Frises for violin and electronics.

Preview Excerpts

J.S. BACH (1685–1750)

Sonata No. 1 in G minor, BWV 1001

BELA BARTOK (1881-1945)

Sonata for Solo Violin Sz. 117, BB 124

Artists

Program Notes

Download Album BookletBach and Beyond Part 2

Notes by Patrick Castillo

Jennifer Koh: Bach and Beyond (Part 2)

Notes by Patrick Castillo

“Once he had heard a particular theme,” read Johann Sebastian Bach’s Obituary, “he could grasp, as it were instantaneously, almost anything artistic that could be brought forth from it.” This assessment of Bach’s fugal writing, in which a brief melodic subject holds the key to a majestic musical creation, may equally well testify to the brilliant conception of the Sonatas and Partitas for Solo Violin. These works, as lyrical as they are virtuosic, demonstrate the same godlike powers of creation by which such fantastical musical realms as The Art of Fugue and The Musical Offering flourish from within extreme constraints. Fueled by what the Obituary identified as his “desire to try every possible artistry,” Bach defies the seeming limitations of writing for violin alone without harmonic accompaniment. From a single melodic instrument, he fashions polyphony and counterpoint, conjures a kaleidoscopic array of characters and textures, and honors numerous formal traditions (church sonatas, dance forms, and, yes, fugue), but reimagines them with such extraordinary vision that these works sound today irrepressibly fresh. Extrapolating Bach’s guiding principle of “all from one and all in one” to the broader historical plane: just as one instrument inspired such a wealth of musical ideas, and just as from an innocuous subject is borne a dizzying fugue, Bach’s Sonatas and Partitas have continued to serve as a definitive point of reference for the violin’s solo repertoire across more than two and a half centuries.

Béla Bartók’s Sonata for Solo Violin, one of the composer’s final works, pays explicit homage to the Baroque master. Bartók composed the Sonata in 1944 for Yehudi Menuhin, after hearing Menuhin perform Bach’s Sonata no. 3 in C Major. Bach’s specter haunts Bartók’s Sonata throughout its four movements, beginning in Tempo di ciaccona—a nod to the monumental Chaconne from Bach’s Partita no. 2 in d minor (see Bach and Beyond Part 1). A rigorous four-voiced fugue follows; Bartók’s craftsmanship channels the complexity of Bach’s counterpoint in a modern voice, as when the fugue’s theme and its inversion appear simultaneously.

The Sonata demonstrates an intense focus on melody—appropriate, after all, to the medium of solo violin, and moreover placing it alongside the Concerto for Orchestra and Third Piano Concerto, both completed in the year following the Sonata and likewise distinguished by their melodic immediacy. This sensibility is especially distilled in the Sonata’s third movement Melodia: a poignant, lyrical utterance, as nuanced in timbre and character as it is plainly spoken. Bartók expands the Sonata’s expressive palette further in the Presto finale, utilizing quarter-tone writing for extended passages. (The composer’s semitone alternatives appeared in Menuhin’s posthumous edition; Jennifer Koh performs Bartók’s original version on this recording.)

Johannes Brahms regarded the aforementioned Chaconne of Bach “one of the most wonderful, incomprehensible works of music. On one staff, for one small instrument, this man has written a whole world of profoundest thought and deepest feelings.” Indeed, Bartók aspires to no less in this wide-ranging Sonata.

Finnish composer Kaija Saariaho’s Frises likewise acknowledges Bach’s Chaconne: the work was composed in 2011 at the request of violinist Richard Schmoucler for a work to follow the Chaconne. As with the Bartók Sonata, here we encounter the timeless resonance of Bach’s art, now in a distinctly modern context. Using the Chaconne’s final D as its point of departure, Frises launches the listener into an otherworldly soundscape of violin harmonics, electronic bells, and other aural fascinations.

Bach biographer Martin Geck groups the Sonatas and Partitas with the Inventions, Sinfonias, and Well-Tempered Clavier as the Cöthen demonstration cycles: works composed during Bach’s time in Cöthen (where he served as Kapellmeister from 1717 to 1723), designed as explications of compositional—specifically, contrapuntal—technique.

The Sonatas and Partitas are arguably the most miraculous of these, dressed in such modest garb and yet accomplishing so much. The aspirations of these works are far-reaching. They encompass academic (fugal, variation, et al.) and popular (dance) forms; the Partitas, moreover, are multicultural dance suites, featuring the German allemande, the French courante, the Spanish sarabande, etc. But more importantly, in their purely musical qualities, the Sonatas and Partitas reflect a particular worldview, as shaped by Bach’s Lutheran faith: that as the fulfillment of his vocation, his musical creation must reflect the splendor and complexity of God’s creation. “Melody and harmony in one,” writes Geck—“that is the message of the six solos, which constitute as well an encyclopedia of the violin: prelude, fugue, concerto, aria, variation, dance—all are performable on it.”

Here we have music of startling expressive power. The Sonata no. 1 in g minor, the most frequently performed of the six violin solos, is perhaps also the most immediately gripping among them, with its impassioned Adagio introduction prefacing the incisive Fuga. The Siciliana introduces a contrasting humor, all delicacy and grace, answered by the exclamatory moto perpetuo of the Presto finale.

Though an assemblage of dance forms, the Partita no. 1 is a work given more to intellectual stimulation than kinetic. Its key, b minor, lends the Partita a brooding, contemplative air. Its structure, distinct from the other Partitas, comprises four pairs of movements, each a dance form and its double (Bach uses the French term, indicating a variation by means of melodic ornamentation); these four pairs together resemble the four-movement plan of the Sonatas, which are based on the slow-fast-slow-fast sonata da chiesa (church sonata) model. For the player, the Partita’s technical challenges are many, immediately from the series of double-stops at the outset of the Allemande through the devilish Tempo di Borea that concludes the work.

But after such formal observations, the music contained in the Sonatas and Partitas ultimately defies analysis. Intended to demonstrate technical prowess, they do so much more, transporting the listener to unexpected emotional depths—and resonating throughout a rich repertoire tradition, tended by generations of composers. In their strength of character and spectacular imaginative breadth, and in that they appeal equally, and with considerable force, to mind and soul, these ostensibly pedagogical works reveal to us the fullness of Bach’s genius.

—© 2014 Patrick Castillo

Album Details

Total Time: 91:18

Producer and Engineer: Adam Abeshouse

Recorded: Saariaho recorded April 20-21, 2014 at Westchester Studios, NY; Bach recorded June 4-5, June 10-12, 2014 at The Performing Arts Center, Purchase College/SUNY; Bartok recorded July 14-16, 2014 at The Performing Arts Center, Purchase College/SUNY

Cover and Inlay Photography: Jürgen Frank

Booklet & Inlay Card Design: Nancy Bieschke

Publishers:

Saariaho Frises © 2011 Chester Music Ltd.

Bela Bartok Sonata for Solo Violin Sz. 117, BB 124 © 1944 Boosey & Hawkes

Funded in part by a grant from the Elizabeth F. Cheney Foundation

© 2015 Cedille Records/Cedille Chicago

CDR 90000 154